Europaudvalget 2009-10

EUU Alm.del Bilag 429

Offentligt

FROM PROTESTTO PRISONIRAN ONE YEAR AFTERTHE ELECTION

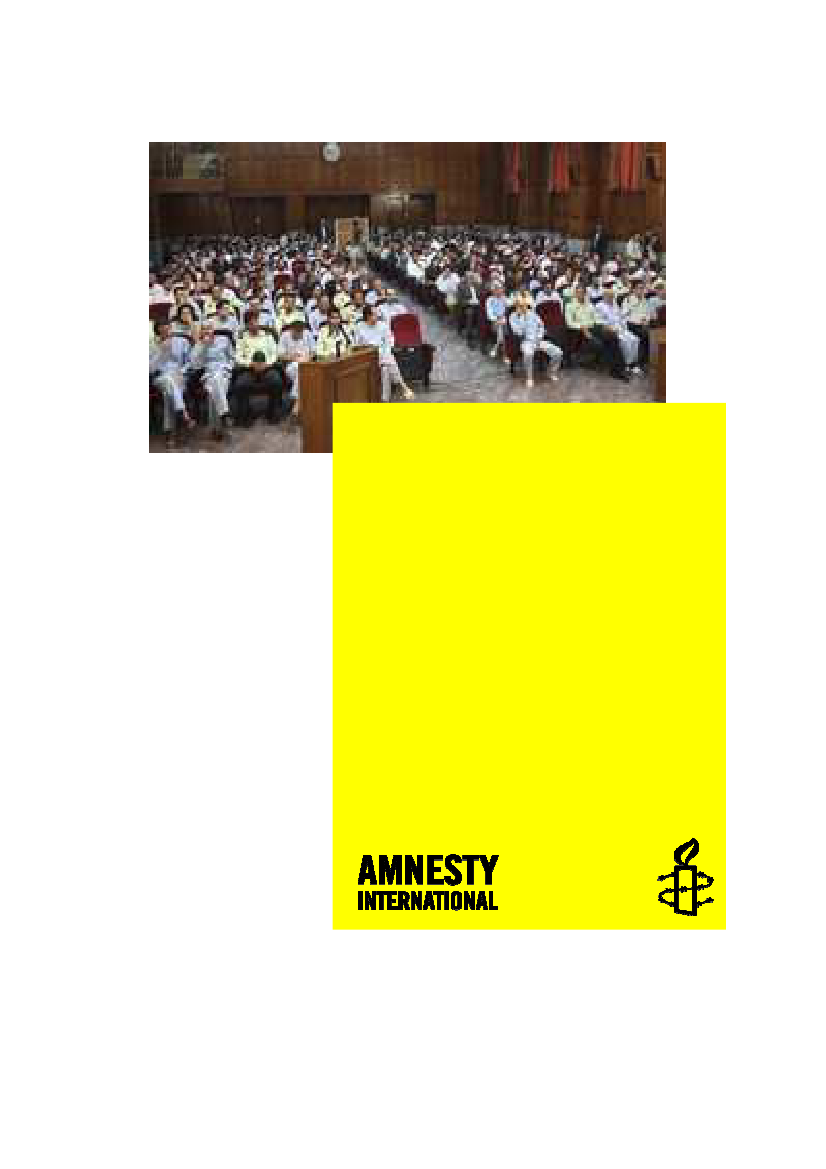

Amnesty International PublicationsFirst published in 2010 byAmnesty International PublicationsInternational SecretariatPeter Benenson House1 Easton StreetLondon WC1X 0DWUnited Kingdomwww.amnesty.org�Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2008Index: MDE 13/062/2010Original Language: EnglishPrinted by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United KingdomAll rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any formor by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of thepublishers.Cover photo: Tehran's Revolutionary Court, 26 August 2009.� ASSOCIATED PRESS

Amnesty International is a global movement of 2.2 millionpeople in more than 150 countries and territories, whocampaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person toenjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration ofHuman Rights and other international human rightsinstruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilizeto end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International isindependent of any government, political ideology, economicinterest or religion. Our work is largely financed bycontributions from our membership and donations

CONTENTS1. Introduction .............................................................................................................52. Who are the prisoners? ..............................................................................................8Political activists .......................................................................................................9Students and graduates............................................................................................10Journalists ..............................................................................................................12Filmmakers and other artists.....................................................................................13Rights defenders .....................................................................................................13Lawyers ..................................................................................................................16Clerics ....................................................................................................................17People linked to members of banned groups...............................................................17Members of ethnic and religious minorities ................................................................18Workers and members of professional bodies ..............................................................20Family members of prominent figures and detainees ...................................................213. Arbitrary arrest and detention ...................................................................................22Detention without charge or trial ...............................................................................24Unacknowledged detention amounting to enforced disappearance ................................25Iran’s detention centres and prisons ..........................................................................26Evin Prison ..........................................................................................................28Access to family members and legal representatives ....................................................304. Torture and ‘confessions’ .........................................................................................33

Rape and other sexual abuse .................................................................................... 35Threats against family members................................................................................ 36Poor prison conditions and denial of medical care ...................................................... 36‘Confessions’ .......................................................................................................... 385. Trials: the final gloss on a system of injustice ............................................................ 40Laws that restrict basic freedoms .............................................................................. 42‘Show trials’ – a travesty of justice ............................................................................ 43Evin Prison’s court .................................................................................................. 44Politically motivated use of the death penalty............................................................. 456. Impact on families.................................................................................................. 487. Impunity................................................................................................................ 508. Life in exile............................................................................................................ 539. Conclusion and Recommendations ........................................................................... 56Endnotes ................................................................................................................... 58

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

5

1. INTRODUCTION“The prisoner’s worst nightmare is the thought ofbeing forgotten.”Maziar Bahari, Iranian-Canadian journalist, after his release from four months of detention in Evin Prison1

One year on from the disputed presidential election of June 2009, Iranians who want tocriticize the Government or protest against mounting human rights violations face an ever-tightening gag as the authorities and the shadowy intelligence services – shaken to the core bythe events which followed – consolidate their grip on the country and intensify the repressionalready in place for years. Iranians have moved from protest to prison, as the authorities resortto locking up hundreds of people in a vain attempt to silence voices peacefully expressing adissenting view to the narrative which the authorities wish to provide of the election and itsaftermath.Thousands of people – over 5,000 according to official statements, although the true figure isalmost certainly higher – have been arrested during mass demonstrations which first eruptedon13 June 2009, the day after the election. Demonstrations took place steadily throughoutJune until mid-July 2009 in spite of the authorities’ determination to quell protests, thencontinued more sporadically on days of national importance, whenever public demonstrationswere permitted.2At the time of writing, demonstrations which took place during the religiousfestival of Ashoura, which fell on 27 December 2009, were the last mass demonstrations tooccur since the election, when over 1,000 people were arrested, according to official figures.Attempts to hold further demonstrations on 11 February 2010, the anniversary of the foundingof the Islamic Republic were prevented by the heavy presence of security forces. Most of thosearrested have been released, although some have returned to prison to begin serving prisonsentences, but may also spend short periods free on “temporary leave”. These “revolving prisondoors” make it difficult to give precise numbers of those held at any one time.Those who demonstrated against the Government were met by security forces wielding batons,using tear gas and sometimes firing live rounds.3Hundreds of others have been arrested attheir homes or workplaces, usually by unidentified plain clothes officials bearing generic arrestwarrants. Some have been detained in conditions amounting to cruel, inhuman and degradingtreatment. Many have been tortured, including by beatings, rape and solitary confinement insmall spaces for long periods. Hundreds have been sentenced after grossly unfair trials tolengthy prison sentences, while many others are still held without charge or trial. Some havebeen sentenced to death.At the same time, the Iranian authorities have passed new laws to restrict people writing onwebsites and established new security bodies to monitor web content. They have criminalizedcontact with over 60 foreign institutions, media organizations and NGOs – a move which canonly be construed as an attempt to isolate Iranians and prevent news, including on humanrights violations, from leaving the country.4They have continued to close down newspapers thatare deemed to cross the ever-shifting “red line” of what they consider to be acceptable.Websites and email services have been filtered or blocked and the police have warned that

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

6

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

SMS messages are monitored.5They have fired many university professors and staff on thegrounds that they do not have sufficient “belief” in the Islamic Republic. Renewed efforts toimplement “morality” codes concerning dress and gender segregation are underway whichparticularly impede women’s ability to function freely in society. They have issued numerousthreatening statements and executed political prisoners to make it absolutely clear that thosewho express any form of dissent – whether by speaking out or writing or attendingdemonstrations – will face the harshest penalties.“I hope your daughters grow up to get married – mine grew up to be thrown into jail”. So saidthe mother of Shiva Nazar Ahari, one of the detainees whose case is highlighted in this report,to Amnesty International – poignantly illustrating the journey taken by an increasing number ofIranians, from political and civil activism and street demonstrations to the cells of Evin Prisonand beyond. This report describes that journey in detail, showing how ordinary an experiencearrest and detention has become. Iranians in large numbers are being imprisoned for peacefullyexercizing their rights. Not only should they not be incarcerated in the first place, but whileheld they are further abused and victimized. The report clearly demonstrates that the vastmajority of international standards related to the protection of detainees, as set out in the UNBody of Principles for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention orImprisonment, are ignored. Judicial guarantees in Iranian law are also routinely flouted.Over the past year, Iran has faced mounting international criticism of its human rights recordboth by individual states and within international fora such as the United Nations GeneralAssembly and the Human Rights Council, where Iran’s record was considered in the frameworkof the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) in February 2010. While accepting genericrecommendations at the conclusion of the process, other specific recommendations wererejected, which had they been adopted and implemented could have significantly improved thesituation for detainees and prisoners in Iran. Consolidated international pressure on Iran in therun up to the election in May for membership of the Human Rights Council appears to have ledto the withdrawal of Iran’s candidacy at the last minute.At times, the reality of the situation for prisoners in Iran has been on the lips of the world, suchas the campaign for the release of renowned film director Ja’far Panahi which culminated inhis empty chair on the jury for the Cannes Film Festival. However, his welcome release shouldnot obscure the fact that hundreds of others remain held – for similar reasons – who have noone to speak so eloquently for them.This report is an attempt to address that fact and to ensure that the worst nightmare ofreleased detainee Maziar Bahari does not become a reality for those still held. It focuses on thesituation of detainees and prisoners in Iran – most of whom are prisoners of conscience6whoshould be released forthwith – while recognizing that many other egregious human rightsviolations in Iran deserve attention in their own right. It looks at the people targeted for arrest,who are drawn from a widening circle of the population, how arrests are made, where detaineesare held, the conditions of detention, and the pressures placed on detainees to make“confessions” that are then used as the main evidence against them in trials which arefundamentally flawed and are often summary, particularly in the provinces away from the glareof publicity in Tehran.The report analyses the vaguely worded legislation used to charge those arrested with“offences” that do not meet the requirements for clarity and precision in criminal law outlinedin international law. It looks at the political pressures exerted on judges to convict people, andthe politically motivated use of the death penalty to send a warning to anyone considering opendefiance of the authorities.

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

7

The report ends with two essential calls on the Iranian authorities to immediately andunconditionally release all prisoners of conscience and to ensure that all other politicalprisoners are tried promptly and fairly, without recourse to the death penalty, in proceedingswhich fully meet international fair trial standards.Despite Iran’s assertion in its report submitted to the United Nations in the framework of theUPR in February 2010 that it co-operates with NGOs, Amnesty International has not beenpermitted to visit Iran for fact-finding purposes or to hold Government talks since 1979. Theorganization again sought access to Iran in November 2009, and was unable to even meet theAmbassador of Iran in London. Amnesty International delegates also sought a meeting with theIranian delegation presenting Iran’s human rights record at the UN for the Universal PeriodicReview of Iran in February 2010, but were rebuffed.This report is therefore based on interviews with family members of those held; their lawyersand friends; those who have been released, including some interviewed face-to-face in Turkeyin March 2010; statements by the Iranian authorities; media reports, both official and from theopposition; and reports by local and international NGOs concerned with human rights. AmnestyInternational’s lack of access to Iran has affected the ability of the organization to verifydirectly all violations brought to its attention. However, it believes the wide range ofinformation below illustrates the plight of the hundreds of people detained without charge ortrial, or sentenced to lengthy prison terms, flogging or death after unfair trials simply forexpressing their dissenting views.The report follows an earlier report issued by Amnesty International in December 2009,Iran:Election contested, repression compounded,which documented human rights violations before,during and after the election up to mid-November 2009.7Amnesty International hopes thatthis report too will help break the wall of silence which the Iranian authorities are trying toerect, and will contribute to an eventual improvement in the human rights situation for all inIran. Alongside the publication of this report, the organization is launching a year-longcampaign, which will focus on the situation of a number of prisoners of conscience andpolitical prisoners to highlight the plight of the hundreds still held.Amnesty International wishes to thank all those who contributed to this report, and to paytribute to those who have allowed their stories to be told, in the hope that others may not sufferin the same way. In particular, the families and friends of detainees and prisoners who – at nosmall risk to themselves – have continued to speak out to ensure their loved ones are notforgotten, deserve our admiration. It has only been possible to mention a small proportion ofthose who are still suffering, but this is not to downplay the suffering of others – and weencourage all who have such information to come forward and speak out, so that no one isforgotten and so that the international community cannot turn a blind eye to the human rightsviolations which continue unabated in Iran.

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

8

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

2. WHO ARE THE PRISONERS?“Silence has usually harmed, rather than helped,political prisoners.”Roxana Saberi, former prisoner of conscience,The Washington Post,13 May 2010

All those arrested, detained and imprisoned in the fallout after the election have one thing incommon: they are perceived as challenging the authorites’ legitimacy and in some way offeringan alternative view of events to that presented by the authorities.The vast majority of the well-over 5,000 arrested since June 2009 have been ordinary citizens– women and men, workers and the unemployed, students and professionals – who went outinto the streets to protest against the announced election result, or against human rightsviolations that occurred. Most were released after days or weeks, but some were held formonths. Some still languish in the harsh conditions prevalent in most of Iran’s prisons,particularly in the provinces. These are the “nameless” prisoners (gomnam) – the lesser-knownpeople whose cases have not garnered much media attention.8In addition to these prisoners, there have been sweeping arrests before and afterdemonstrations which since July have taken place only on days of national importance whenpublic demonstrations are generally held, such as Qods Day, the last Friday of Ramadan, theanniversary of the seizure of the US Embassy on 4 November 1979, National Students’ Day on7 December, and the religious festival of Ashoura (the 10th day of the Islamic month ofMoharram which fell on 27 December in 2009).Those targeted for arrest have included political and human rights activists, journalists,women’s rights defenders and students. As time has progressed, new groups have been broughtinto the fold of suspicion, including clerics, academics, former political prisoners and theirrelatives, people with family links to banned groups, members of Iran’s ethnic and religiousminorities−particularly the Baha’is, but also other minorities such as Christians, Dervishes,Azerbaijanis, Sunni Muslims(whoare mostly Baluch and Kurds), and lawyers who havedefended political detainees.Amnesty International has been unable to compile and maintain complete lists of all thosecurrently detained or imprisoned. This is due to the secrecy surrounding arrests, includingpressures placed on families not to report arrests; the difficulty of obtaining information fromIran, where the security services monitor phone calls, email and other internet-based forms ofcommunication; and the “revolving doors” of prisons and detention centres, whereby peopleare detained for relatively short periods, sometimes repeatedly, or prisoners are releasedpending appeal or “temporarily” for weeks or months. However, a small number of individualswhose cases have been brought to the organization’s attention are highlighted below toillustrate the pattern of violations against those held.

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

9

POLITICAL ACTIVISTS"These two parties [the Islamic Iran Participation Front and the Mojahedin of the Islamic RevolutionOrganization] played an important role in [post-] poll seditions, thus the system, to prove its power,should act firmly with the transgressors."Ruhollah Hosseinian, Head of the Domestic Policy and Councils’ Affairs Committee of the Majles, in April 2010 following the banningof two parties9

While the two main opposition leaders – unsuccessful presidential candidates Mir HosseinMousavi and Mehdi Karroubi – remained at liberty at the time of writing, they have facedthreats of arrest, and their movements and whom they meet are closely monitored.10MehdiKarroubi’s car has been attacked, one of his sons was banned from leaving the country, andanother was arrested and beaten during a rally held on the anniversary of the establishment ofthe Islamic Republic on 11 February. Mir Hossein Mousavi’s nephew was killed in the Ashourademonstrations, and his personal bodyguard was arrested in mid-May 2009.However, many senior members of political parties such as the Islamic Iran Participation Front(IIPF), a political party linked to former President Mohammad Khatami, and the Mojahedin ofthe Islamic Revolution Organization (MIRO), which endorsed Mir Hossein Mousavi’s candidacyin the 2009 presidential election, were arrested in the days after the election. The two partieshave since been banned.11Arrests have continued – for example, former parliamentarianMohsen Armin,a spokesperson and senior member of MIRO, was arrested from his home on 16May 2010.Other parties whose members have been targeted for arrest include the Servants ofConstruction (SOC), which is close to former President and Chair of the Expediency CouncilAyatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani; the National Trust party, headed by Mehdi Karroubiwhich was closed down in August 2009; and the banned but tolerated Freedom Movement, ledby Ebrahim Yazdi. Many were later sentenced to prison terms, but some had been freed on bailpending appeal or for “temporary prison leave” at the time of writing. They includeAzarMansouri,a senior member of the IIPF, as well asAbdollah Ramazanzadeh,the party’s DeputyChairman, sentenced to three years and six years in prison respectively and both released onbail. Others currently at liberty areMohammad Atrianfar,a journalist and member of the SOCwho was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in November 2009, but released on bailpending an appeal.The liberty of those released conditionally is precarious.Mohsen Mirdamadi,for example, theChairperson of the IIPF, was returned to prison on 26 May 2010 after his release on bail twomonths earlier in March. He was sentenced in April to six years in prison.Behzad Nabavi,aformer Deputy Minister, parliamentarian and founding member of MIRO, returned to prison inlate May 2010 to continue serving a five-year prison term after having been releasedtemporarily on 16 March 2010.Hengameh Shahidi,a journalist and member of the NationalTrust party who acted as an adviser on women’s issues to defeated presidential candidateMehdi Karroubi during his election campaign, began serving a six-year prison sentence on 25February 2010 after an appeal court upheld the conviction on charges related to her politicaland journalistic activities. Hengameh Shahidi, who is in poor health, had been arrested on 30June 2009 and released on bail in November.Others have never been released and remain imprisoned. Among them isFarid Taheri,amember of the Freedom Movement, arrested in January 2010 and sentenced to three years inprison in April 2010 for “gathering and colluding with intent to harm state security”,“propaganda against the system and “disturbing public order”.

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

10

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

Members of smaller political parties have also been targeted.Heshmatollah Tabarzadi,aged53, leader of the banned Democratic Front of Iran, was arrested on 27 December 2009 at hishome in Tehran after the Ashoura protests. He has been held since then without charge or trialor access to a lawyer. His arrest may be linked to some of his articles and interviews whichappeared before and during the Ashoura unrest.Some activists have been arrested several times.Emad Bahavar,Head of the Youth Wing of theFreedom Movement, which was active during the presidential campaign, has been arrested fourtimes since the start of 2009 apparently in connection with the election, including thecampaign beforehand.Most recently he was arrested in March 2010 when he was summonedto court only days after being released. He was mentioned in the second mass “show trial” ofAugust 2009, during which the Freedom Movement was accused of being part of the “softrevolution” which the authorities claimed was aimed at overthrowing the Islamic Republic.Held without charge or trial, he was said to be under pressure to make a televized “confession”at the time of writing.Many other members of political parties, especially from provincial branches, have beenarrested in the months following the election – such asDr. Hossein Raisian,a universityProfessor and member of the Qazvin branch of the IIPF, who was arrested in May 2010.Officials later said that he had been arrested on suspicion of an illicit relationship, but DrRaisian later reportedly told his wife that these accusations were untrue and were politicallymotivated. For the majority, even when reports of their arrests have surfaced, their fates remainlargely unknown, highlighting the extra layer of secrecy surrounding those detained in theprovinces.

STUDENTS AND GRADUATESMembers of the student body, the Office of the Consolidation of Unity ( Daftar-e Tahkim-eVahdat, OCU), and the Graduates’ Association (Advar-e Tahkim-e Vahdat) have been targetedfor arrest. Both organizations have been prominent in promoting human rights, reporting onhuman rights violations and calling for political reform in recent years.Members of the OCU Central Committee currently held includeBahareh Hedayat,also Chair ofthe OCU’s Women’s Committee, andMilad Asadi.In May 2010 they were sentenced to nineand a half years and seven years in prison respectively. Bahareh Hedayat’s husband, AminAhmadian described how their trials were held behind closed doors without their lawyers beingpresent and added:"This ruling has no legal basis and has been issued on a political basis. On the threshold of theanniversary of the elections and the attack on the Tehran University dormitories, I think theywanted to issue heavy sentences for two distinguished student activists”.12Morteza Samyari,aged 24, another member of the Central Committee, was released on bail inFebruary 2010, pending an appeal. Arrested on 4 January 2010, he was sentenced to six yearsin prison after he was convicted of “propaganda against the system” and “gathering andcolluding with the intent to act against national security”, following a “show trial” that beganon 30 January 2010 (see Chapter 5).Mehdi Arabshahi,Secretary of the OCU, arrested afterthe Ashoura demonstrations on 27 December, was released on bail on 11 March 2010 and hasyet to be tried.Student leaderMajid Tavakkoliwas beaten and arrested on 7 December 2009 after making aspeech at a student demonstration in Tehran. His lawyer was not permitted to attend his trial,which took place in January 2010, after which he was sentenced to eight-and a half years inprison. He was also issued a five-year ban on any involvement in political activities and on

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

11

leaving the country. In May 2010 he went on hunger strike to protest at his transfer to solitaryconfinement until he was moved back to a general ward.The day after his arrest, the Fars News Agency, which is close to the Revolutionary Guards andthe Judiciary, published pictures of Majid Tavakkoli wearing women’s clothing, and said he hadbeen wearing them at the time of his arrest in order to escape detection. Student sources havedenied that he was wearing the clothes at the time, but suggested he was forced to wear themafterwards to humiliate him.After Majid Tavakkoli was pictured wearing women’s clothes, many Iranian men took picturesof themselves with head coverings, many of them holding signs saying “We are Majid”, andposted them on the internet as part of a solidarity campaign calling for his release.13The Graduates’ Association, comprised mainly of former students who had been active in theOCU while studying and which in recent years has promoted reform and greater respect forhuman rights, said in May 2010 that over half of its members had been arrested since theelection.They includeAhmad Zeidabadi,a journalist and Secretary-General of the Graduates’Association, who was arrested on 21 June 2009 and held incommunicado in Evin Prison untilhis appearance on 8 August 2009 at the second session of a mass “show trial”. He wassentenced to six years’ imprisonment in November 2009, five years of internal exile in the cityof Gonabad, and a lifetime ban on all social and political activities. At the end of January2010, he was transferred to Raja’i Shahr Prison in Karaj, near Tehran, where most non-political prisoners are housed. Even though his family posted bail, he has not been freed.Another senior member of the Association,Abdollah Momeni,who also appeared in a “showtrial” in August, was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in November 2009, and a previouslysuspended sentence of two years’ imprisonment was also implemented. In May 2010, this wasreduced to four years and eleven months on appeal. Also in May,Kohzad Esma’ili,the Head ofthe organization’s Gilan branch, had his three-year sentence upheld on appeal. Others havebeen released on bail, includingSalman Sima,but some have been banned from leaving thecountry, such asHasan Asadi ZeidabadiandMohammad Sadeghi.Both had been arrested inNovember 2009.Hundreds of students who have participated in demonstrations in the streets or on universitycampuses have been arrested and some have been sentenced to prison terms. For example,Amnesty International obtained court documents relating to the trial of eight students, allmembers of the Islamic Society in the Babol Noshirvani University of Technology, northernIran. They were found guilty in September 2009 of acting against the Islamic Republic by“participating in an illegal gathering”, “encouraging people to riot” and “propaganda againstthe state”. In February 2010, a court of appeal upheld the sentences ofIman Sedighi, MohsenBarzegarandNima Nahavito 10 months in prison.Mohsen Esma’ilzadehhad his 91-dayprison sentence for “insulting the Supreme Leader” upheld. Five others were sentenced to 10months’ suspended imprisonment and a one-year ban on studying. At the time of writing, ImanSedighi, Mohsen Barzegar, Nima Nahavi and Mohsen Esma’ilzadeh were all serving theirsentences in Mati Kalay Prison in Babol.

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

12

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

JOURNALISTS“This year, we bloggers and journalists are celebrating World Press Freedom Day in prison. We havebeen jailed and given unjust sentences for wanting to inform, for writing articles, for carrying outinterviews and for participating in the debate about freedom and democracy. Purely and simply fordoing our duty as journalists.”Open letter from 20 detained journalists for World Press Freedom Day 201014

Journalists have been particularly targeted, perhaps because it is in the very nature of theirwork to uncover the truth and comment on events. Well over 100 journalists, many of whomworked for publications perceived by the authorities as “reformist”, are believed to have beenarrested, and over 5015of them remain detained or imprisoned or on temporary leave at risk ofreturn to prison at the time of writing. There are frequent reports of further arrests, in additionto the banning of publications – over 20 since the election – which has left an estimated3,000 people without work.16Some of those sentenced are free on bail pending appeal or on “temporary” release, such asSaeed Laylaz,sentenced to six years. Like others, some journalists released temporarily haveexperienced the fragility of their freedom:Bahman Ahmadi Amou’i,whose seven year and fourmonth sentence was reduced to five years on appeal, returned to prison in late May 2010 after72 days, Others have never been released and are serving heavy prison sentences, such asMasoud Bastani,a journalist forJomhouriyat,who was arrested in July 2009. He is serving asix-year prison sentence in harsh conditions at Raja’i Shahr Prison, in Karaj, near Tehran.Mehdi Mahmoudian,a journalist who first revealed abuses at the Kahrizak Detention Centre17and was arrested on 16 September, was sentenced to five years in prison in May.Still others have yet to be charged or tried, despite having spent months in detention. Manyhave been held in solitary confinement in prisons where they risk torture or other ill-treatment,including beatings, threats and mock execution. They include veteran journalistIsa Saharkhizwho was active in Mehdi Karroubi’s election campaign, and who has been detained withoutcharge or trial for over 11 months. He was transferred to Raja’i Shahr Prison in May, which hisfamily consider to be a form of punishment.Prominent human rights defender and journalistEmadeddin Baghi– the 2009 recipient of theprestigious Martin Ennals Award for human rights defenders – was arrested on 28 December.In November he had been banned from travelling to Geneva to accept the award, the first timein the award's 18-year history that the recipient was denied the opportunity to receive theaward in person. His arrest followed the broadcasting several days previously of an interview hehad recorded two years earlier with Grand Ayatollah Montazeri, which was shown on BBCPersian TV to mark the cleric’s death.18He was arrested at a time of mass protests in Tehranand other cities to mark Ashoura. He remains held without charge.Badrolsadat Mofidi,Secretary of the now-banned Association of Iranian Journalists, wasarrested after the Ashoura demonstrations following an interview she had given a week earlierto the German international broadcaster Deutsche Welle in which she described the crackdownon the press. She remains held without charge or trial at the time of writing.All three are suffering ill-health in detention and there are fears that the medical care they arereceiving is inadequate.

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

13

FILMMAKERS AND OTHER ARTISTS“Specific Iranian productions might not receive permission for a foreign premiere… One [filmmaker]was recently warned against any attempt to screen his movie at foreign festivals.”Alireza Sajjadpur,Director of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance’s Supervision and Evaluation Office, April 201019

Those involved in culture have not been immune from arrest or harassment, particularly whenthe authorities fear that the art will be used to present a dissenting voice to the world.Screenplays must be vetted by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance to receive aproduction licence and then a screening licence for both domestic and foreign showings. InMay 2010, a Ministry of Culture official said that Iranians must also obtain permission beforeco-operating in foreign productions.20Celebrated movie directorJa’far Panahiwas released on 25 May 2010 after almost threemonths in detention without charge or trial, after his plight was highlighted at the Cannes FilmFestival.Mohammad Nourizad,a director as well as a journalist, was on hunger strike at thetime of writing after he was beaten in prison. He was arrested in December 2009 andsentenced to three and a half years’ imprisonment and 50 lashes for “insulting the authorities”and “propaganda against the state” for articles published on his blog criticizing the SupremeLeader and the Head of the Judiciary.His sentence was upheld on appeal in late May, shortlyafter he described being pulled from his cell without warning and beaten – possibly in reprisalfor a letter to the Supreme Leader which he wrote in April 2010, criticizing his treatment andimprisonment.21Mohammad Ali Shirzadi,a documentary filmmaker, was held without charge or trial at the timeof writing. His arrest in December is believed to be linked to an interview he filmed betweenprominent human rights defender Emadeddin Baghi and Grand Ayatollah Montazeri. Since hisarrest, Mohammad Ali Shirzadi has had around three family visits and no access to his lawyer.Other artists detained includeMehraneh Atashi,an internationally-renowned photographer whowas arrested with her husbandMajid Ghaffariin January. They were released on bail in March2010. Some have been harassed, including 82-year-old poetSimin Behbahaniwho wasbanned from travelling to France in March where she was due to speak at an InternationalWomen’s Day event.

RIGHTS DEFENDERS“As far as we understand from our daughter’s writings and activities, she has not done anything exceptsome human rights activities. In her attempts to realize this goal, she does her best to defend everyreligion and ideology. Is it a crime to defend human rights?”Shiva Nazar Ahari’s parents in a letter to the Ministry of Intelligence after her arrest in December 2009

The Iranian authorities have been keen to discredit human rights activists, including citizenjournalists who have been at the forefront of gathering information about human rightsviolations, including testimonies from families and occasionally from released prisoners. In anapparent attempt to provide scapegoats for their distorted version of events, the authoritieshave accused some human rights NGOs of being in contact with, or supplying information to,banned groups, particularly the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI) and havecarried out waves of arrests of human rights activists.For example, at least eight members of the Committee of Human Rights Reporters (CHRR)have been arbitrarily arrested since the end of November 2009. Two of them –Shiva NazarAhariandKouhyar Goudarzi– were still detained in May 2010. Their trials had begun, but hadnot been concluded. Others arrested and later released includeSaeed Kalanaki, Saeed

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

14

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

Jalalifar, Saeed Haeri, Parisa Kakayi, Mehrdad RahimiandNavid Khanjani.Some membershave fled the country for their own safety. In January 2010 the Tehran Prosecutor accused thegroup of having links to the PMOI, and said that “any collaboration with the [CHRR] is acrime”. The CHRR vehemently denies having such links.Another human rights organization, Human Rights Activists in Iran (HRAI), has also beentargeted. In early March 2010, a wave of arrests of individuals who are or have been associatedwith the organization was carried out. Many of those arrested remained held at the time ofwriting. On 17 March 2010, the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office said that 30 people had beenarrested in connection with alleged US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) “cyber networks” thatwere aimed at destabilizing Iran, and said that HRAI was part of this. On 26 March 2010, theHRAI published a list of 41 of its members and associates who it said had been arrested. Itsaid “the only crime of these activists is their philanthropy and their work toward helpinghumanity”.22They includeMahboubeh Karami(who is also a member of the One MillionSignatures Campaign−see below) andAbdolreza Ahmadifrom Tehran;Mohammad Reza LotfiYazdifrom Mashhad;Mojtaba Bayatfrom Qom;Tahmineh Momenifrom Sari;Sepehr Soufifrom Kish Island;Somayeh Ojaghloufrom Esfahan; andMojtaba Gahestounifrom Ahvaz; andSaleh Shalmashifrom Sanandaj. Some of them have since been released.Abolfazl Abedini Nasr,a 28-year-old journalist and human rights activist from Ramhormuz,Khuzestan province, who was formerly a Press Officer for the HRAI, has been particularlyharshly treated. He was first arrested in late June 2009 and was held for four months inSepidar Prison, in Ahvaz, near Iran's border with Iraq, until he was released on bail on 26October 2009. On 3 March 2010, during a wave of arrests of human rights activists, he wasrearrested at his home in Ramhormuz. During his arrest he was beaten by security officials.Four days after this arrest, he was taken to Evin Prison, where he is also reported to have beenbeaten.After his rearrest, Abolfazl Abedini Nasr’s lawyer was informed on 29 March 2010 that hisclient had been sentenced to 11 years in prison in connection with his earlier arrest in June2009. This consisted of five years’ imprisonment for “membership of an illegal organization”,in relation to his involvement with the HRAI, one year’s imprisonment for “propaganda againstthe system” for talking to foreign media and five years for “contacts with enemy states”. The“contact with enemy states” may be related to claims that the authorities made in March 2010that the HRAI was set up by the CIA as part of alleged attempts to orchestrate a “softrevolution” in Iran. His sentence was confirmed on appeal in May 2010. He suffers from aheart defect which requires regular medication and check-ups.Sayed Ziaoddin Nabaviisa member of the Council to Defend the Right to Education, a body setup in 2009 by students barred from further study because of their political activities or on accountof their being Baha’is. He was arrested in June 2009, along with his cousin Atefeh Nabavi whowas later sentenced to four years in prison. Sayed Ziaoddin Nabavi was sentenced to 15 years’imprisonment and 74 lashes in January 2010, which was reduced to 10 years on appeal in lateMay. He says that he was beaten, kicked, insulted and humiliated during his interrogation. Hisparticularly heavy sentence appears in part to be linked to the fact that he has family membersbased in PMOI-run camps in Iraq. He denies having any personal links to the PMOI.Members of other human rights organizations have also been arrested, and some tried andsentenced.Ali Bikas,a member of the Student Committee for the Defence of PoliticalPrisoners (SCDPP) and an activist for the rights of the Iranian Azerbaijani minority, is serving aseven-year prison term in Evin Prison. Another member of the SCDPP,Naseh Faridi,wassentenced to six years in prison and 74 lashes in January. He is currently free on bail pendingan appeal. Another board member of the SCDPP, lawyerMohammad Olyaeifardis also

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

15

imprisoned (see section on lawyers below).Kaveh Ghasemi Kermanshahi,spokesperson for theHuman Rights Organization of Kurdistan23and a member of the One Million SignaturesCampaign which campaigns for greater respect for women’s rights, was arrested in February2010 in Kermanshah, western Iran. He was released on bail on 23 May 2010.Children’s rights activists have not been spared either: for example,Maryam Zia,Director of theAssociation for the Endeavour for a World Deserving of Children, was arrested on 31 December2009. She was eventually released on bail in March 2010 after she had gone on hunger strikein protest at her continued detention. Women campaigning for redress for human rightsviolations have also been targeted: members of the Mourning Mothers, a group of motherswhose children were killed in the post-election demonstrations and their supporters, have beenarrested on several occasions. Members of the group meet silently in parks on Saturdays toregister their protests. Over 30 were arrested in January, although most were released withindays.24Women’s rights defenders too have faced the authorities’ ire. Although immediately after theelection there was a lull in arrests of women’s rights activists, the women’s movement wasnamed in the general indictment read at the first “show trial” as being part of the “velvetrevolution” and arrests resumed in October.Shadi Sadr,a prominent lawyer and women’srights defender who was detained for a week in July 2009, was sentenced in her absence to sixyears in prison and 74 lashes along withMahboubeh Abbasgholizadeh,another women’s rightsdefender, who was sentenced to two-and-a-half years’ imprisonment and 30 lashes.25Bothwere convicted in relation to a peaceful gathering in 2007 – a move widely interpreted asintended to discourage people from protesting on the anniversary of the election.Among those particularly targeted have been supporters of the One Million SignaturesCampaign (also known as the Campaign for Equality), a women’s rights initiative launched in2006. Its volunteers are collecting a million signatures of Iranians demanding an end to legaldiscrimination against women in Iran, such as exclusion from key areas of the state, includingstanding for the presidency, and in the areas of marriage, divorce, child custody andinheritance. Even though the Campaign for Equality conducts its activities in full compliancewith the law, the authorities have impeded its work and repressed its activists. They haveblocked access to the campaign’s main website at least 23 times, frequently denied the grouppermission to hold public meetings, prevented activists from travelling abroad or summonedthem for interrogation, and apparently been behind threatening phone calls.More than a dozen members of the Campaign for Equality have been arrested since October2009. They includeRahaleh AsgarizadehandVahideh Molavi,arrested during protests inTehran on 4 November 2009, and two men,Mohsen Parizad MoghaddamandAli Mashmooli,arrested in Esfahan, central Iran, on the same day. All were later released.Mehrnoush Etemadiwas arrested at home in Esfahan on 23 November 2009 and was releasedon bail in December. Accusations made against her included “membership of the One MillionSignatures Campaign”.Hayedeh Tabeshwas arrested on 5 December 2009, also in Esfahan.Both were released on bail on 8 December. Hayedeh Tabesh had previously been banned fromtravel abroad because she had been invited to a training event in South Africa, even though shedid not participate in the event.Other Campaign members arrested after Ashoura includeAtiyeh Yousefi,held for about twoweeks in the northern city of Rasht;Somayeh Rashidi,arrested in December and held for 68days; andMansoureh Shojaee,held for almost a month in Tehran. Mansoureh Shojaee hasbeen banned from travel for the past three years.

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

16

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

Others were arrested in the run-up to the anniversary of the Islamic Revolution in February2010. They includeMaziar Samiee,a student and Campaign for Equality activist. He was heldfor two weeks in February 2010.Mahsa Jazini,a journalist forIran Dailyand an activist in theCampaign for Equality, was arrested on 7 February 2010 in Esfahan and released on bail on 1March. She was told at the time of her arrest that the reason for her detention was that she wasa feminist.Noushin Ja’fari,another journalist, was also held for about a month after her arrestin early February 2010.Dorsa Sobhani,a Campaign for Equality member in Sari, near the northern Caspian Sea coast,was arrested on 7 March 2010 and held until 21 April. A member of the Baha’i minority, shehad been banned from continuing her university studies on account of her faith, and afterwardsjoined the Council to Defend the Right to Education.Somayeh Farid,a Campaign activist whois also a member of the Graduates’ Association, was arrested in Tehran on 16 March 2010when she went to inquire about her husband who had been arrested. She was released on bailafter almost two weeks.

LAWYERS“Given that my sister has always defended legal rights of students and political activists, it is mostupsetting that she is now deprived of her own legal rights.”Hossein Mirzaei, the brother of Forough Mirzaei, during her detention in January 201026

The Iranian authorities appear to be taking measures to limit the access of Iranians to high-quality, independent legal representation. In addition to measures to limit the independence ofthe Iranian Bar Association, such as barring candidates from standing for election to seniorpositions on discriminatory grounds, including their imputed political opinions, several lawyershave also been arrested, apparently on account of their work or their political beliefs.Mohammad Olyaeifard,who has defended cases of juvenile offenders as well as imprisonedjournalists and trade unionists (he is the lawyer of Abolfazl Abedini Nasr mentioned above),was arrested on 1 May 2010 to begin serving a one-year jail term imposed for “propagandaagainst the system”. His lawyers have not been informed of his sentence, in violation of Iranianlaw. Before his arrest, Mohammad Olyaeifard said that he had been convicted on 7 February2010 because of an interview critical of the Judiciary he gave to Voice of America’s PersianService shortly after his client, juvenile offender Behnoud Shojaee, was hanged in October2009 for a murder he committed when he was 17 years old. Executions of those under the ageof 18 at the time of their alleged offence are strictly prohibited under international law.Other lawyers arrested includeVahid Talaei,a member of Mir Hossein Mousavi’s legal team. Hewas arrested on 4 or 5 May 2010 and held for over two weeks.Forough Mirzaeiwas arrested on2 January 2010 along with her husband, journalist Roozbeh Karimi. She was released on bailon 9 February, but Roozbeh Karimi remained held until the end of February.Some arrested earlier and released on bail continue to face the possibility of charge and trial,which could result in loss of their licence to practise. They includeMohammad Ali Dadkhah,awell-known human rights lawyer and member of the Centre for Human Rights Defenders, whowas arrested in July 2009 and held for one month. The prosecutor in one of the “show trials”in August 2009 alleged that “[guns], bullets, drugs, documents revealing ties with foreigncountries for the purpose of creating chaos and documents ... revealing orders for riots andprotests” were found in Mohammad Ali Dadkhah’s office. After a trial session in December2009, his case was referred for a retrial on the grounds of flaws in the investigation.27TheIranian authorities have a history of bringing what appear to be politically-motivated criminalcharges against human rights lawyers – for example, Nasser Zarafshan served five years’ inprison after he was convicted in March 2002 on similar charges.28

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

17

CLERICSMembers of Iran’s clerical establishment have also been targeted. Some reformist clerics,particularly those close to the late Grand Ayatollah Montazeri, have been detained.Ayatollah Mohammad Taghi Khalaji,a supporter of Grand Ayatollah Montazeri, was arrested on12 January 2010 at his home in Qom. Since the disputed presidential election in June 2009,he had made several speeches critical of the authorities, including their use of violence againstpeaceful protesters for which he received warnings from the authorities. He had also called fora peaceful resolution of the tension between the Government and Opposition. He was releasedon bail on 1 February 2010.Seyyed Ahmadreza Ahmadpour,a reformist cleric in Qom and member of the CentralCommittee of the IIPF, was sentenced to one year’s imprisonment and defrocked by theSpecial Court for the Clergy in March 2010. He had been arrested during the Ashoura protestsand released on 10 January.Qom Mofid University Law School teacherHojjatoleslam Mostafa Mir Ahmadizadeh,also closeto Grand Ayatollah Montazeri was held between 26 February and 17 March 2010 and was notknown to have been tried at the time of writing.Ahmad Qabel,a reformist cleric, was arrested from a bus on 20 December 2009 while on hisway to participate in Grand Ayatollah Montazeri’s funeral. In mid-March 2010, he contactedhis family and told them that he had been transferred to the quarantine section of VakilabadPrison in Mashhad after 70 days of detention. He also said that he had appeared before aRevolutionary Court, to which he had been taken in chains, as the authorities in Mashhadrefused to recognize his religious credentials. He said that his passport and house had beenconfiscated.29

PEOPLE LINKED TO MEMBERS OF BANNED GROUPS“Elements such as the hypocrites [PMOI], the monarchists, religious and ethnic terrorists, Baha'is,homosexuals, feminist groups, nationalists and Marxists are participating in this [seditious] current.”Minister of Intelligence Hojjatoleslam Heidar Moslehi, December 200930

The Iranian authorities have sought to blame banned groups for the unrest, particularly thePMOI which is based in Iraq. Other groups blamed include left-wing groups, sometimesidentified as “neo-communist”, and monarchist groups, particularly the Kingdom Assembly ofIran and the associated Tondar group.31To find scapegoats and to validate their claims of a“soft revolution” orchestrated from abroad, they have turned to former political prisoners and tothose whose relatives are members of banned groups, particularly the PMOI, whom they callthe “hypocrites” (monafeqin). They have arrested targeted people and charged them with linksto such groups.Arrests of people the authorities claim are linked to the PMOI took place in September andDecember 2009, around demonstrations on Qods Day and Ashoura. On 27 January, a DeputyIntelligence Minister said that among the more than 1,000 people arrested on Ashoura were20 members of the PMOI, who would face charges ofmoharebeh(enmity against God). Thosearrested in September includeJa’far KazemiandMohammad Ali Haj Aghaei,both latersentenced to death, andZahra Jabbari,sentenced to four years’ imprisonment in May 2010.Monireh Rabi’iwas arrested in October 2009 and has been sentenced to five years in exile.Most, if not all, have relatives in the PMOI-run Camp Ashraf in Iraq.Ahmad Daneshpour Moghaddam, Mohsen Daneshpour Moghaddam, Mottahareh BahramiHaghighi, Rayhaneh Hajebrahim DabbaghandHadi Ghaemiwere all arrested after Ashoura and

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

18

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

sentenced to death after a “show trial” in January 2010 where they were convicted ofmoharebeh.Ahmad Daneshpour Moghaddam and his father Mohsen had their death sentencesconfirmed on appeal, although the sentences of the other three were commuted.Two other men alleged to have links to the PMOI and to have been involved in organizing theAshoura unrest are also facing execution – teacherAbdolreza Ghanbari,who was among 16people who appeared in a “show trial” in January and February; andAli Saremi,who has beenin detention since 2007.Former political prisoners and their relatives have also been arrested.Zohreh Tonekaboni,aged62 and a member of Mothers for Peace,32was arrested on 28 December 2009 and held forover a month. A former prisoner of conscience for whom Amnesty International campaignedwhen she was imprisoned in the 1980s,33she is also the widow of a prisoner killed during the1988 “prison massacre”. Her friend, historianMahin Fahimi,a co-member of Mothers forPeace, was arrested the same day with four others. Mahin Fahimi’s sonOmid Montazeri(seebelow) was arrested the next day. Mahin Fahimi’s husband, Hamid Montazeri was a victim ofthe 1988 “prison massacre”.34Mahin Fahimi is also the aunt of Sohrab Arabi, unlawfully killedduring the June/July 2009 demonstrations whose death has never been investigated.35On 27 January 2010, a Deputy Minister of Intelligence alleged that about 30 people detainedin connection with the Ashoura demonstrations had links to left-wing groups, naming thePeople’s Fedaiyan Organization of Iran, both its Majority and Minority factions, or had neo-communist sympathies, in relation to which he named Mothers for Peace, which campaignsagainst possible military intervention in Iran over its nuclear programme, seeks “viablesolutions” to the region’s instability and campaigns against the arrest, detention andharassment of ordinary Iranians. The families of Zohreh Tonekaboni and Mahin Fahimi bothstrongly deny that they currently have any such links or that Mothers for Peace has any politicalaffiliations.Omid Montazeri,a 24-year-old law student and journalist who had written for the on-linecultural magazineSarpich,appeared in televized excerpts of the “show trial” of 16 people inJanuary and February 2010 and was accused of fomenting the Ashoura demonstrations as wellas having “neo-communist sympathies”. He was sentenced on 27 February 2010 to six years’imprisonment in a session which his lawyer was not allowed to attend. He was released“temporarily” for 10 days on 5 April 2010, and was not known to have returned to prison atthe time of writing.Other contributors toSarpichand their relatives have also been arrested.Ardavan Tarakmehwas arrested on 27 December 2009. StudentsYashar DarolshafaandMaziar Samieewerearrested during the night of 3/4 February. Yashar Darolshafa’smotherandbrotherwere alsoarrested, as was Ardavan Tarakmeh’s 25-year-old sisterBahar,but they were released two dayslater. Yashar Darolshafa’s two cousins,Banafsheh Darolshafayi,a music instructor, and hersisterJamileh,a script-writer and journalist, were both arrested on 5 February. Their father andmother,Abol Hassan DarolshafayiandSafoura Tofangchi,were arrested a few days later. Allwere later released by mid-March.

MEMBERS OF ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS MINORITIESAlthough members of Iran’s ethnic minorities did not participate to the same extent in thepost-election demonstrations, they have long been regarded with suspicion by the Iranianauthorities and remain so.Members of the Kurdish minority, such asKaveh Ghasemi Kermanshahi(see above), havecontinued to be arrested. In January 2010,Farzad Soltani,a Kurdish lawyer and supporter of

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

19

Mehdi Karroubi, was arrested. In May 2010, four Kurdish political prisoners were among fivepeople executed in an apparent warning to future demonstrators (see Chapter 5, Politicallymotivated use of the death penalty). The executions were widely condemned and a generalstrike was called in Kurdish areas. People arrested following the strike included at least fiveKurdish students in Marivan, close to the border with northern Iraq–Aram Veysi, Fu’adMoradi, Tofigh Partovi, Dana Lanjava'iandSaman Zandi.Spokesperson for the Human RightsOrganization of Kurdistan,Ajlal Qavami,was also arrested in Sanandaj, the capital ofKordestan province in west Iran, and held for several days.Members of the Azerbaijani minority have also been targeted, particularly around days ofsignificance to the Azerbaijani community. Football journalistAbdollah Sadoughiwas arrestedin Tabriz, north-west Iran, in January 2010 after publishing a poster supporting the localTraktor Sazi football team. He was released in March after going on hunger strike. In April2010, scores of Azerbaijanis gathered at Lake Oromieh, north-west Iran, to protest against theenvironmental damage being caused by continued extraction of the lake’s water. When securityforces arrived, they reportedly attacked demonstrators and fired tear gas and threw stones todisperse the crowds. They then arrested dozens of people.Behboud Gholizadehwas arrested in Miandoab, north-west Iran, on 21 May 2010. He is Headof the NGO Yashil whose licence had been withdrawn by the authorities after they alleged ithad a “separatist” agenda. Teacher and poetBahman Nasirzadehwas arrested the followingday in the town of Maku near the Turkish border. Their arrests may have been connected to theapproaching anniversary of the “cartoon demonstrations” held in May 2006 to protest against acartoon published in an Iranian newspaper that many Azerbaijanis found offensive. Both menhad been arrested during the 2006 demonstrations.

“They [some Baha’is] were arrested because they played a role in organizing the Ashoura protests andnamely for having sent abroad pictures of the unrest.”Tehran Prosecutor Abbas Ja’fari Dowlatabadi, 8 January 2010

As has happened at many points of tension during the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran,members of the Baha’i faith – an unrecognized religion in Iran – have been particularlytargeted.36Although some Baha’is marched alongside their compatriots in the earlydemonstrations, and were arrested alongside them, attacks against them have increased sincethe demonstrations on Ashoura. Following these protests, the scale of which seemed to catchthe authorities by surprise, officials sought to find scapegoats for what had happened. At least13 Baha’is were arrested in Tehran on 3 January 2010; most have been released, althoughone,Payam Fanaian,appeared in a “show trial” of 16 people in January and February. He wassentenced to six years in prison, which was reduced to one year on appeal.Artin Ghanzanfariwas held until 2 April, when he was released on bail, only to be summoned to court again on10 April, when he was told his release had been a “mistake”. He was not able to attend a courthearing on 13 April due to a lung infection.In total, around 50 Baha’is have been arrested in towns and cities across Iran since theelection. In mid-May 2010, at least 31 Baha’is were held, of whom some were arrested beforethe election. The authorities have announced that the next session of the trial of seven Baha’ileaders – who were responsible for administering the affairs of the Baha’i community in Iran –and who have been detained since March and May 2008, will be held on 12 June 2010 – thevery day of the anniversary of the election. Such a significant choice of timing cannot but beinterpreted as sending a message to the Iranian public to reinforce the authorities’ contentionof involvement of the Baha’i community in the post-election events.

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

20

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

“The circles for promotion of Christianity, Baha’ism, Wahhabism, Sufism... should be eliminated withthe efforts of the Law Enforcement Force as per God’s wish. The most significant psychological diseaseis created by these meetings and circles. They are corrupt and the biggest disrupters of the country’ssecurity.”Grand Ayatollah Vahid Khorasani37in a meeting with Qom province’s Law Enforcement Force commander, March 201038

Christians, Sufis and Sunni Muslims have also been targeted for arrest in recent months. Forexample,Yousef Naderkhanifrom Rasht, a member of the Only Jesus Church, was arrested on13 October 2009 and was believed to still be held at the time of writing. His arrest may havebeen linked to his protests about mandatory lessons about Islam in schools.A wave of arrests of Christians began in December 2009. According to Compass Direct News39Hamideh Najafiwas arrested in Mashhad on 16 December, and sentenced to three months’house arrest. The authorities also threatened to take her sick daughter into foster care. Fifteenothers were arrested during Christmas celebrations near Tehran. Days later three others werearrested in Esfahan, and at least seven were arrested in Shiraz, southern Iran.TheReverend Wilson Issavi,the Assyrian leader of the Evangelical Church of Kermanshah, wasarrested on 2 February 2010 in Esfahan and held for 54 days. His Church was sealed and hewas not allowed to reopen it after his release. In late February, two leaders of a house church inEsfahan – Hamid Shafi’i and his wife Reyhaneh Aghajari were arrested and were believed tostill be held at the time of writing.In May 2010, some 24 Gonabadi Dervishes from the Nematollahi order40were sentenced toprison terms and flogging for a demonstration outside a local Judiciary building in Gonabad,north-eastern Iran, in July 2009. The Dervishes had been protesting against the detention ofHossein Zara’i who had allowed a burial to take place in a cemetery used by Dervishes, despitean order banning such burials by the authorities. On 16 May 2010, theJavannewspaper,which is close to the Government, said that since the election of President Ahmadinejad in2005, “different Dervish groups have also strengthened their political activities against theIslamic Republic system in line with their foreign masters’ moves”.Sunni Muslims (who are mainly members of the Kurdish and Baluch minorities) in Iran havealso been arrested or harassed. In mid-May,Abdol Majid Esma’il Zahiwas summoned to theSpecial Court for the Clergy in Mashhad, north-eastern Iran for the third time in relation toarticles he had posted on his blog.Sheikh Hafiz Abdol Rashid,the Sunni Friday Prayer Leaderin Zabol, east Iran near the border with Afghanistan, was released on bail after six days indetention by the Special Court for the Clergy in Mashhad (see Chapter 5). He had beensummoned there on 11 May 2010 after he made a speech criticizing the destruction of aSunni seminary by the Iranian authorities two years ago.

WORKERS AND MEMBERS OF PROFESSIONAL BODIESWorkers and trade unionists are yet another portion of Iranian society which has been targetedfor arrest and harassment. At least 11 members of theIran Teachers Trade Associationwerearrested in November 2009 when celebrating World Teacher’s Day at a union meeting in thehome of the Association’s General Secretary. Most were released shortly afterwards.Independent Teachers’ Associations were banned by the Ministry of the Interior in 2007following huge demonstrations by teachers protesting at their conditions of employment, buthave never been formally dissolved by the courts. Other members of local Teachers’ TradeAssociations were harassed and briefly detained in the run up to International Labour Day on 1May and National Teachers’ day on 2 May 2010.

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

21

FAMILY MEMBERS OF PROMINENT FIGURES AND DETAINEESSome of those arrested appear to have had nothing to do with the demonstrations and unrestother than being relatives or friends of people arrested or wanted by the authorities. Theauthorities are reported to use the arrests of such people – who are usually held for days orweeks – as a means of putting further pressure on detainees or others. In at least some cases,it appears they are held in circumstances amounting to hostage-taking.Noushin Ebadi,a medical lecturer at the Azad University of Tehran and the sister of NobelPeace Laureate Shirin Ebadi, was arrested on 28 December and held for almost three weeks,apparently to put pressure on Shirin Ebadi, who is currently abroad, to stop speaking out abouthuman rights violations in Iran.Two sisters,LeilaandSara Tavassoli,were arrested on 28 December and 3 Januaryrespectively. Their father,Mohammad Tavassoli,who was also arrested after Ashoura, is activein the Freedom Movement, and their uncle,Ebrahim Yazdi,is the leader of the FreedomMovement. He too was arrested on 28 December but released for medical treatment inFebruary. Sara Tavassoli’s husband,Farid Taheri,was also arrested. Sara and Leila Tavassoliwere later released on bail and Sara Tavassoli was sentenced in late May 2010 to six years’imprisonment and 74 lashes for briefly participating in the Ashoura demonstrations and forvisiting Mir Hossein Mousavi and his wife after his nephew was killed during the Ashourademonstrations.The fiancée of Qazvin International University studentArsalan Abadiwho had been arrestedafter the Ashoura demonstrations, was reportedly arrested in February and held for 17 days inEvin Prison, in an apparent attempt to force him to “confess”. Two of his sisters were alsodetained. An initial charge ofmoharebehwas not accepted by the judge in his trial beforeBranch 15 of the Revolutionary Court in March. In May he was sentenced to nine and a halfyears in prison.

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

22

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

3. ARBITRARY ARREST ANDDETENTION“They ransacked our house …and took my childaway. For two months, no one gave me any answerswherever I went… [Then] my child called and said,Mother, I am all right. I asked, Where are you? Hesaid, I can't tell you… After that call, I didn't knowwhere to go. They don't give any response. I go tothe prison and they don't tell me anything.”Mother of Ahmad Karimi, sentenced to death after a “show trial”, in an interview with Voice of America, 5 January 2010.41

Those arrested during demonstrations by police or members of the Basij militia have usuallybeen taken to police stations for processing. Afterwards, they have often been taken to otherdetention centres for interrogation, including sections of Evin Prison, and most infamously, theKahrizak Detention Centre. Following the Ashoura unrest, there were also reports that detaineeswere held in the Vali Asr (Eshratabad) Garrison, a Revolutionary Guards’ base in Tehran, alsoknown as Prison 59 which had previously been closed.An unidentified individual gave the following testimony to HRAI in August 2009. WhileAmnesty International could not directly verify the details, it is consistent with other accountsof detention following mass arrests received by the organization.“I was arrested at about 10pm by anti-riot, plain clothes bike squads on one of the side streetsof Guisha (Kooye-Nasr). I was beaten and taken to [a] police precinct… along with more than20 people… the second we were arrested the plain clothes forces attacked us with batons andstarted beating us for no reason. They said we were rioters and that we had set police cars onfire. I had no clue what they were talking about… I was just crossing the street on my way to arelative’s house. I spent 25 days in prison for no reason and without having done anythingwrong.”42Those arrested from home or work were generally arrested by plain clothes security personnelwho did not identify themselves, and who generally showed only a generic arrest warrant, oftendated from some time before, and even from before the time of the election. Some werearrested in the street.

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

23

Iran’s Code of Criminal Procedure43empowers the police and the non-uniformed Basij andRevolutionary Guards to make arrests. Iran’s Supreme National Security Council may alsoempower other bodies or agencies to do so as well, although the basis and mechanism is notclear in the law and there appears to be no requirement for the authorities to inform the publicas to what bodies have been granted arresting and detaining powers. For example, Ministry ofIntelligence personnel do not appear in law to have the power of arrest, but under theseprovisions they may well have been given it.The lack of transparency of this system gives rise to abuse of the power of arrest, reinforcingthe practice of arbitrary arrest and detention that is already facilitated by flawed provisions inthe Penal Code and the Code of Criminal Procedure. The lack of transparency and oversightmechanisms allows the various forces to commit human rights violations with impunity.Well-known journalistMashaallah Shamsolvaezin,spokesperson for the Association of IranianJournalists and the Committee for the Defence of Press Freedom, was arrested on 28December 2010 at his home by plain clothes officials. Seeing that they had a printeddocument that had only the Revolutionary Court header but not any reference to his name orreasons for his arrest, Mashaallah Shamsolvaezin asked for an explanation. The men respondedby threatening him: “If you continue to resist we will take you away by force”.44Abdolfattah Soltani,a well-known human rights lawyer and member of the Centre for HumanRights Defenders, described his arrest in June 2009:“On 16 June, four agents entered my office without having a warrant and showed me a courtorder dated June 10, that is, two days before the election, which had to do with the unrest instreets and had nothing to do with me.”Environmental activist and interpreterMahfarid Mansourian,aged about 46, was arrested fromher home in Tehran in the middle of the night on 7/8 February 2010 by plain clothes officialswho did not identify themselves. Mahfarid Mansourian’s husband, Ghassem Maleki, said theofficials showed her a general arrest warrant which did not specify Mahfarid Mansourian’sname, but which allowed them to arrest anyone “suspicious”. Her whereabouts were unknownfor two days until she telephoned her family and told them she was held in Evin Prison. Shewas released after two weeks.Abdollah Ramazanzadeh, Deputy Chairman of the IIPF, said at the fourth session of the “showtrial” in August 2009 that he had been arrested on the street in June without an arrest warrant.Hengameh Shahidi,an adviser on women’s rights to Mehdi Karroubi (see Chapter 2, Politicalactivists), said that she was arrested on 30 June in the lift of a building where a friend had anoffice. Those who arrested her told her they were security police, but did not show her anyidentification documents. Officials had visited her house several days previously, but she hadnot been at home.Iman Sedighi,a student in Babol (see Chapter 2, Students) arrested fromhis apartment on 18 June 2009, told Amnesty International after his release on bail:“When they took me to [a Ministry of Intelligence] vehicle, they showed me an envelope andtold me: ‘here in this envelope is your arrest warrant’, but they did not show me the content ofthe envelope, therefore contrary to their claim, I did not see any warrant.”

Others have been arrested after being summoned to court.Somayeh Farid,a women’s rightsactivist, was arrested on 16 March after being summoned by phone by court officials. They toldher to go to the Prosecutor’s Office in Evin Prison, to collect some items belonging to herhusband Hojjat (also known as Siavash) Montazeri, who had been arrested on 5 March.Somayeh Farid and her brother-in-law went to the office, but were told that it was closed. On

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

Amnesty International June 2010

24

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

the way home, both were arrested. Her brother-in-law was released shortly afterwards, butSomayeh Farid was not released until 28 March, after payment of bail.A few people have even been detained apparently by sheer coincidence. MohammadOlyaeifard, a human rights lawyer who has defended juvenile offenders and trade unionists (seeChapter 2, Lawyers), was arrested on 1 May to begin serving a one-year prison term. Thesentence had been imposed after he was convicted of “propaganda against the system” forinterviews he gave to foreign media after the execution of his client Behnoud Shojaee, ajuvenile offender who was hanged for a murder he committed when he was 17 years old.45Hislawyer Abdolfattah Soltani said:“Based on the information I have, [Mohammad Olyaeifard] was supposed to meet Mr Azimi, thejudicial assistant of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court. I was supposed to accompany him to themeeting, but I fell ill. I was not able to attend so he went alone. Apparently, as he was going upthe stairs to the meeting office, the head of Branch 26 noticed him and informed him of hissentence. From what I have heard from Mr Olyaeifard’s wife, they handcuffed and shackledhim and sent him to Evin Prison without announcing his verdict to anyone who is able todefend Olyaeifard. Therefore, the verdict and the sentence were not legally communicated tohis lawyers.”46

DETENTION WITHOUT CHARGE OR TRIALThe Iranian Constitution states that “charges with the reasons for accusation must, withoutdelay, be communicated and explained to the accused in writing, and a provisional dossiermust be forwarded to the competent judicial authorities within a maximum of 24 hours”.47TheCode of Criminal Procedure, which reiterates that 24-hour limit,48states that a judge may issuetemporary detention orders for cases involving offences concerning national security, therebyallowing authorities to hold detainees without charge beyond the 24-hour period.49The Codegives the accused the right to appeal against the detention order within 10 days, and althoughit states that the detainee’s case must be resolved within a month, it also allows the judge torenew the temporary detention order.50The Code sets no limits on how many times this ordermay be renewed.The Code of Criminal Procedures says that detainees can petition a judge for release on bail.51It requires that the bail or surety is appropriate and proportionate to the crime and punishmentin question, as well as the status of the accused and his background.52Despite this, bail is often set extremely and disproportionately high, which may force the familyof the detainee to surrender more than one property deed. Many of those arrested since theJune 2009 election have stood bail of amounts equivalent to several hundred thousand USdollars. In some cases, detainees and their families are simply unable to meet such highdemands, and the individual continues to languish in detention.Prisoner of conscienceSayed Ziaoddin Nabavi,amember of the Council to Defend the Right toEducation (see Chapter 2, Rights defenders), is serving a 10-year prison sentence. He remained injail for several months as his family could not meet the bail demanded of 5,000 million rials(approximately US$500,000) to secure his release pending his appeal at which his original 15-yearsentence was reduced to 10 years.Even once a bail order has been issued and judges have issued an order for release on bail, insome cases the detainee has not been released, apparently because one or other intelligencebody refused to comply with the release order. For example,Mohammad Ghouchani,Editor ofthe newspaperEtemad-e Melliwho was detained in June 2009, was not released until October

Amnesty International June 2010

Index: MDE 13/062/2010

From protest to prison: Iran one year after the election

25

2009, some two months after payment of 1,000 million rials (about US$100,000) bail.Kouhyar Goudarzi,a member of the CHRR, remained detained at the time of writing, despite abail order of 700 million rials (reduced from an initial 2,000 million rials) having been madeby a judge, and his family presenting the required amount, because court officials said that hiscase file had gone missing.In other cases, detainees continue to be held even though their temporary arrest warrants haveexpired. In effect, they are being detained without any legal basis.Emadeddin Baghi,aprominent journalist and human rights defender (see Chapter 2, Journalists), was held for twomonths without a valid detention order after his initial two-month temporary detention orderexpired in February 2010. Then, in April 2010, he was brought before a judge and chargedwith a new offence relating to a book he had written 21 years earlier.