Europaudvalget 2011-12

EUU Alm.del Bilag 517

Offentligt

dEtEntIon of MIgRants andasylUM-sEEkERs In CypRUs

Punishmentwithout a crime

amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters,members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaignto end grave abuses of human rights.our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universaldeclaration of human rights and other international human rights standards.we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest orreligion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations.

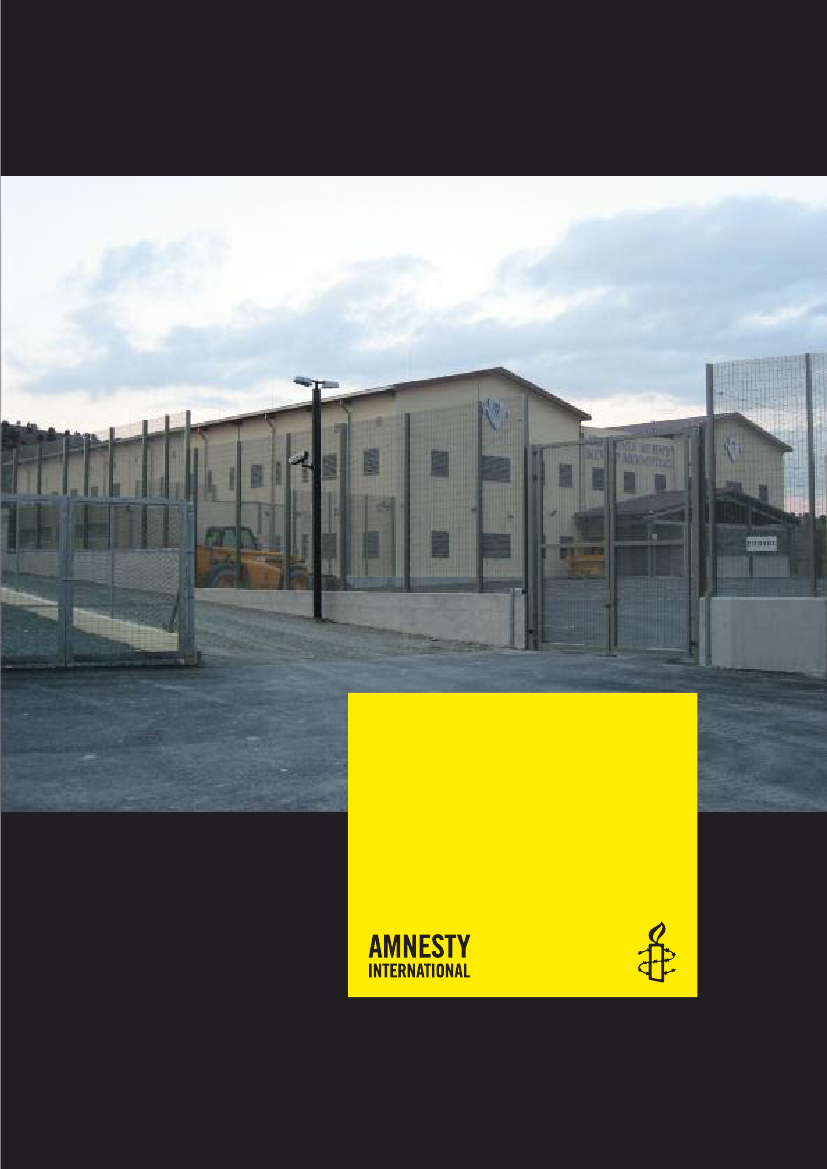

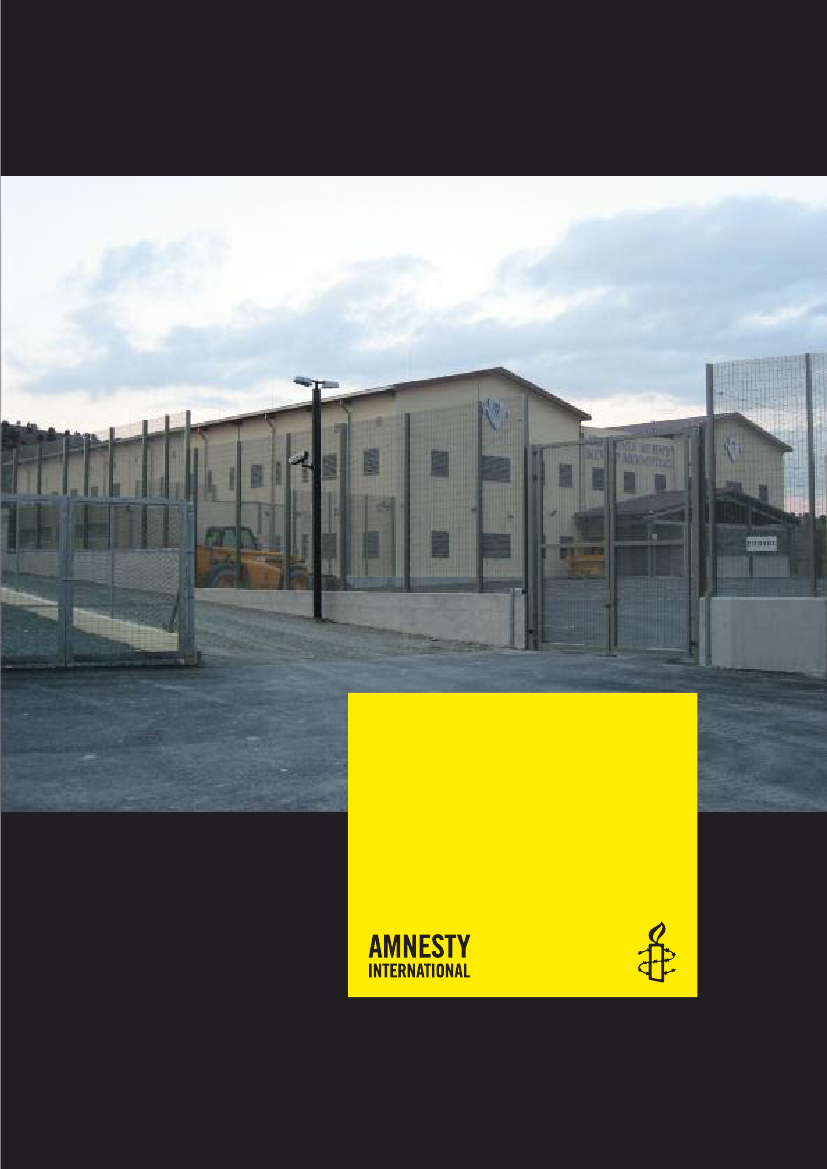

first published in 2012 byamnesty international ltdPeter Benenson house1 easton streetlondon wc1X 0dwunited kingdom� amnesty international 2012index: eur 17/001/2012 englishoriginal language: englishPrinted by amnesty international,international secretariat, united kingdomall rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but maybe reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy,campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale.the copyright holders request that all such use be registeredwith them for impact assessment purposes. for copying inany other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications,or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must beobtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable.to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact[email protected]Cover photo:the menogia detention facility near the southerncity of larnaca, cyprus, expected to become operational in 2012.� amnesty international

amnesty.org

CONTENTS1. Introduction .............................................................................................................3About this report........................................................................................................62. Detention of asylum-seekers.......................................................................................73. Detention of irregular migrants .................................................................................113.1 Failure to examine less coercive measures............................................................123.2 Unaccompanied children migrants and families with children in irregular status.......143.3 Prolonged and repeated detention .......................................................................144. Safeguards against detention inadequate and ignored .................................................174.1 Safeguards against unlawful detention .................................................................174.2 Limited access to free legal assistance.................................................................184.3 Remedies against detention ................................................................................194.4 Effectiveness of remedies challenging detention ...................................................215. Poor detention conditions ........................................................................................226. Conclusions and recommendations ...........................................................................25To the Cypriot authorities .........................................................................................25To EU institutions....................................................................................................27Endnotes………………………………………………………………………………..……………28

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

3

1. INTRODUCTION“They said… they will detain me for another sixmonths and then let me go again for another threemonths. They think this is OK but it is not.”K, an Iranian migrant and mother of three children and whose asylum claim has been dismissed, speaking to AmnestyInternational in January 2012. Amnesty International first met K. in Nicosia Central Prison where she had been detained for fivemonths

Every year, hundreds of people who flee to Cyprus to escape persecution, war or simplygrinding poverty are put behind bars and detained as if they were criminals, even though theyhave committed no crime. Most are detained for months, often in poor conditions withoutaccess to adequate medical care and usually unable to challenge the lawfulness of theirdetention due to the paucity of free legal aid. In some cases, the Cypriot authorities refuse tofree people even when the Supreme Court has ordered their release.Some of those detained have made the difficult decision to flee their homes to find safetyand are exercising their right to apply for asylum and be free from persecution. Pending adecision on their asylum application, they are in an extremely vulnerable position and shouldnot be subject to immigration detention except in the most exceptional circumstances asprescribed by international and regional law and standards.Irregular migrants1too should not be subject to immigration detention and should only bedetained if the detaining authorities can demonstrate that other measures short of detention– including reporting requirements or a surety/guarantor system2– would not be sufficient,consistent with the right to liberty under international human rights law and standards. Whenthe Cypriot authorities detain irregular migrants for immigration purposes withoutdemonstrating that their detention is indeed necessary and that less restrictive measures areinsufficient, they are also violating European Union (EU) law.In the past, many Cypriots were migrants themselves and thousands rebuilt their lives abroadafter becoming displaced during the war of 1974.3More recently, their country has become adestination for migrants and refugees, particularly after Cyprus joined the EU in 2004, manyof whom end up in tough and low-paid jobs, including as agricultural and constructionlabourers and domestic workers. Cyprus is also a destination for trafficking of women forsexual exploitation.Amnesty International recognizes that the Cypriot authorities4face tough challenges becauseof the division of the island. However, whatever the immigration legislation, policies and

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

4

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

practices the Cypriot government chooses to adopt, it must ensure that they comply strictlywith Cyprus’ international legal obligations under human rights and refugee law andstandards, including by promoting and protecting the rights of refugees and migrants.In particular, detaining people when they have committed no crime is a serious breach oftheir fundamental right to liberty. Detention of irregular migrants and asylum-seekers forimmigration purposes is a severe measure that should be used only in exceptionalcircumstances, after careful consideration of the individual case and in full compliance withrelevant international law and standards. The human rights impact of detention is felt notonly by those detained, but also in many cases by their children, spouses and other relativeswho rely on them.Foreign nationals detained in Cyprus for immigration purposes include the following:Irregular migrants or asylum-seekers whose claims have been dismissed and who areheld until their removal/deportation is arranged;Irregular migrants or asylum-seekers whose claims have been dismissed who aredetained for longer periods because their removal cannot be enforced , for example, becausethey have no travel documents and there are difficulties associated in re-documenting them,including instances where the authorities of their country of origin refuse to co-operate withthe re-documentation process; andAsylum-seekers who are detained pending determination of their claim.Moreover, most of those detained languish in detention for long periods, some for over threeyears.Cypriot law does not allow for asylum-seekers to be detained simply for entering the countryirregularly, as long as they apply for asylum without “undue delay” after their arrival andexplain the reasons for their “irregular” entry. However, the Refugee Law provides fordetention ordered by a court on the grounds that:It is necessary to establish the identity or nationality of the person concerned;It is necessary pending the examination of new elements in the application for asylumfiled by an applicant whose initial asylum claim was dismissed and whose deportation hasbeen ordered.5In practice, however, these provisions of the Refugee Law are rarely used and asylum-seekersare much more likely to be detained under the Aliens and Immigration Law provisions (seeChapter 2).Irregular entry and/or stay in Cyprus remain criminal offences. In November 2011, Law153(I)/2011 removed the punishment of imprisonment for the irregular entry into andstaying in the Republic of Cyprus,6but retained the criminal nature of these offences andtheir punishment with a fine (Chapter 3).7However, because the vast majority of irregularmigrants are indigent, Amnesty International is concerned that Law 153(I)/2011 will have alimited impact in reducing the number of those imprisoned in connection with irregular entry

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

5

and/or stay, as most irregular migrants will be unable to pay the fine and will thereforeremain liable to imprisonment. Amnesty International believes that the mere fact ofirregularly entering the Republic of Cyprus and the simple act of remaining in the countryirregularly should not attract criminal sanctions and should be treated purely asadministrative offence, if at all.Law 153(I)/2011 was passed with the aim of transposing “Directive 2008/115/EC of theEuropean Parliament and of the Council on common standards and procedures for returningillegally staying third-country nationals” (the EU Returns Directive).8Amnesty international isconcerned over the failure of Law 153(I)/2011to adequately transpose the provisions of EUReturns Directive especially with regards to the required automatic judicial review of thedecisions to prolong the detention beyond the six months (see chapter 4).Among other things, Law 153(I)/2011 established that a “prohibited immigrant”9whosedeportation has been ordered can only be detained if other less coercive measures do notsuffice and only when detention is necessary for the preparation of the removal and/or tocarry out the removal itself. Those grounds are relevant, in particular, when the individualconcerned presents a risk of absconding or is avoiding or obstructing removal .In addition,the above-mentioned amendments also set limits to the detention periods allowed, providingfor a detention of up to six months which may be prolonged for another twelve months incases where the individual refuses to cooperate or where the reception of the necessarydocuments by the third countries are delayed (see Chapter 3).In practice, the authorities issue detention and deportation orders simultaneously withoutconsidering less restrictive alternatives to immigration detention, and the individualsconcerned are then transferred to the county’s numerous facilities used for immigrationdetention purposes. There are at least nine such facilities – the police stations in Aradippou,Lakatamia, Larnaca, Limassol, Oroklini, and Paphos; Blocks 9 and 10 of Nicosia CentralPrison; and detention facilities at Larnaca International Airport.In all the facilities visited by Amnesty International delegates, asylum-seekers and irregularmigrants are detained in conditions that fall short of international standards. For example,Block 10 of Nicosia Central Prison is a dark and unhealthy facility, with poor natural light,where detainees are forced to spend months in small and often overcrowded cells. InLakatamia and Limassol police stations, detainees have no access to fresh air. In Limassol,immigration detainees have been held in the same wing as people charged with criminaloffences.Everyone – including people whose application for asylum has been dismissed and irregularmigrants – has the right to liberty and security of person, including being free from arbitraryarrest and detention. All states should establish in law a presumption against detention solelyfor immigration control reasons.This report describes how deficiencies in Cypriot law and practice result in the violation ofthe human rights of irregular migrants and asylum-seekers, and includes testimony andexperiences of several people who have suffered as a result.

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

6

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

Among other things, Amnesty International is calling on the Cypriot authorities to:Repeal legislation imposing criminal sanctions for irregular entry or stay, which, shouldbe dealt with, if at all, administratively;End the immigration detention of asylum-seekers;Ensure that other less restrictive alternatives to immigration detention are alwaysconsidered first and given preference before resorting to detention;Ensure that Supreme Court orders to release immigration detainees when their detentionis found to be unlawful are complied with promptly;Ensure that migrants and asylum-seekers are granted effective access to remedies tochallenge detention and deportation orders, including through the assistance of free legal aidand adequate interpretation where necessary.

ABOUT THIS REPORTThis report is based on a research visit to the Republic of Cyprus by Amnesty Internationaldelegates between 28 November and 2 December 2011, as well as other research before andafter that visit. The delegates went to Blocks 9 and 10 of Nicosia Central Prison, as well asLakatamia and Limassol police stations, and interviewed over 100 detainees and staff atthese places as well as people who have been detained there in the recent past. AmnestyInternational is grateful to the Cypriot authorities for facilitating these visits.During the visit the delegates spoke to many people whose asylum claims had beendismissed. While any analysis of asylum determination procedures is beyond the scope of thisreport, Amnesty International has received persistent complaints over the asylum system,including, in particular, about the poor quality of asylum interviews. In this context, AmnestyInternational is also aware of the fact that in 2004 Cyprus was facing a backlog of more than9,000 asylum applications. The organization was made aware that in early 2012 this backloghad been reduced to about 200 cases. The speed with which the Cypriot authorities appearto have dealt with the inordinate backlog, together with the numerous complaints fromindividuals whose claims were dismissed in the course of the clearance exercise, as well asthe exceptionally low recognition rates10, give rise to concerns over the quality of the asylumsystem in Cyprus.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

7

2. DETENTION OF ASYLUM-SEEKERS“I was supposed to be in university this year butthis [detention] has become my university.’’A visibly distressed young Iranian asylum-seeker, speaking to Amnesty International delegates in November 2011. He said he wassupposed to be studying in the university back in Iran and was worried about his mother, who was detained in the next wing, asshe had health problems and was suffering from stress because of the situation of her family

The Refugee Law prohibits the detention of all asylum-seeking children,11and provides thatasylum-seekers who enter or have entered the Republic irregularly should not be detainedsolely for their irregular entry or stay provided that they present themselves without “unduedelay” to the authorities and explain the reasons for their irregular entry.12The law does allowfor a court to order the detention of adult asylum-seekers for up to eight days on two grounds:To establish the applicants’ nationality or identity if they have destroyed or falsified theirpersonal documents and do not reveal their real identity during the submission of theirasylum application; andTo examine new elements in the application after the claim has been refused at theinitial stage and at appeal level and a deportation order has been issued.13A court may extend detention for further eight-day periods up to a maximum total period of32 days.14It appears, however, that in recent years the authorities have not resorted to detainingasylum-seekers under these provisions but instead under those of the Aliens and ImmigrationLaw.15Among asylum-seekers arrested and detained in Cyprus appear to be those who do not file anasylum application before being arrested for irregular entry or stay. The majority of suchpeople appear to be routinely detained regardless of whether they were intending to apply forasylum – even if they have only been in the country for a few days.If an asylum-seeker does present themselves to the authorities within a few days of arrivaland applies for asylum, they are not arrested even if they entered the country irregularly.16Indeed, most asylum-seekers who present themselves to the authorities and apply for asylumweeks or months after arrival are reportedly not arrested and are allowed to file an asylumapplication. However, some have reportedly been arrested for irregular entry and/or stay and –as with those arrested prior to filing an asylum application – have been given a prisonsentence under the Aliens and Immigration Law before the introduction of the legislation

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

8

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

removing the penalty of imprisonment for irregular entry and stay.17After they have served aprison sentence of between three and four months, they have then been issued with anadministrative deportation and immigration detention order. The deportation aspect of theorder is suspended pending examination of the asylum claim, but the asylum-seeker remainsin detention pending the examination of their claim.18Further, some asylum-seekers interviewed by Amnesty International had not been detainedwhen they filed their asylum application, but were subsequently imprisoned for minoroffences and then not released after serving their sentence. Instead, they were transferred tofacilities used for immigration detention purposes under administrative detention anddeportation orders. Such asylum-seekers have their deportation order suspended, but remainin administrative detention during the examination of their claim both at the initial stage andon appeal.19Amnesty International has been made aware of asylum-seekers whose claims have beenrejected at the initial stage and at appeal level, and who have subsequently beenapprehended and remained in detention pending deportation even though they were awaitinga decision by the Supreme Court on their challenge against the rejection of their asylumapplication. This is because an application to the Supreme Court does not automaticallysuspend the deportation process. An application to suspend the deportation, as an interimmeasure must also be lodged with the Supreme Court. The suspension is not grantedautomatically but the applicant needs to establish ‘blatant illegality’ or ‘irreparable damage’.This means that in Cyprus an asylum-seeker may be at risk of forcible return to a place wherethey are at serious risk of human rights violations (breaching the principle ofnon-refoulement)before their claim is finally determined unless the Supreme Court agrees tosuspend the deportation order or in cases where the asylum-seeker has petitioned theEuropean Court of Human Rights. In the latter case, the European Court indicates to theCypriot authorities that “interim measures” (measures that prevent authorities from deportingsomeone to a country where they would not be safe) should be put in place.20

I. is a 25-year-old Pakistani national who arrived in Cyprus in January 2009 to study economics at university.On 2 March 2010 he was arrested because his student visa had expired. He was taken to Block 10 of NicosiaCentral Prison to await deportation. No alternatives to detention were examined. Two weeks after he wasdetained, on 16 March, he applied for asylum, saying that his life would be in danger in Pakistan because hehad filmed an execution by the Taliban.I. was only handed the detention and deportation orders eight months into his detention. His asylum claim wasdismissed at first instance in May 2010 and after appeal in October 2010. On 16 November 2010 an attemptto deport him failed because I. refused to board the plane.On 29 December 2010 his lawyer filed a case to challenge the dismissal of the asylum claim before theSupreme Court. However, the deportation was not suspended. On 14 January 2011 his lawyer submitted ahabeas corpus application before the Supreme Court to challenge the legality of the length of I.’s detention,which by then totalled 10 months. On 20 January 2011 the Supreme Court found the length of his detentionunlawful and ordered his immediate release. However, the next day, and despite the fact that the casechallenging the decision to dismiss his asylum claim was still pending before the Supreme Court, I. wasdeported to Pakistan.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

9

Indeed, Council of Europe guidelines provide that “the remedy against the removal decisionshall have suspensive effect.”21Furthermore, the European Court of Human Rights hasemphasized that:“Only a system of proper review of an asylum request and/or deportationorder with suspensive effect satisfies the needs of legal certainty and protection required insuch matters”.22The Head of Asylum Service, Makis Polydorou, told Amnesty International that applicationsof detained asylum-seekers are prioritized. However, Amnesty International’s delegates foundthat many asylum-seekers languish in detention for several months while their claims arebeing considered, whether they are “prioritized” or not.The Cyprus Commissioner for Administration has expressed concern over the detention ofasylum-seekers while their applications are pending, saying: “… I would like to highlight theproblematic nature of the practice of detaining individuals whose application is pendingbefore the Asylum Service. Asylum-seekers are a particular category of migrants with distinctcharacteristics and for this reason I consider that each case must be treated on its ownmerits’’.23

S. is a 32-year-old Tamil asylum-seeker from Sri Lanka. Even though he had applied for asylum, he spent intotal 16 months in Block 10 of Nicosia Central Prison pending deportation which could not be effected becausehis asylum application was still being considered.He arrived in Cyprus in 2007 to study hotel management and was residing legally on the island. In July 2009,however, after he had heard no news of his family for months following the end of the decades-long conflictbetween the government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, he became desperate forinformation so decided to go to Paris where there is a large Tamil community.24He had no visa for France so heused someone else’s passport to try to leave Cyprus, but was arrested and detained. While awaiting trial, heapplied for asylum given his fears about what was happening to his community in Sri Lanka.In court he admitted his mistake and was sentenced to three months in prison. After he served his sentence,he was immediately taken to a detention centre to await deportation, even though his asylum application wasstill being considered.Thanks to a lawyer who assisted him without charging him, he managed to apply to the Supreme Court to befreed. On 18 January 2011, the Supreme Court ruled that the length of his detention was unlawful and orderedhis release. However, immediately after the ruling, S. was rearrested and detained. He was finally releasedthree months after the Supreme Court order but no document explaining his legal status was given to him orhis lawyer. He told Amnesty International: “A police officer opened the door and told me, ‘go now, you arefree’.” S. has now applied to the Supreme Court for the annulment of the decision rejecting his asylumapplication and remains free, awaiting the Court’s ruling.In addition, case law of the Supreme Court allows for asylum-seekers to be detained incertain circumstances. In particular, the judgment in the case of Asad Mohammed Rahalholds that asylum-seekers are not detained solely for having applied for asylum and thereforetheir detention does not necessarily contravene the Refugee Law. The judgment holds thatdetention is lawful when asylum-seekers breach the provisions of the Aliens and ImmigrationLaw (i.e. irregular entry or stay, or conviction of criminal charges). As such, certain asylum-seekers have been deemed “prohibited migrants” and thus are liable to detention pending

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

10

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

deportation.25. In this respect, the ruling appears to be inconsistent with Article 31 of the1951 Refugee Convention which, in the main, prohibits the detention of asylum-seekerssolely based on their entry or presence in the host country without authorization.The fact that asylum-seekers held in detention as a result of their irregular status are notusually deported until the determination of their claim at the initial stage and on appealindicates that Cypriot authorities do regard them as asylum-seekers whose removal should notbe effected until they are found not to be illegible for international protection. In the light ofthis Amnesty International considers their detention is unnecessary and thus unlawful.Under international law, deprivation of liberty is only lawful if it is in accordance with aprocedure prescribed by law. Any detention related to immigration control is permissible onlyon limited grounds, such as prevention of unauthorized entry into or effecting removal fromthe country.26Detention with a view to enforcing a removal/deportation order and itscontinuance is only lawful where there is a realistic prospect of removal/deportation within areasonable time. In any event, even when the use of detention fulfils these requirements,international standards constrain the resort to detention for immigration control purposes byrequiring its compliance with the principles of necessity and proportionality. This means, forexample, that in each individual case detention will only be justified if less restrictivemeasures have been considered and found to be insufficient with respect to the legitimateobjectives that the state seeks to pursue.27Asylum-seekers – who are presumed to be eligible for international protection unless anduntil proven otherwise following a full, fair and effective asylum determination procedure –should in particular not be detained, either administratively or under any immigration powers,because of their inherent vulnerability.28Human rights bodies have similarly emphasized that detention of asylum-seekers should onlybe a measure of last resort, after other non-custodial alternatives have proven or beendeemed insufficient in relation to the individual. In the case of recognized refugees,detention for immigration purposes should be avoided in all circumstances.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

11

3. DETENTION OF IRREGULARMIGRANTS“I made a mistake and I admit it, but I served mysentence. Why should somebody be punishedtwice?’’D., an Iranian national, speaking to Amnesty International in November 2011 after he had already spent five months in detention.He had been taken into immigration detention immediately after serving a prison sentence imposed for criminal offences

During its visit, Amnesty International found evidence that irregular migrants were beingroutinely detained pending deportation.29Testimonies collected from detainees, lawyers, theoffice of the Commissioner for Administration and NGOs appeared to confirm that the Cypriotauthorities do not consider less restrictive measures before resorting to detention. Rather,detention orders are routinely issued alongside deportation orders. As a result, individuals aretransferred to detention facilities without any prior examination of less restrictive measures.According to the EU Returns Directive, “the use of detention for the purpose of removalshould be limited and subject to the principle of proportionality with regard to the meansused and objectives pursued. Detention is justified only to prepare the return or carry out theremoval process and if the application of less coercive measures would not be sufficient.”30Article 15 includes a number of procedural safeguards to reduce the risk of unlawful orarbitrary detention.Amnesty International considers that there is no lawful justification for the routine detentionof irregular migrants solely for immigration purposes. According to the Aliens andImmigration Law, people considered to be “prohibited immigrants” are not permitted to enteror remain in Cyprus. It defines as “prohibited immigrants”, among others, anyone who hasbeen convicted of a criminal offence for which a prison sentence has been imposed (deemedan “undesirable migrant”) and anyone who enters and stays in the country contrary to theprovisions of the Aliens and Immigration Law.31The same law provides that a “prohibitedimmigrant” may be issued with a deportation order.The same law previously provided that any “prohibited migrant” against whom deportationorders have been issued could be detained pending removal, and no maximum period ofdetention was specified in the relevant article.32However, the Aliens and Immigration Lawwas amended in November 2011 by Law 153(I)/2011 with the intent to transpose the EUReturns Directive. The amendments provided specific requirements before resorting todetention and limits to the detention periods allowed, without however amending or

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

12

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

abolishing the existing provisions that allow for the detention of irregular migrants pendingtheir deportation.33Lawyers told Amnesty International that the authorities continue today toissue orders under the older article of the Aliens and Immigration Law.34

K. fled her native Iran in 2003, leaving behind one of her two children, and arrived in Cyprus the following year.On arrival, she immediately applied for asylum for herself and the daughter she had been able to travel with.The application was rejected at initial stage and on appeal. In 2008, she married N, a recognized refugee inCyprus, and later that year the couple had a daughter. K. and N. were married in a mosque, but the authoritiesdo not recognize their marriage.In August 2011, while K. was at a local market, the police arrested her and placed her immediately indetention because her documents were not in order. No alternative to detention was considered. “No oneseemed to care that a three-year-old girl was waiting for me back home,’’ she said.Amnesty International met her in November 2011 in Block 9 of Nicosia Central Prison, where she had spentfive months in total. She said: “My child she thinks her mother abandoned her and has many psychologicalproblems as a result of being separated from her mother. Nobody cares, nobody wants to help us.’’K.’s older daughter is now 24 and has lived in Cyprus since she was 15. She speaks Greek and English butshe is scared to leave the house fearing that she will be arrested and detained like her mother. “She wants togo to university,” her mother said, “but instead she is imprisoned in her own house’’.In January 2012, the authorities released K. provisionally and gave her three months to get her papers in orderand re-marry N. in the town hall. However, town hall officials told her that she needed a valid passport. Toobtain one, the Iranian embassy requires a birth certificate which she cannot get in time. She also claims thatthe authorities have her original birth certificate, handed to them when filed her asylum application, but so farrefuse to return it despite her lawyer’s efforts.She said: “Last time I went to the immigration authorities they told me to not worry, they said that when myconditional release period is over, they will detain me for another six months and then let me go again foranother three months. They think this is OK but it is not. What will happen to my kids?’’

3.1 FAILURE TO EXAMINE LESS COERCIVE MEASURESAmendments introduced by Law 153(I)/2011 seeking to transpose the EU Returns Directiveset certain grounds that need to be met before resorting to detention.Apart from some exemptions, the legislation provides for between a week and 30 days inwhich the individual may leave “voluntarily”, during which enforcement action, includingdetention, is not envisaged.35If the person does not leave “voluntarily”, the Director of theCivil Registry and Migration Department may take all necessary measures to enforce theorder, including the use of coercive measures, albeit only as a last resort. These measuresshould be proportionate, and any coercion should be reasonable in the circumstances.36Law 153(I)/2011 provides that the Minister of Interior may issue a detention order unless, ina given case, other sufficient but less coercive measures can be applied effectively. Such anorder may be issued to a third country national subject to removal procedures only to preparethe return and/or carry out the removal process of the individual, in particular when the

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

13

person presents a risk of absconding or is avoiding or obstructing the return or removalprocedure''.37The law, however, does not specify any alternative and less coercive measures.Despite the legislation transposing the provisions of the Returns Directive providing for priorexamination of less coercive measures before resorting to detention, the organization’sresearch points to the fact that in practise these provisions are disregarded.Amnesty International’s delegates met several individuals who had been issued withdetention and deportation orders. Some had served a prison sentence for irregular entryand/or stay and then been immediately redetained for immigration purposes and transferreddirectly from prison to a facility used for immigration detention purposes.The majority of those detained during Amnesty International’s visit were irregular migrantsawaiting deportation. Many had initially been living legally in Cyprus but had then violatedthe terms of their visa, for example by overstaying, taking up work they were not allowed todo, or working more hours than their student visa permitted. Some of those detained awaitingremoval had been convicted of criminal offences and been sentenced to short prisonsentences of three to four months. In all these cases, their detention appeared routine, withno prior examination of any alternative less restrictive measures. Many had no prospect ofbeing removed from Cyprus within a reasonable time. As a result, their detention appearedarbitrary and unnecessary – and therefore unlawful under both Cypriot and EU law.Many testimonies confirmed that the authorities continue to detain individuals even thoughthey cannot be deported because of a lack of travel documents. Some detainees told AmnestyInternational that they had been detained several times pending deportation, each timespending varying periods in detention, in some cases reaching a total of three or four years.The Commissioner for Administration, in a letter to the Minister of Interior, expressedconcern over the detention of individuals pending their removal before examining lesscoercive measures, especially in view of the country’s obligations under the EU ReturnsDirective. She noted that it was “clear that the measure of detention should only be used asa last resort, after other less coercive measures have been examined and dismissed”.38The resort to detention without prior examination of less coercive measures contravenesCypriot law39as well as international standards, which provide that detention is only justifiedif less restrictive measures have been considered and found to be insufficient. The samestandards are set out in the EU Returns Directive which also requires the release of anindividual whose removal cannot be carried out within a reasonable time and for whom thereare no other immigration detention grounds.Further, as set out in paragraph 16 of the preamble to EU Returns Directive, “the use ofdetention for the purpose of removal should be limited and subject to the principle ofproportionality with regard to the means used and objectives pursued. Detention is justifiedonly to prepare the return or carry out the removal process and if the application of lesscoercive measures would not be sufficient.” Article 15 of the Directive requires, among otherthings, that in order to be detained the individual must be subject to return procedures.

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

14

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

3.2 UNACCOMPANIED CHILDREN MIGRANTS AND FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN INIRREGULAR STATUSAmnesty International delegates did not come across any children detained for migrationpurposes during their visit. While urging the government to pursue its policy of refrainingfrom detaining children for immigration purposes, the organization is concerned that therecent legislation, reflecting the provisions of the EU Returns Directive, fails to abolish thedetention of unaccompanied migrant children. In particular, it allows for unaccompaniedmigrant children and migrant families with children to be detained as a last resort and for theshortest possible period. It also specifies that unaccompanied migrant children, to the extentpossible, will be accommodated in institutions where personnel and facilities are appropriateto the needs of minors and that the best interests of the child will be the primaryconsideration40.In relation to the detention of families with children for immigration purposes, the Cypriotauthorities recently reported to the United Nations (UN) Committee for the Rights of theChild that children could not stay with their parents in police detention facilities and for thatreason a parent was released to allow for unification and childcare.41However, NGOs andlawyers told Amnesty International of cases where both of the parents are detained pendingtheir deportation and the children are placed under the care of welfare services. AmnestyInternational is further concerned over the stated intention of the Cypriot authorities to theUN Committee for the Rights of the Child that children will be able to be detained with theirfamily in a special family block once the new detention facility in Menogia becomesoperational.Amnesty International believes that there should be a prohibition in law on detention ofunaccompanied children solely for immigration purposes. Children, and in particularunaccompanied or separated children, should never be detained solely for immigrationpurposes given that immigration detention cannot be said to be in their best interests, ever.The detention of children solely for immigration purposes, whether they are unaccompanied,separated or held together with their family members, can never be justified and representsan abject failure of the obligation to respect, care for, and protect children’s human rights42.In cases involving the detention of asylum-seeking children and other children solely forimmigration purposes, the European Court of Human Rights has rightly emphasised theextreme vulnerability of such children, in particular but not exclusively unaccompanied orseparated children43. It should be noted that the Court not only found the detention of thesechildren in violation of Article 5 of the ECHR (i.e. the right to liberty and security of person)but also that it amounted to a violation of Article 3 of the ECHR (i.e. freedom from tortureand inhuman or degrading treatment).

3.3 PROLONGED AND REPEATED DETENTIONDuring their visit, Amnesty International delegates met a number of people who had beendetained for several months, some for over a year. Many of those held for immigration reasonsare caught in a vicious circle. While there is no reasonable prospect of enforcing theirremoval, they spent several months in detention after their initial arrest for irregular entry/orstay, then they were released and redetained a few months or years later for immigrationreasons as they had no means of regularizing their status.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

15

Delegates met individuals who had spent in total three or four years in detention as a resultof such practices.Moreover, during Amnesty International’s visit, detainees and NGOs expressed concern aboutthe stringent and arbitrary release procedures being applied at that time in relation toirregular migrants who could not be deported. Similarly, the Commissioner for Administrationnoted: ‘’As a result, I note that the conditions imposed must in any case be clear andtransparent and be explained in writing to the individual concerned in a way that they areunderstood by him/her. In any case, conditions imposed must be practicable and should notrequire actions that are not reasonably feasible’’.44Amnesty International’s delegates saw the devastating effect that prolonged and unlawfuldetention had on mental and physical health. Detainees had difficulty with focusing andremembering key dates, and demonstrated signs of anxiety and stress, including scars causedby self-harming. The delegates were told that in the months before their visit, some suchdetainees had attempted suicide and one had died as a result.

When Amnesty International delegates met Z., an Iranian asylum-seeker whose claim had been dismissed, hehad already been detained for three months and before that had been detained for three consecutive years. InApril 2012, he remained in detention. The office of the Commissioner for Administration has repeatedly raisedconcern over the lawfulness of Z.’s detention given that his deportation had not been feasible for the pastthree years due to the lack of travel documents and the fact that, to date, there is no realistic prospect ofdeporting him.45Law 153(I)/2011 sets the maximum length of detention pending deportation at six months,with the possibility of extending it for a further 12 months in certain circumstances.46It alsoprovides that detention shall be as short as possible and only maintained as long as removalarrangements are in progress and carried out with due diligence.47Prior to the amendmentsintroduced by Law 153(I) 2011, no maximum period of such detention was specified.48These maximum lengths of detention are the same as those provided in the EU ReturnsDirective. Indeed, the Returns Directive also allows extensions up to 12 months in addition tothe initial six-month period if the individual concerned is not co-operating with the removalprocess or if there are delays in obtaining necessary documentation from third countries.49Ifa reasonable prospect of removal no longer exists, then detention ceases to be justified andthose detained must be released immediately. Amnesty International cautions that, albeitpermissible under EU legislation, detaining someone solely for immigration purposes for upto 18 months is incompatible with the right to liberty as recognized in the EuropeanConvention on Human Rights and in other international human rights instruments by whichCyprus is bound.

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

16

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

X. is evidently anxious due to the fact that it is unknown to her when her mother willreturn home and why she is today detained. The absence of her mother appears to affecther everyday life, her activities and in general the functioning of the family, resulting inX. being overwhelmed by stress and agony for the future as well as melancholy , aphenomenon that can seriously disturb the personality of a child.Specialist’s assessment of the impact on a child whose mother had been detained for months in one of Cyprus’ detentionimmigration facilities, in October 2011

In summary, Amnesty International believes that the implementation of law, policy andpractice regarding the detention of irregular migrants pending deportation breaches relevantEU and international standards and is resulting in grave human rights violations.Amnesty International believes that if detention occurs, it should always be for the shortestpossible time and must not be prolonged or indefinite. Once the maximum period fordetention has expired, the individual concerned should be automatically released.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

17

4. SAFEGUARDS AGAINST DETENTIONINADEQUATE AND IGNORED“What kind of country separates a mother fromher child?”N., an asylum-seeker from Sri Lanka, speaking to Amnesty International in November 2011

A series of obstacles impedes people’s ability to access justice and challenge effectively theirdetention for immigration purposes in Cyprus.

4.1 SAFEGUARDS AGAINST UNLAWFUL DETENTIONLaw 153(I)/2011 states that the detention of a third-country national for the purposes ofremoval must be ordered in writing and accompanied by a reasoned justification of thematerial and legal grounds.50It also provides that the Minister of Interior informsimmediately the person concerned about their right to file an application before the SupremeCourt requesting the annulment of the detention order or a habeas corpus applicationchallenging the lawfulness of the length of detention. However, the Minister is not obliged toinform the person of their right to a review of the detention order through an application tohim/her. Legislation also fails to explicitly state that information about such remedies mustbe provided in writing in a language that the third country national understands.

N. is an asylum-seeker from Sri Lanka. She is married to another Sri Lankan asylum-seeker who lives in Cyprusand they have submitted a family asylum application. They have an eight-year-old daughter.In September 2011, N. was arrested without documents and detained in Block 9 of Nicosia Central Prison.Michalis Paraskevas, her lawyer, told Amnesty International that despite his repeated requests, the authoritiesdid not provide him with the deportation and detention order, so in April he challenged the lawfulness of herdetention before the Supreme Court.When Amnesty International met N. in December 2011, she was still in detention along with several otherwomen held pending deportation. She tearfully said: “What kind of country separates a mother from her child?Yesterday it was her birthday. My daughter told me, ‘mama I miss you so much’.’’N. was eventually released on 23 April 2012, one day before the scheduled Supreme Court hearing and afterseven months in detention.Amnesty International has documented several cases attesting to a failure by the policeauthorities to explain to immigration detainees the reasons for their detention, its possible

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

18

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

length and the rights to which they are entitled whilst in immigration detention. Detaineesand their lawyers told Amnesty International that often they are not provided with the reasonsand justification of detention. Usually, detainees are given a short letter simply referring tothe legislative provisions under which their detention has been ordered and to the fact thatthey are being detained pending deportation. In some cases, deportation and detentionorders were handed to the individuals concerned several months into their detention.Such shortcomings are particularly common in relation to detained asylum-seekers. A largenumber interviewed by Amnesty International, particularly those whose applications werepending, did not appear to know how long they would be detained, even when they wereaware of its grounds.While in immigration detention facilities, Amnesty International delegates did not comeacross any materials, such as leaflets in different languages, informing detainees of theirrights and ways to challenge detention, nor was a list of lawyers readily available.International human rights standards guarantee the right to be informed of the reasons fordetention.51The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention stated in Deliberation No. 5 thatnotification of the detention must be given by the authorities in writing, in a languageunderstood by the asylum-seeker or migrant, stating the grounds for the measure and settingout the conditions under which those detained must be able to apply for a remedy to ajudicial authority.52

4.2 LIMITED ACCESS TO FREE LEGAL ASSISTANCEImmigration detainees have very limited access to free legal aid. National legislation does notprovide for free legal aid to challenge an administrative detention order or, until recently, tochallenge a deportation order.According to the authorities, the detainees, with the cooperation of the immigration office,have the right to apply for legal assistance and the appointment of a lawyer during theproceedings before the Courts regarding the deportation and detention decisions.53In February 2012, Legal Aid Law 165(I) of 2002 was amended and now provides for freelegal aid to irregular migrants in order to contest any removal decision or entry ban. However,such free legal assistance is limited to proceedings at first instance before the SupremeCourt under Article 146 of the Constitution54and is granted only if the appeal is deemed tohave a reasonable chance of success.55Moreover, it is up to the applicant, who at that pointis not entitled to free legal aid, to argue the likelihood of success. NGOs and lawyers toldAmnesty International that the authorities do not inform detainees of this possibility.Only a few lawyers provide free services to asylum-seekers and irregular migrants wishing tochallenge their detention. KISA, a Cypriot NGO, had been providing free legal aid to migrantsand asylum-seekers but at the time of Amnesty International’s visit had ceased operationsdue to a lack of resources.International human rights standards, including the UN Body of Principles for the Protectionof All Persons under Any Form of Detention or Imprisonment, guarantee the right of access tolegal counsel and the right to legal assistance and interpretation for asylum-seekers and

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

19

irregular migrants who have been detained. Article 47 of the EU Charter of FundamentalRights further stipulates that: “Everyone whose rights and freedoms guaranteed by the law ofthe Union… shall have the possibility of being advised, defended and represented. Legal aidshall be made available to those who lack sufficient resources in so far as such aid isnecessary to ensure effective access to justice”. The EU Returns Directive provides that “thenecessary legal assistance and/or representation is granted on request free of charge inaccordance with relevant national legislation...’’56Moreover, in a 2008 case against Turkey concerning two detained Iranian UNHCR-mandatedrefugees, the European Court of Human Rights found a violation of Article 5.2 of theEuropean Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) on account of the applicants being deniedlegal assistance and not being informed of their grounds of their detention.57In a 2010 caseagainst Greece concerning a detained asylum-seeker, the Court held that the existing remedyagainst his detention was purely theoretical on account of the lack of access to free legalassistance.58The Court found a violation of Article 5.4.Navigating the legal system of administrative detention for immigration purposes in Cyprus isnot a realistic expectation for the vast majority of detained irregular migrants and asylum-seekers, especially when there is such limited access to free legal assistance.

4.3 REMEDIES AGAINST DETENTIONCypriot legislation provides two avenues to challenge before a court the lawfulness of adetention solely for immigration purposes. Firstly, Law 153(I)/2011 provides for a challengeunder Article 146 of the Constitution before the Supreme Court59. If successful, this resultsin the annulment of the detention order. The same law also allows for a habeas corpusapplication under Article 155.4 of the Constitution before the Supreme Court challenging thelawfulness of detention on length grounds.60According to lawyers, the average length of recourse under article 146 of the Constitution isone and a half years whereas in a habeas corpus application is one or two months. In thecase of an appeal against an unsuccessful application, the length of the appeal proceedingsin both cases is about 5 years in average.In addition, according to domestic legislation, the Minister of Interior reviews immigrationdetention orders either on his/her own initiative every two months, or at a reasonable timefollowing an application by the detainee.61The Minister is also solely responsible for anydecision to prolong detention for an additional maximum period of 12 months.However, the lack of automatic judicial review of the decision to detain is a cause of majorconcern. Each decision to detain should be automatically and regularly reviewed as to itslawfulness, necessity and proportionality by a court or similar competent independent andimpartial body, accompanied by the adequate provision of legal aid.Article 5(4) of the ECHR provides that “everyone who is deprived of his liberty by arrest ordetention shall be entitled to take proceedings by which the lawfulness of his detention shallbe decided speedily by a court and his release ordered if the detention is not lawful”. Article18(2) of the Asylum Procedures Directive states: “where an applicant for asylum is held indetention, Member States shall ensure that there is a possibility of a speedy judicial review”.

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

20

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

Article 15(2) of the EU Returns Directive stipulates that: “when detention has been orderedby administrative authorities, Member States shall: (a) either provide for a speedy judicialreview of the lawfulness of detention to be decided as speedily as possible from thebeginning of detention; (b) or grant the third-country national concerned the right to takeproceedings by means of which the lawfulness of detention shall be subject to speedyjudicial review to be decided as speedily as possible... In such a case Member States shallimmediately inform the third-country national concerned about the possibility of taking suchproceedings.” Article 15(3) states that: “In every case, detention shall be reviewed atreasonable intervals of time either on application by the third-country national concerned orex officio. In case of prolonged detention periods, reviews shall be subject to the supervisionof a judicial body”.In the light of these standards, and because of the lack of an automatic judicial review of theadministrative orders to detain, especially in the cases of prolonged detention, it is clear thatthe procedural safeguards in Cypriot law fall short of international and regional standardsincluding the EU Returns Directive.

O., a Sierra Leonean whose claim was dismissed, arrived in Cyprus in 2001 when he was around 30 years old.Amnesty International delegates met him in the dingy and cramped Block 10 of Nicosia Central Prison, wherehe showed them a folder marked “evidence”. He said: ‘’I prepared it in case someone showed up.’’He explained that he had fled Sierra Leone as a result of events arising from the decade-long civil war in thecountry. In 2004 the Cypriot authorities closed his file, saying that they could not locate him to examine hisapplication. He refutes that claim, saying that he was forced to change address and informed the authoritiespromptly.A few months later, in February 2005, he was arrested. Over most of the next three years he was held in Block10 during which four failed deportation attempts took place. In one of these attempts, in December 2005,immigration officers escorted him to Ghana but the authorities there refused to allow them to proceed to SierraLeone due to lack of proper documentation.Amnesty International had already met him in detention in 2007 and had written to the Cypriot authorities toraise concern about the lawfulness and length of his detention. He was eventually released for the first time inMay 2008, after 39 months in continuous detention. He told Amnesty International that upon release he wasleft destitute and without any legal status. “The guard just opened the doors and told me ‘go now’. No papers,nothing. What was I supposed to do, where was I supposed to go?’’He was eventually forced to take up work to survive and as a result was arrested again in October 2010 for“illegal stay and employment” and again detained pending deportation. In August 2011, after he had beendetained for around 10 months, he challenged the lawfulness of his detention on the grounds of its protractedlength before the Supreme Court. He won and the court ordered his immediate release. However, before he leftthe court premises he was arrested and detained once again. The new arrest order was dated one day beforethe Supreme Court judgment was issued.His faith in justice was shattered, he said. He added that when he arrived in Cyprus, “I was tricked bysmugglers to believe I was safely in a EU country [Cyprus only joined the EU in 2004]. For months I thought Iwas in Greece. Now I have been tricked again, this time by the authorities. What is there left for me to do?’’

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

21

He was finally deported to Sierra Leone in January 2012, having spent in total more than four years indetention in Cyprus.

4.4 EFFECTIVENESS OF REMEDIES CHALLENGING DETENTIONAmnesty International is particularly alarmed by cases in which successful challenges againstimmigration detention have been mounted by way of habeas corpus applications have not ledto the release of the detainees concerned, as ordered by the Supreme Court, or release hashappened only after considerable delay.62The Supreme Court found in these cases that the continuation of detention beyond sixmonths was unlawful and ordered the individual’s immediate release. However, theapplicants were instead rearrested before leaving the Supreme Court building or immediatelyafter on the basis of new detention orders issued on the same grounds.63In at least one suchcase, the new detention order predated the Supreme Court’s decision by a day. Cypriotlegislation provides for immediate release of any third-country national if their applicationunder Article 154.4 of the Constitution is successful.64

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

22

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

5. POOR DETENTION CONDITIONS“The doctor who comes here says there is nothinghe can do for me and sends me away.”B., a Nigerian asylum-seeker whose claim has been refused, speaking to Amnesty International in detention in November 2011

Amnesty International’s delegates visited Blocks 9 and 10 of Nicosia Central Prison, andLakatamia and Limassol police stations, all of which are used to detain asylum-seekers andmigrants pending deportation. The organization is deeply concerned about the poorconditions witnessed and considers that they fall short of international standards.65Moreover,the facilities used to detain irregular migrants and asylum-seekers are not purpose-builtfacilities but police stations and two wings of the Nicosia Central Prison.The Cypriot Authorities claim that over the past years new police detention facilities havebeen constructed, in accordance with international standards, and improvements were madeto the existing facilities to meet those standards.66Moreover, during the organization’s visit,members of staff told Amnesty International that they provide the detainees with adequatemedical care including the necessary medication and also facilitate the exercise of thereligious needs of the detainees.However, when visiting Block 10 of the Nicosia Central Prison, delegates came across poorconditions. Cells were often overcrowded, had inadequate access to natural light, were poorlyventilated and some had broken windows. The sanitary facilities were dirty and most toiletshad no doors. Inmates said that they were allowed only for a very limited time to exerciseoutside.I have serious problems back in Iran but I’d rather risk it and go back than stay in hereany longer.Iranian national whose asylum application had been rejected, referring to conditions in Block 10 of Nicosia Central Prison

The two police stations were set up to hold people only for short periods, but insteaddetainees were being kept there for months. Neither had open space for exercise or access tofresh air. In Limassol, people charged with criminal offences were being detained in thesame wing.None of the facilities visited had a resident doctor and Amnesty International’s delegatesheard many complaints about a lack of adequate medical care. Detainees said that guardsdecided whether or not they needed to see a doctor or required hospital treatment. Inmatesalso complained about the poor quality of food. None of the facilities had a space forreligious worship or recreation areas.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

23

B. is a 36-year-old Nigerian who arrived in Cyprus in 2005 and applied for asylum. His application wasrejected but he says that he was never interviewed. When Amnesty International met him in December 2011,he had been detained in Block 10 for over four months and had no idea what would happen to him. He hadnever seen a lawyer because he was unable to pay for one.He told Amnesty International that his eyes were causing him problems and that his eyesight had seriouslydeteriorated in detention. “My eyes swell up and I can’t sleep for days,’’ he said. “The doctor who comes heresays there is nothing he can do for me and sends me away. He only gives Panadol [a painkiller] to everyoneanyway – we call him Panadol doctor.’’67B.’s documents show that he was taken to the hospital three timesbut he claims it was only twice. He was diagnosed with a chronic problem but was only given eye drops “thathave no effect’’. He fears he will lose his sight.“All the difficulties people experience here are 10 times worse for me because of my sight problems,’’ he said.“It takes me 10 minutes to get to the toilet. It feels like torture.’’During the visit, delegates also heard allegations of ill-treatment. Such allegations were alsoreceived prior to the visit. In particular, in July 2011, about 35 police officers reportedlybeat, threatened and verbally abused a group of asylum-seekers detained in Larnaca policestation. One of the asylum-seekers was said to have suffered leg injuries and to have beendenied medical assistance for several days. Investigations into the incident by the office ofthe Commissioner for Administration and police complaints’ authority were pending at theend of 2011.In October 2011, asylum-seekers and irregular migrants were reported to have staged ahunger strike in Block 10 of Nicosia Central Prison and Larnaca police station to protestagainst the conditions and their prolonged detention.

A. comes from sub-Saharan Africa. When Amnesty International met him in Block 10 of Nicosia Central Prisonhe had already been detained for more than a month pending deportation. After his asylum claim was rejectedin 2009, he was advised to pursue the case further but he said that he could not afford a lawyer.A. has diabetes and said that since his detention he had lost a considerable amount of weight. “With thenutrition here it is impossible to follow a proper diet,’’ he said. He also told Amnesty International that thevisiting doctor had never checked his blood sugar level. He has his own monitoring machine, but needs specialneedles for it work. When they ran out, he asked for replacements, but the ones they brought him were notcompatible with his machine. “When I asked for proper needles I was mocked by the guards,’’ he said. “Theytold me to pay for them myself but I have no money.”During a meeting with Amnesty International on 30 November 2011, the then Minister forInterior acknowledged “shortcomings” in the conditions of detention. He said that a newimmigration detention centre was about to open in the Menogeia region and that conditionsthere would meet international standards. At the time of writing in May 2012, however, thecentre had yet to become operational. Amnesty International notes that even if the planneddetention facilities meet international standards, immigration detention for removal purposesshould only be resorted to in exceptional circumstances, and in compliance with theprinciples of necessity and proportionality.

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

24

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

Law 163(I)/2005 provides that all detainees have the right not to be subjected to torture andinhuman or degrading treatment or any other physical or psychological violence. It states thatthose responsible for a detention facility shall ensure adequate and appropriate nutrition,physical and mental health, hygiene, safety and physical integrity of the detainees.68International human rights standards such as Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civiland Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 3 of the ECHR prohibit torture, cruel, inhuman ordegrading treatment. Article 10 (1) of the ICCPR stipulates that “all persons deprived of theirliberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the humanperson”.Article 16(1) of the EU Returns Directive states that detention will as a rule be in specializedfacilities and if this cannot be provided and third-country nationals are detained in prisons,they should be kept separately from ordinary prisoners. Article 16(3) of the Directivestipulates that: “particular attention shall be paid to the situation of vulnerable persons” andArticle 14(1)(b) states that: “emergency health care and essential treatment of illness areprovided”.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

25

6. CONCLUSIONS ANDRECOMMENDATIONSThe routine detention of irregular migrants and of a large number of asylum-seekers clearlyviolates Cyprus’ human rights obligations. This pattern of abuse is partly due to inadequatelegislation, but more often it is down to the practice of the authorities, particularly when itcomes to their failure to examine real alternatives to immigration detention and theirdisregard of Supreme Court orders to release detainees. Urgent action is needed to rectifythis situation that results in serious violations of the human rights of asylum-seekers andmigrants. Speedy implementation of the recommendations outlined below would go some waytowards ensuring the respect and protection of the rights of irregular migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus.To the Cypriot authorities

On criminalization of irregular entry and stayRepeal legislation that criminalizes irregular entry or stay.

On detention of asylum-seekersEnd the detention of asylum-seekers for immigration purposes in law and in practice, inline with international human rights standards which require that such detention is only usedin exceptional circumstances;Ensure that the recourse to the Supreme Court regarding a decision rejecting an asylumapplication at the initial stage or at appeal level automatically suspends the implementationof a deportation order.

On detention of irregular migrantsEnsure that other less restrictive alternatives to detention are always considered first andgiven preference before resorting to detention. Alternatives to detention must be realalternatives to detention, as opposed to alternative forms of detention. In any event, theirimposition must also strictly comply with the necessity and proportionality requirements;Detention should only be lawfully used when the authorities can demonstrate in eachindividual case that alternatives will not be effective and that it is necessary andproportionate to achieve a legitimate objective.

On detention of unaccompanied asylum-seeking and migrant childrenProhibit in law the immigration detention of unaccompanied migrant and asylum-seekingchildren.

On the decision to detain and length of detentionEnsure that the decision to detain is automatically reviewed by a judicial bodyperiodically on the basis of clear legislative criteria;

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

26

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

Ensure that migrants and asylum-seekers deprived of their liberty are promptly informedin a language they understand, in writing, of the reasons for their detention, of the availableappeal mechanisms and of the regulations of the facility. The decision to detain must entailreasoned grounds with reference to law and fact;Immediately release immigration detainees for whom the sole basis of detention is theirremoval when this cannot be implemented within a reasonable time;Ensure that detention is always for the shortest possible time;Ensure that the maximum duration for detention provided in law is reasonable.

Procedural safeguards and access to informationEnsure that migrants and asylum-seekers are granted effective access to remediesagainst administrative detention and deportation orders, including through the assistance offree legal aid to challenge detention and/or deportation and adequate interpretation wherenecessary;Ensure that deportation procedures contain adequate procedural safeguards, includingthe ability to challenge individually the decision to deport, access to competent interpretationservices and legal counsel, and access to appeal before a judge;Ensure that migrants and asylum-seekers in detention are accurately informed about thestatus of their case and of their rights to contact a consular or embassy representative and ormembers of their families. Migrants and their lawyers should have full and complete accessto the migrants’ files;Ensure that consular authorities are only contacted if this is requested by the detainedmigrant; asylum-seekers should not be brought to the attention of their consular authoritieswithout their knowledge and consent;Facilitate migrants’ and asylum-seekers’ exercise of their rights, including by providingthem with lists of lawyers offering free services and telephone numbers of consulates andorganizations providing assistance to detainees;

On effectiveness of remediesEnsure that Supreme Court orders to release detainees when their detention is found tobe unlawful are complied with immediately.

On detention conditionsEnsure that conditions for migrants and asylum-seekers held in immigration detentionconform to international and regional human rights standards, including the UN Body ofPrinciples for the Protection of All Persons under Any Form of Detention and the UNStandard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners;Ensure that irregular migrants and asylum-seekers held for immigration-related purposesare detained in purpose-built facilities that are not punitive in nature and are separated fromcriminal detainees;

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

27

Ensure provision of proper medical examination as promptly as possible and of medicaltreatment, including psychological counselling where appropriate, whenever necessary andfree of charge;Ensure that detained migrants and asylum-seekers have access to interpreters in theircontacts with doctors or when requesting medical attention;Ensure that detainees have access to appropriate educational, cultural and informationalMaterial;Ensure that a separate bed with clean bedding and personal hygiene products areprovided for each detainee and that detainees have at least one hour of outdoor exercisedaily;Conduct prompt, impartial and comprehensive investigations into all allegations of ill-treatment and torture of refugees, asylum-seekers and irregular migrants by law enforcementofficials.To EU institutionsAmnesty International recommends that the European Commission fully and thoroughlyinvestigate the extent to which Cyprus’ laws and practices comply with the EU asylum andimmigrationacquisand in accordance with its powers initiates infringement proceedingsbefore the Court of Justice of the European Union where necessary.

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

Amnesty International June 2012

28

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

ENDNOTES1

For the purposes of this report, the term irregular migrant is used to refer to a foreign national who

lacks legal status in Cyprus – be it a transit or host country for the person concerned; one who enteredCyprus without authorization, or entered the country legally but then lost permission to remain in thecountry. Another term used is undocumented migrant.2

Reporting requirement is a periodic reporting to state officials, in person or by phone. A ‘’surety’’ is the

guarantee given by the third person that the individual will comply with the immigration procedures; tothis end, the third person, the ‘’guarantor’’, agrees to pay a set amount of money if the individualabsconds. SeeReport of the Special Rapporteur on human rights of migrants,A/HRC/20/24, 2 April2012.3

Following an invasion by Turkish troops in 1974, the island was divided into a territory controlled by

the authorities of the internationally unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and a territorycontrolled by the authorities of the Republic of Cyprus. These territories lie respectively north and southof the “Green Line”, a buffer zone controlled by the UN, which has been stationed on the island sincethe eruption of inter-ethnic hostilities in 1964.4

For the purposes of this report, the term “Cypriot authorities” refers to the government of the Republic

of Cyprus.56

Refugee Law 6(I)/2000, Article 7(4)(a).Until November 2011, these offences were punishable by imprisonment or a fine or both (Aliens and

Immigration Law, Cap.105, Article 19).78

Law 153(I)/2011 Article 18 OΓ (2).Directive 2008/115/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on

common standards and procedures for Member States returning illegally staying third-country nationals.9

Cypriot law defines a “prohibited immigrant” as anyone who has been given a prison sentence for a

criminal offence or anyone who enters or stays in the country in breach of the Aliens and ImmigrationLaw.10

According to the National Asylum Authority, in 2010, only in 11 out of 2,371 asylum applications

examined by the Asylum Service were granted refugee status; in 2011, it was only 28 out of 2,455. In2010, subsidiary protection was granted in 214 cases; in 2011 in one case.1112131415

Refugee Law 6(I)/2000, Article 7(4)(c).Refugee Law 6(I)/2000, Article 7(1).Refugee Law 6(I)/2000, Article 7(4)(b).Refugee Law 6(I)/2000, Article 7(6).Interview with Corina Drousiotou, legal advisor with Future Worlds Center which is implementing a

UNHCR programme providing legal aid to asylum-seekers; and interview with the office of theCommissioner for Administration, 15 April 2012.

Amnesty International June 2012

Index: EUR 17/001/2012

PUNISHMENT WITHOUT A CRIMEDetention of migrants and asylum-seekers in Cyprus

29

16

According to the office of the Commissioner for Administration and NGOs working with asylum-seekers

in Cyprus.1718

Law 153(I)/2011, Article 18 OΓ (2).Interview with the office of the Commissioner for Administration office, 15 April 2012, and confirmed

by the interview with Corina Drousiotou.1920

According to NGOs and lawyers interviewed by Amnesty International.“Interim measures”, as spelled out by European Court of Human Rights under Rule 39 of the Rules of

Court, require a state party to refrain from removing an applicant to a country where he or she may be atreal risk of a violation of his or her fundamental rights.Amnesty International has raised concerns overthe non-suspensive effect of that recourse in Cyprus. SeeAmnesty International: State of the world’shuman rights 2011.21

Council of Europe Guidelines on human rights protection in the context of accelerated asylum

procedures, Guideline X.222324

M.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece,Judgment of 21 January 2011 (Application no. 30696/09).Letter to the Minister of Interior, File no. A/Π 1786/2011, 2 December 2011.Hundreds of thousands of Tamil civilians were arbitrarily detained in military-run camps in Vavuniya

district at the end of the war. See Amnesty International, ‘’Unlock the Camps in Sri Lanka: Safety anddignity for the displaced now’’ (AI Index AS/37/016/2009).25

Asad Mohammed Rahal v Republic of Cyprus, Judgement of 30 December 2004 (Application no.

1023/2004).2627

See, for example, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Article 5(1)(f).See relevant UN Human Rights Committee jurisprudence on Article 9 of the International Covenant on

Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR);A v. Australia,Communication No. 560/1993;C v. Australia,Communication No. 900/1999. See also Council of Europe Guidelines on human rights protection in thecontext of accelerated asylum procedures, Guideline XI.28

The European Court of Human Rights has also emphasized the inherent vulnerability of asylum-

seekers. SeeM.S.S. v. Belgium and Greece, Judgment of 21 January 2011 (Application no. 30696/09).29