Modtaget via elektronisk post. Der tages forbehold for evt. fejl

Europaudvalget

(Alm. del - bilag 725)

udenrigsministerråd

(Offentligt)

_____________________________________________

MPU, Alm. del - bilag 740 (Løbenr. 10367)

ERU, Alm. del - bilag 219 (Løbenr. 10384)

URU, Alm. del - bilag 180 (Løbenr. 10526)

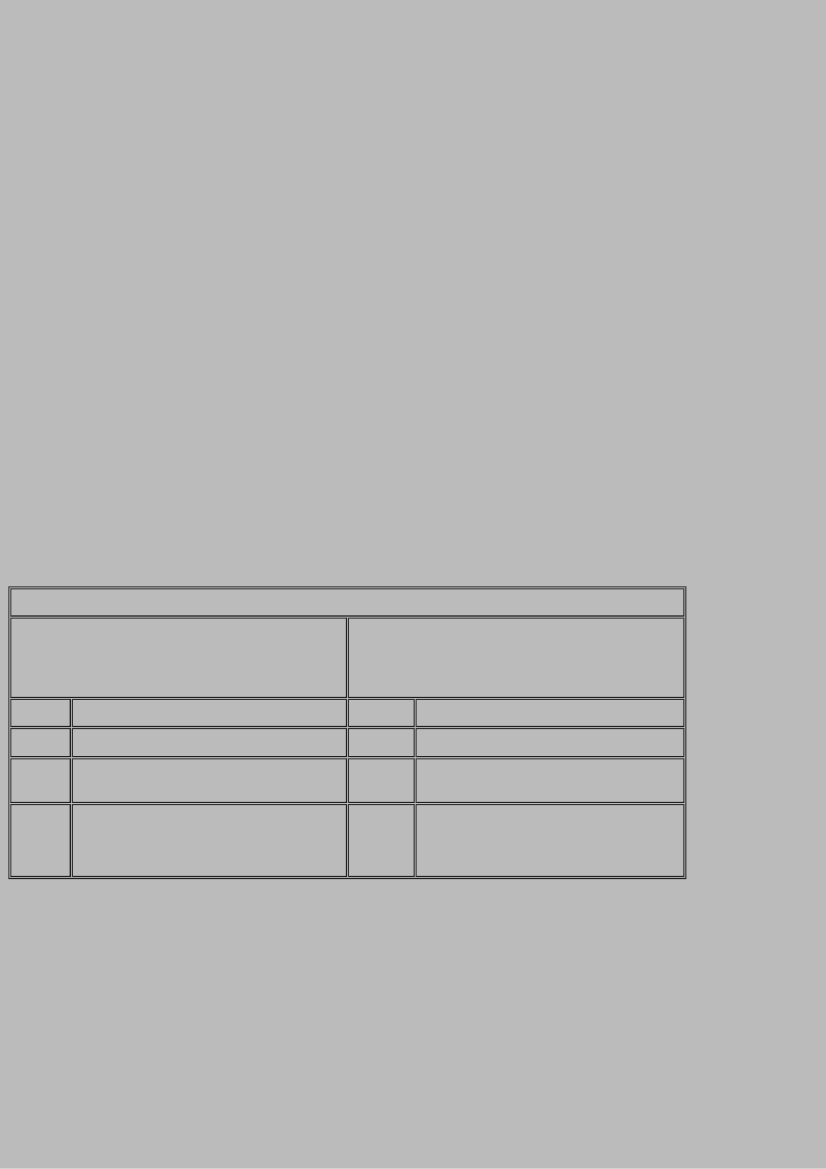

Medlemmerne af Folketingets Europaudvalg

og deres stedfortrædere

Bilag

1

Journalnummer

400.C.2-0

Kontor

EU-sekr.

2. februar 2001

Til underretning for Folketingets Europaudvalg vedlægges Udenrigsministeriets notat vedrørende

diskussionspapir fra Kommissionen om bæredygtig handel.

NOTAT

UDENRIGSMINISTERIET

Nordgruppen

J.nr.:

Bilag:

Fra:

N.4, 97.A.40/7; 97.A.40/8; 97.A.40/30

1

1. februar 2001

Udenrigsministeriet

Dato:

Emne:

Diskussionspapir

Kommissionen om

handel.

fra

bæredygtig

Begrebet "bæredygtig udvikling" er defineret i FN-rapporten "Vor fælles Fremtid" fra 1987. Rapporten, den såkaldte

Brundtland-rapport, blev udarbejdet af en kommission under ledelse af den tidligere norske statsminister Gro Harlem

Brundtland. Ved bæredygtig udvikling forstår rapporten en proces, der tager højde for beskyttelse af miljøet, samtidig med at

den fremmer arbejdstagernes rettigheder og den &os lash;konomiske og sociale udvikling under hensyn til kommende

generationers behov.

Sammenhængen mellem international handel og bæredygtig udvikling er et centralt spørgsmål i bæredygtighedsdebatten.

Handel indvirker på såvel miljøet som arbejdstagernes rettigheder og den økonomiske og sociale udvikling. Handelen skal i

sig selv være bæredygtig, men den kan og bør herudover yde et bidrag til fremme af bæredygtig udvikling

Den tiltagende, internationale opmærksomhed omkring forholdet mellem handel og bæredygtig udvikling kan bl.a. illustreres

af følgende: