Europaudvalget 2012-13

EUU Alm.del Bilag 497

Offentligt

27 September 2012

Eighteenth Bi-annual Report:Developments in European UnionProcedures and PracticesRelevant to Parliamentary Scrutiny

Prepared by the COSAC Secretariat and presented to:XLVIII Conference of Parliamentary Committeesfor Union Affairs of Parliamentsof the European Union14-16 October 2012Nicosia

Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairsof Parliaments of the European UnionCOSAC SECRETARIATWIE 05 U 041, 30-50 rue Wiertz, B-1047 Brussels, BelgiumE-mail: [email protected] | Tel: +32 2 284 3776

ii

Table of ContentsBACKGROUND........................................................................................................................... ivABSTRACT.................................................................................................................................. 1CHAPTER 1: RELATIONS BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS AND NATIONALPARLIAMENTS............................................................................................................................ 31.1 Subsidiarity and proportionality........................................................................................ 31.1.1 The principles of subsidiarity and proportionality...................................................... 31.1.2 Proportionality and national Parliament scrutiny....................................................... 51.1.3 Reasoned Opinions.................................................................................................... 71.1.4 Guidelines.................................................................................................................. 81.2 The political dialogue........................................................................................................ 91.2.1 Activity under the political dialogue......................................................................... 101.2.2. Presentation of the Commission Work Programme (CWP)......................................101.2.3. Frequency of presentation of specific proposals in Parliaments by the Commission111.2.4. Strengthening the political dialogue with European institutions..............................12CHAPTER 2: THE TREATY ON STABILITY, COORDINATION AND GOVERNANCE IN THEECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION AND THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTS....................................162.1 Ratification of the TSCG.............................................................................................. 162.2. Reinforcement of Interparliamentary co-operation on the basis of the role assigned tonational Parliaments by Article 13 of the TSCG................................................................. 172.3 Appropriate forum for the discussion of budgetary policies and other issues asstipulated by Article 13 of the TSCG..................................................................................172.4 Composition of the forum...........................................................................................19CHAPTER 3: ENERGY - TRANS EUROPEAN ENERGY INFRASTRUCTURE.......................................203.1 Parliamentary scrutiny of the proposal....................................................................... 203.2 Specific questions considered in scrutiny.................................................................... 223.3 Content of contributions and parliamentary documents.............................................23CHAPTER 4: SINGLE MARKET GOVERNANCE............................................................................. 254.1 Parliamentary scrutiny of Single Market governance.................................................. 25

iii

BACKGROUNDThis is the Eighteenth Bi-annual Report from the COSAC Secretariat.COSAC Bi-annual ReportsThe XXX COSAC decided that the COSAC Secretariat should producefactual Bi-annual Reports, to be published ahead of each ordinary meetingof the Conference. The purpose of the Reports is to give an overview ofthe developments in procedures and practices in the European Union thatare relevant to parliamentary scrutiny.All the Bi-annual Reports are available on the COSAC website at:http://www.cosac.eu/en/documents/biannual/The four chapters of this Bi-annual Report are based on information provided by the nationalParliaments of the European Union Member States and the European Parliament. The deadlinefor submitting replies to the questionnaire for the 18th Bi-annual Report was 27 August 2012.The outline of this Report was adopted by the meeting of the Chairpersons of COSAC, held on 9July 2012 in Limassol.As a general rule, the Report does not specify all Parliaments or Chambers whose case isrelevant for each point. Instead, illustrative examples are used.A summary of answers can be found in the appendix to the Report and complete replies,received from all 40 national Parliaments/Chambers of 27 Member States and the EuropeanParliament, can be found in the Annex on the COSAC website.Note on NumbersOf the 27 Member States of the European Union, 14 have a unicameralParliament and 13 have a bicameral Parliament. Due to this combination ofunicameral and bicameral systems, there are 40 national parliamentaryChambers in the 27 Member States of the European Union.Although they have bicameral systems, the national Parliaments of Austria,Ireland and Spain each submitted a single set of replies to the questionnaire.

iv

ABSTRACTCHAPTER 1: RELATIONS BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS AND NATIONALPARLIAMENTSOn the subject of subsidiarity and proportionality, their relative standing and their use in thenational Parliament scrutiny processes, Parliaments/Chambers expressed varied views andexchanged much valuable information. Parliaments/Chambers are split into two broadlydistinctive views on the issues for and against the arguments that subsidiarity andproportionality are of the same standing and that proportionality is an inextricablecomponent of subsidiarity. However, it can be seen that almost all Parliaments/Chambersconsider the principle of proportionality when scrutinising draft legislative acts in general.On the subject of subsidiarity checks, there was a mixed response to the question of howoften proportionality criteria are currently considered within these checks, with some usingthese criteria rarely or sometimes and a few more doing so often or always. There was,however, a majority of Parliaments/Chambers who stated that they do not believe thatsubsidiarity checks are effective without the inclusion of a proportionality check.On further working together, half of Parliaments/Chambers stated that there is the need forfurther clarification of the subsidiarity check criteria used by national Parliaments andChambers/Parliaments were almost equally divided as to whether guidelines should be laiddown to improve the effectiveness of subsidiarity checks.On the political dialogue, the majority of Parliaments/Chambers have undertaken some formof political dialogue, mostly written opinions. However, the majority also stated that suchpolitical dialogue could be strengthened or enhanced and advanced a number of ways ofimproving it. In general, Parliaments/Chambers would welcome more prompt andsubstantive responses by the Commission to concerns raised by them.The majority of Parliaments/Chambers have never had a discussion with a Commissioner orCommission staff on the Commission's Work programme. However, there is evidence ofsignificant and frequent contact between the Commission and/or its staff on specificCommission proposals and Parliaments/Chambers would welcome more visits andparticularly with a tailored approach by Commissioners adapted to the needs of eachParliament/Chamber.Parliaments/Chambers were, in general, in favour of closer and more frequent contacts withother Parliaments/Chambers and the Commission in respect of proposals that raise particularconcerns and for which a large number of reasoned Opinions were issued. The means forsuch contacts are highlighted in the Report.

1

CHAPTER 2: THE TREATY ON STABILITY, COORDINATION AND GOVERNANCE IN THEECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION AND THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTSOn the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic and MonetaryUnion, most Parliaments/Chambers reported that the ratification document for the TSCG hasnot yet been deposited, but, indicated that, during the second half of the year 2012, theratification procedure would proceed. Concerning the reinforcement of interparliamentaryco-operation as stipulated by Article 13 of the TSCG, Parliaments/Chambers emphasised thatArticle 13 provides a platform for closer co-operation. With regards to the appropriate forumand its composition, it seems that there have been, as exemplified in the Report, varyingviews and that more discussion should be expected on this matter in the future.CHAPTER 3: ENERGY - TRANS EUROPEAN ENERGY INFRASTRUCTUREOn trans-European energy infrastructure, the replies to the questions in this chapter showthat two thirds of Parliaments/Chambers scrutinised the above mentioned proposal whileone third chose not to do so. Of those Parliaments/Chambers that scrutinised the abovementioned proposal two thirds were in favour and one third partly in favour of its objectives;none were against. However, several national Parliaments expressed selective concernsover various specific aspects of the above proposal which are documented in this Report.It can be deducted from Parliaments'/Chambers' replies that future inter-parliamentarydiscussions on the substance of the proposal could revolve around questions linked to thefunding, the allocation of EU support, the distribution of investment costs, the level ofcontrol by the Commission over the direction of projects and the role for Member States, theworking patterns of regional groups the regulatory treatment and the eligibility of projects ofcommon interest and the design of permit planning procedures as well as the pros and consof the much earlier consultation and broader basis for involvement of the general public.CHAPTER 4: SINGLE MARKET GOVERNANCEImplementation and transposition of European Union legislation is receiving more and moreattention as it is an area that could be more effective and might lead to substantial costsavings. This is also to be seen with national Parliaments' scrutiny where almost half of theParliaments/Chambers answered that they had either already considered the CommissionCommunication on better governance for the Single Market or expressed intentions to do soin the near future. The findings of that scrutiny have been summarised in the Report.

2

CHAPTER 1: RELATIONS BETWEEN THE EUROPEAN INSTITUTIONS ANDNATIONAL PARLIAMENTSThe first chapter of the 18th Bi-annual Report of COSAC examines two different aspects ofrelations between the European Institutions and national Parliaments. The chapter istherefore divided into two sections. The first section concentrates on the principles ofsubsidiarity and proportionality and their application by Parliaments in the scrutiny process,including the procedure for checking subsidiarity. The second section takes stock of activitytaking place under the umbrella of the political dialogue and examines how it may be furtherenhanced.1.1 Subsidiarity and proportionalitySubsidiarity and proportionality are principles that have underpinned the actions of theEuropean Union since its creation and have equally attracted scrutiny from nationalParliaments. Since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty (Treaty on the European Union orTEU), however, new light has been shone on the examination of the subsidiarity andproportionality by national Parliaments, particularly due to the Protocol (No 2) on theapplication of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.The aims of section 1.1 of the 18thBi-annual Report are to document the opinions of nationalParliaments on the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality, their relative standing andtheir use in the national Parliament scrutiny processes, including a part on ReasonedOpinions. The section also aims to examine the question of the effectiveness of subsidiaritychecks (without the inclusion of proportionality) and the usefulness of guidelines aimed toimprove them.1.1.1 The principles of subsidiarity and proportionalityThe Lisbon Treaty in Article 5(3) TEU describes theprinciple of subsidiaritythus "in areaswhich do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Union shall act only if and insofar asthe objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States,either at central level or at regional and local level, but can rather, by reason of the scale oreffects of the proposed action, be better achieved at Union level." It goes on in Article 5(4)TEU to describe theprinciple of proportionalitythus "the content and form of Union actionshall not exceed what is necessary to achieve the objectives of the Treaties". Both Articlesstate that the principles should be applied in accordance with Protocol 2 of the Treaty. ThisProtocol calls for the European institutions "to ensure constant respect" for the principles aslaid down in Article 5 and sets out a procedure for national Parliaments to check the principleof subsidiarity.In the replies to the questionnaire sent to all Parliaments/Chambers to gather their views,responsesas to whether the principles of proportionality and subsidiarity have the samestandingwere divided between yes and no. Of the 39 responding Parliaments/Chambers 18answered that they believed that the two principles were of equal standing, whereas 21 didnot. Many Parliaments/Chambers quoted Article 5 TEU as the justification for the twoprinciples being given the same standing. For instance, the SpanishCortes Generalesreplied3

that in Article 5 "both principles...govern the use of Union competences, and...areaccordingly jointly regulated in Protocol 2" which reflects the equal importance given toboth. The CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponargued that the Treaty of Lisbon provisions torespect both principles in Article 5 should be applied in Protocol 2 and therefore this was "aclear indication that a subsidiarity check should also include a proportionality check" and thatthe two principles have the same standing. The GermanBundestagchecks both principlestogether due to the difficultly of separating the concepts and believes they enjoy the samestanding. Likewise, the DutchEerste Kamerchecks the legal basis, the principle of subsidiarityand the principle of proportionality together and believes all three are interlinked. Accordingto the HungarianOrszággyűlés,which also agreed that both principles have the samestanding, said that the "clear political character" of national Parliaments' analysis was shapedby "national and regional considerations as well as party interests." The FrenchAssembléenationaleargued that the principle of proportionality brought a "more thorough andnuanced approach" to the scrutiny of EU legislative acts.A number of those who replied that the two principles formally have the same standingacknowledged, however, that in practice this is not the case. The UKHouse of Lordsexplained that "because the Reasoned Opinion procedure applies only to subsidiarity, theprinciple receives greater focus". The SwedishRiksdagput forward a similar view. The FinnishEduskuntaalso commented that the concepts of subsidiarity and proportionality "seem tohave been reduced to academic issues - or a formal justification" because the use ofProtocols 1 and 2 has developed into "a vehicle for expressing political opinions".Some 15, of the Parliaments/Chambers that answered yes in this case also said that theythought that theprinciple of proportionality should be considered an inextricablecomponent of the principle of subsidiarity.In addition the AustrianNationalratandBundesrat1argued that "measures taken by the EU may only go as far as is necessary toachieve a legitimate goal. Measures going beyond this point are without doubt reserved tothe Member States. The compliance with the principle of subsidiarity therefore necessarilyinvolves a proportionality check". The BelgianChambre des représentantsexplained that"logically, the proportionality check precedes the subsidiarity control as the first step to solvea problem is to determine the appropriate action (= proportionality)". The DutchEersteKamerstated that it considers proportionality "as a component of the subsidiarity test" whilethe CzechPoslanecká sněmovnastated its view that they are “of equal importance” and“complementary”.Almost all of those 21Parliaments/Chambers who argued that the principles of subsidiarityand proportionality do not have the same standing,explained that this is becauseParliaments/Chambers are not given a formal right to check proportionality under the LisbonTreaty which they are afforded for subsidiarity under Protocol 2. The fact that “[l]egallyspeaking the principle of proportionality is excluded from the subsidiarity check” (DanishFolketing)and the consequent lack of ability to legally check proportionality, they argued,meant that proportionality does not receive the same standing as subsidiarity. Some note thealternative non-legal route to raise concerns about proportionality through the informalpolitical dialogue between national Parliaments and the EU institutions. The European1

Governing majority SPÖ (S&D) and ÖVP (EPP) parties

4

Parliament replied that "[i]t is up to the European Court of Justice to interpret the standing ofthe two principles."2Many (some 16) of these Parliaments/Chambers also answered no to the question ofwhether the principle of proportionality is considered an inextricable component of theprinciple of subsidiarity.For example, the PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicastatedcategorically that "the two principles are clearly different and neither can be subsumed in theother" and explained that the principle of subsidiarity ensured that legislation is adopted atthe most appropriate decision-making level, while the principle of proportionality related tothe content and form. The LatvianSaeimawas equally clear that the principles "are twodifferent principles of EU law" and Protocol 2 stipulates a procedure "for detection only ofthe subsidiarity principle". The UKHouse of Commonsused the following analogy: "ifproportionality is looking at whether a sledgehammer can be used to crack a nut, subsidiarityis looking at whether the sledgehammer should be picked up in the first place."The opinion of the UKHouse of Lords,who responded that the two principles should beapplied separately "since they regulate different aspects of a proposal", was also shared bythe IrishHouses of the Oireachtasand the SlovenianDržavni zbor.The PolishSenatreferenced the Great Britain vs Council case (C-84/94)3as clearly stating that subsidiarity andproportionality are independent of each other. In line with this, the PolishSejmfound someacts to infringe the principle of proportionality without violating the principle of subsidiarity.A few Parliaments/Chambers acknowledged that the principles are applied or consideredseparately, though expressed regret that this is the case (e.g. BulgarianNarodno sabranieand ItalianSenato della Repubblica).The European Parliament did not express an opinion about whether the two principles areinextricably linked but explained that "The question to be asked in the application of theprinciple of proportionality is...up to which intensity can the Union exercise its competence(which it is authorised to exercise following a positive subsidiarity test)?" and made the pointthat "[s]ubsidiarity applies only in cases of shared competence, whereas proportionalityapplies also where the Union enjoys exclusive competence."1.1.2 Proportionality and national Parliament scrutinyOut of 41 national Parliaments/Chambers, a large majority of 37 Parliaments/Chambersconsider the principle of proportionality when scrutinising draft legislative actsand onlyfour do not. This indicates that national Parliaments' general scrutiny goes well beyondsimply checking the principle of subsidiarity, even though many acknowledged that the latteris the only formal power given to national Parliaments under the Lisbon Treaty. It can also beseen that some national Parliaments consider the legal basis or principle of conferral (e.g.ItalianSenato della Repubblicaand PolishSejm),as well as proportionality and subsidiarity(and this can be all at the same time, e.g. CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon).For example theDutchEerste Kamerstated that it "always check proportionality when checking subsidiarity"and states "it is not possible to exclude the principles of legality."2

All replies transmitted by the European Parliament to the Secretariat of COSAC are replies prepared by itsadministration and do not engage the Institution politically.3For the text of the full judgement please see:http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:61994CJ0084:EN:HTML

5

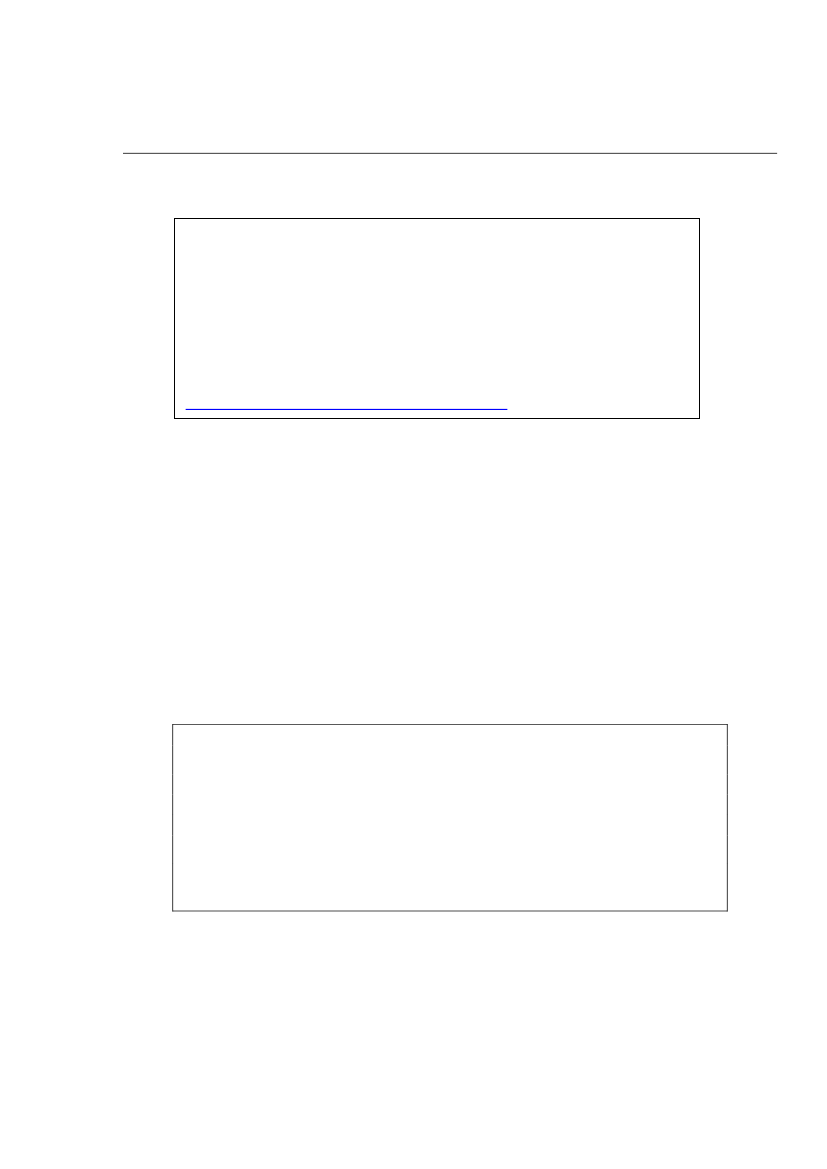

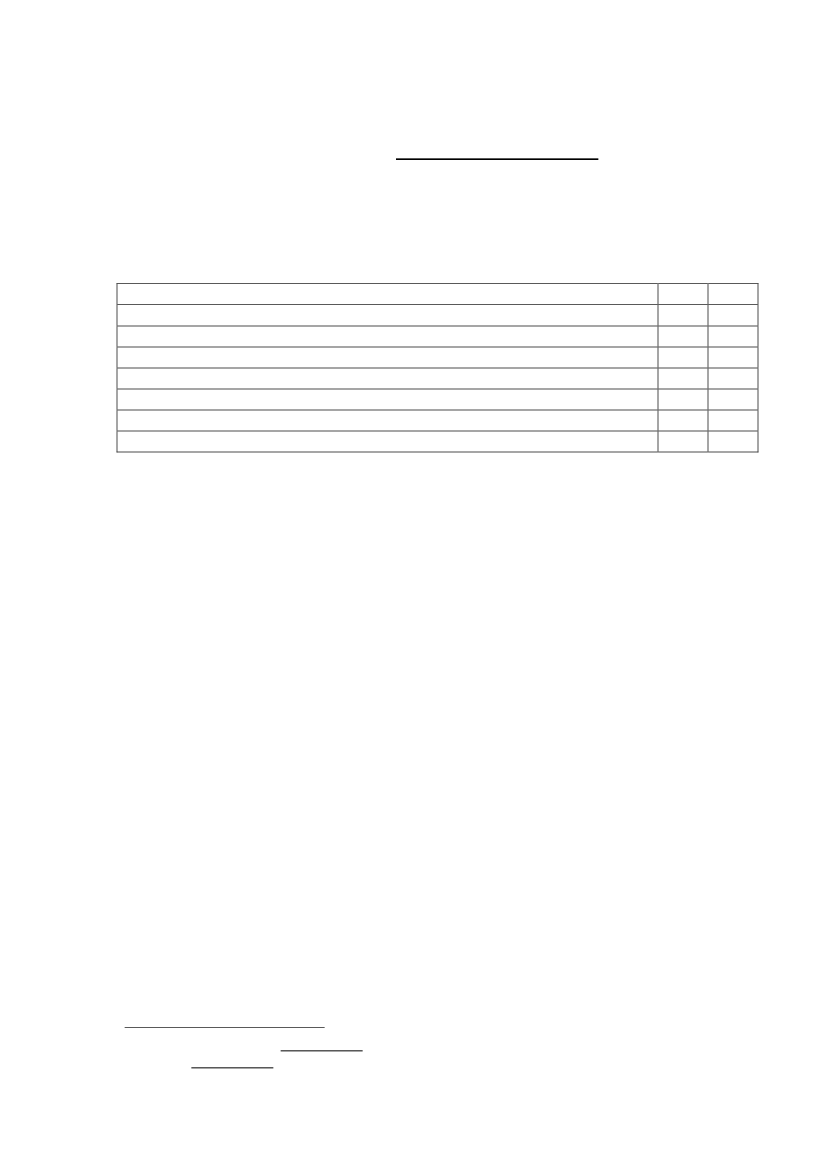

In contrast, however, there was a mixed response to the question ofhow oftenproportionality criteria are considered as part of subsidiarity checks.It appears that, in linewith the arguments made for and against the two principles having the same standing and/orbeing inextricably linked above, the responses from national Parliaments spanned fromnever, rarely or sometimes (a total of 12 Parliaments/Chambers) to often or always (a total of20 Parliaments/Chambers). The specific responses to this question can be seen in the tablebelow:Responses4NeverRarely (approximately a quarter of the time)Sometimes (approximately half of the time)Often (approximately three quarters of the time)AlwaysOtherTotal number of respondents%8158153520No.363614840

Interestingly, however, a large majority of 28 Parliaments/Chambers stated that they do notbelieve that subsidiarity checks are effective without theinclusion of a proportionalitycheck.Many of these Parliaments/Chambers argued that including proportionality criteria inthe subsidiarity check would be positive. The LatviaSeimasexplained its view that in order toevaluate subsidiarity, i.e. to judge whether the proposal is the most effective way to solve aproblem, it is necessary to check proportionality, i.e. to judge whether the proposal solvesthe problem at all. Another reason given was that the strict separation of the principles ofsubsidiarity and proportionality could undermine the effectiveness of the subsidiarity checkbecause it was not always discernable on what grounds the breach had occurred (CzechSenát).Many argued along the same lines as the UKHouse of Lordswho said simply that "theprinciples are applied by the Treaties and they are closely linked". The PolishSenatrepliedthat "national Parliaments’ limited power to scrutinise subsidiarity compliance should beextended to include also the scrutiny of EU legislation for its compliance with proportionalityprinciple". The PolishSejmargued for it to go further and for national Parliaments to be ableto legally scrutinise the application of all the principles that are also mentioned in Article 5TEU. In the opinion of the CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon,an exclusion of the proportionalitycheck posed "an unnecessary restriction to the broadness of a subsidiarity check" and "wouldlimit the rights vested to national Parliaments under the Lisbon Treaty". Others suggestedthat the inclusion of proportionality principle in the subsidiarity check procedure would be"logical", "helpful", "preferable" and "more effective". According to the DutchTweede Kamer“[t]he separation of these principles ... has always been unnatural and not logical”.Of the 11 Parliaments/Chambers that answered that the check was effective withoutincluding proportionality, a number continued to make the converse point to those abovethat, because subsidiarity and proportionality are separate concepts and have a different4

Where "No." indicates the actual number of Parliaments/Chambers who responded and percentage (%) is theratio of the actual number of responses to the total number of respondents.

6

standing under the EU Treaties, they could effectively only be considered separately fromeach other (e.g. FinnishEduskunta,MalteseKamra tad-Deputatiand UKHouse of Commons).1.1.3 Reasoned OpinionsA large majority of 28 Parliaments/Chambers agreed with the statement thatReasonedOpinions (ROs)are often based on a broader interpretation of subsidiarity than the wordingof Protocol 2 of the Lisbon Treaty and nine disagreed. A number of Parliaments/Chambers, inexplaining their responses, said that the interpretation of subsidiarity should be strictlylimited to the legal basis under Protocol 2 of the Treaty. However, most of the respondentsindicated that they thought that it was appropriate for there to be a broader or widerinterpretation of subsidiarity. The DutchEerste Kamersaid that "it is not possible to excludethe principles of legality and proportionality when applying a subsidiarity check...Thus Article6 (and onwards) should be applied in the spirit and working of the preceding articles and theTitle of Protocol 2". The CzechSenátreplied that subsidiarity has a “general and abstractnature…is not a strict and clear legal concept” and therefore argued that a broadinterpretation should be used. The UKHouse of Lordssaid that it did not have difficulty withthe use of a wider interpretation because, “[a]lthough the principle is a legal concept, inpractice its application depends on political judgment”. The BelgianChambre desreprésentantsalso viewed the content of Reasoned Opinions as a political matter. TheFinnishEduskuntawent as far as to say that “[i]n our assessment, hardly any of the ROssubmitted by national Parliaments meet the requirements of Art 5 TEU” citing its own RO tothe Monti II legislation as a case in point.5The MalteseKamra tad-Deputatiargued that“since no uniform definition of subsidiarity exists, Parliaments could be interpreting itdifferently and consequently using different criteria”. The SwedishRiksdagreplied that it hadsubmitted ROs based on a broader interpretation of the principle of subsidiarity and theirchecks, in certain cases, had included an assessment of the principles of proportionality aswell as legality.6The ItalianSenato della Repubblicanoted that "the restricted notion of subsidiarity...is moreadherent to the provisions of the treaties...[while] a broader notion, including the scrutiny ofthe legal basis (principle of conferral) and proportionality compliance...seems to be differentfrom the formal provisions of the treaties". The European Parliament replied that it "does notassess the admissibility of the reasons given by national Parliaments with a view toconcluding or not that a draft legislative act does not comply with the principle ofsubsidiarity."Given the mixture of opinions on the inclusion of the principle of proportionality in ROs, it isnot altogether surprising that 20 out of 40 of Parliaments/Chambers believe that there is theneed forfurther clarification of the subsidiarity check criteriaused by national Parliamentsand an equal number do not. Comments by those who wanted further clarification includedthe following:

5

Reasoned Opinion by the FinnishEduskuntaon the Monti II Regulation COM (2012) 130http://www.ipex.eu/IPEXL-WEB/scrutiny/APP20120064/fiedu.do6e.g. COM(2010) 486, COM(2011) 634, COM(2010) 799 and COM(2012) 130

7

criteria would be useful but should not be compulsory (PolishSenat)and beyondbasic criteria national Parliaments should be left to deal with subsidiarity in their ownway (CzechSenát);criteria should bring clarification regarding what should and should not be included inor excluded from a Reasoned Opinion (CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon)or whatbreaches the principle of subsidiarity (MalteseKamra tad-Deputati)or could include aset of questions aimed to determine non-compliance (LatvianSaeima);exchange of information and best practices within COSAC on the criteria, methodsand tools for assessment of the subsidiarity principles (ItalianCamera dei Deputati);the focus should be on technical and formal criteria as laid down by the Lisbon Treaty(HungarianOrszággyűlés)or, as this was not possible in the view of the BulgarianNarodno sabranie,on the old protocol on the application of the principles ofsubsidiarity and proportionality (1997) - Protocol (30) to the Treaty establishing theEuropean Community provides a better ground for the subsidiarity checks;consideration should be given to collecting all contributions and articles relating tosubsidiarity check and to distributing electronically to COSAC participants or to postsuch information on the COSAC website and all official positions of EU Institutionsaiming at clarifying the procedure should also be distributed or posted (ItalianSenatodella Repubblica);it may be of value to have access to a comment to the Treaty or a table containing allthe legal bases in the treaties (article by article) and whether or not protocol 2 shouldbe applicable to each of them. Such a table could be drafted jointly by the legalservices of the Council, the Commission and the Parliament in cooperation with thenational Parliaments (SwedishRiksdag);andseminars on how to approach the assessment of subsidiarity criteria would be useful(UKHouse of Commons)or conferences, workshops, seminars with the participationof MPs and their staff (LithuanianSeimas).

1.1.4 GuidelinesJust over half (20 out of 37 respondents) expressed the view thatguidelinesshould be laiddown to improve the effectiveness of subsidiarity checks and the otherParliaments/Chambers were against such a move. When those who answered positivelywere asked about what these guidelines should contain, answers included:specific guidelines regarding the scope of the negative reasoned opinions (HungarianOrszággyűlés);guidelines on the drawing up of reasoned opinions would be welcome as this wouldbring about a degree of uniformity (MalteseKamra tad-Deputati);the exchange of best practice on procedures (LithuanianSeimas)and jointexperiences in different countries (SwedishRiksdag);the scope and content of reasoned opinions, with the possibility of laying downguidelines (UKHouse of Commons);a clear explanation of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality - like that usedin the recent Reasoned Opinion of the UKHouse of Commonson the Right to takecollective action contains under point 6 a clear and useful explanation of subsidiarity.Especially the quote under 6 ‘The Community shall legislate only to the extentnecessary’ is meaningful; this regards both subsidiarity and proportionality. The8

guidelines could also be used to exchange good practices among nationalParliaments. (DutchTweede Kamer);andsuch guidelines should fully clarify the principles of subsidiarity and proportionalityand their interpretations (BelgianChambre des représentants).

The AustrianNationalratandBundesrat7suggested that discussion on this topic of guidelinesshould take place in the forum of COSAC.Those 17 Parliaments/Chambers that were against the idea of guidelines being laid down toimprove the effectiveness of subsidiarity checks included the FinnishEduskuntawho "wouldstrongly oppose any such proposal" going as far as to say "this cannot and should not beshackled by any extraneous rules" and the PolishSenatwho suggested that a set of criteriashould be used "not on a compulsory basis". The IrishHouses of the Oireachtasstated that"[a]s subsidiarity is difficult to define and strict guidelines may impinge on the autonomy ofnational Parliaments, [it] feels that sharing of best practice between national Parliaments isthe best way forward". The FrenchAssemblée nationalealso expressed some doubt as to amore precise definition of subsidiarity which would lead to limiting national Parliaments'margin of appreciation in the context of what it calls a "political dimension" of subsidiaritycontrol. On a similar note, the DutchEerste Kamersaid it would be open to discussions, butwas not in favour of a clarification that entails a restriction of the interpretation ofsubsidiarity check criteria.To summarise this section, Parliaments/Chambers are split into two broadly distinctive viewson the issues for and against the arguments that subsidiarity and proportionality are of thesame standing and that proportionality is an inextricable component of subsidiarity.However, it can be seen that almost all Parliaments/Chambers consider the principle ofproportionality when scrutinising draft legislative acts in general.On the subject of subsidiarity checks, there was a mixed response to the question of howoften proportionality criteria are currently considered within these checks, with some usingthese criteria rarely or sometimes and a few more doing so often or always. There was,however, a majority of Parliaments/Chambers who stated that they do not believe thatsubsidiarity checks are effective without the inclusion of a proportionality check.On further working together, half of Parliaments/Chambers stated that there is the need forfurther clarification of the subsidiarity check criteria used by national Parliaments andChambers/Parliaments were almost equally divided as to whether guidelines should be laiddown to improve the effectiveness of subsidiarity checks.

1.2 The political dialogueThe concept of political dialogue was launched by European Commission President Barroso in2006.8It is a general term referring to a range of ways to improve communication between7

Governing majority SPÖ (S&D) and ÖVP (EPP) parties

9

national Parliaments and the European Commission. Since its launch the use of politicaldialogue has evolved and greatly intensified and has given national Parliaments a greatervoice and role in independently shaping and influencing EU affairs.The aims of section 1.2 of the Bi-annual Report are to exchange information and to seek todocument the activity that is currently taking place under the political dialogue. This part willexamine the current state of play of the political dialogue, showing how it has evolved overthe last six years, and how it might be further enhanced.1.2.1 Activity under the political dialogueThere are many developments to report given that the majority of Parliaments/Chambershave undertaken some form ofpolitical dialogue.According to the answers byParliaments/Chambers to the questionnaire, 30 parliaments/Chambers have sent writtenopinions to the Commission while some 25 have had other contacts with the Commission orbilateral visits to or from European institutions.911 Parliaments/Chambers cited examples ofother forms of activity they viewed as part of the political dialogue which included:the hosting by the Commission of study visits for national Parliament staff on topicsrelated to new economic governance and the financial markets (the ItalianSenatodella Repubblica);pre-legislative consultation by the Commission on specific proposals, for example, theinformal meeting between national Parliaments and DG Home Affairs concerning theparliamentary control of Europol in April 2012 (CzechPoslanecká sněmovna);meetings between parliamentary committees and national MEPs (the FrenchSénatand GermanBundestag);andthe organisation of technical briefings for Members of Parliament by EuropeanCommission staff on a very regular basis (DutchTweede Kamer).Despite undertaking this type of activity some Parliaments/Chambers did not consider suchcontacts to be part of political dialogue. The FinnishEduskuntasaid that political dialogue liesbetween the Finnish Republic and the Union and it considered other contacts to be "simplynormal public information and lobbying". The SwedishRiksdagconsidered that statementsfromRiksdagcommittees on Green and White Papers and non-legislative communicationsfrom the European Union are, according to its Committee on the Constitution, to beconsidered as preliminary viewpoints of a constitutionally non-binding nature.1.2.2. Presentation of the Commission Work Programme (CWP)It appears from the 40 responses that some 14 Parliaments/Chambers have never had adiscussion with a Commissioner or Commission officials on theCommission's Annual Workprogramme.10A small number of Parliaments/Chambers, some nine, received a presentationfrom a Commissioner or the EU Representation Office every year. A smaller number, some8

Commission Communication "A Citizens' Agenda - Delivering Results for Europe" COM (2006) 211 finalhttp://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2006:0211:FIN:EN:HTML9Also see the European Commission Annual Report 2005 to 2011on relations between the EuropeanCommission and National Parliaments for Commission definition of the political dialogue and other informationon this subjecthttp://ec.europa.eu/dgs/secretariat_general/relations/relations_other/npo/index_en.htm10ibid

10

six, received a presentation from a Commissioner or officials or are in the first year of startingor have recently started what may become an annual process of discussion of the CWP with aCommissioner. Five Parliaments/Chambers held two such discussions with Commissioners.One of these (the DanishFolketing)said it had since discontinued the process preferringinstead to debate the CWP between the European Affairs Committee and the Minister forForeign Affairs.1.2.3. Frequency of presentation of specific proposals in Parliaments by the CommissionAll but a small number of Parliaments/Chambers reported regularpresentations toparliamentary committees on specific proposalsby either the relevant Commissioner or thelocal EU Representation staff. The frequency of the making of such presentations varieswidely. At one end the ItalianCamera dei Deputatihad, since 2008, held 25 hearings withEuropean Commissioners, the majority of which where dedicated to the presentation anddiscussion of specific proposals of the European Commission. At the other end twoParliaments/Chambers indicated that presentations are made "infrequently" (IrishHouses ofthe Oireachtas)or "not very often" (CzechPoslanecká sněmovna).FourParliaments/Chambers (FinnishEduskunta,SlovakNárodná rada,SlovenianDržavni svet,BelgianSénatand LuxembourgChambre des Députés)indicated that they have never had apresentation or that the opportunity has not arisen.The reason for or substance of the presentations also varies widely although there is a clearinterest across many Parliaments/Chambers in receiving presentations on the Multi-annualFinancial Framework, on new economic governance rules and on the CAP reform.Presentations have been made on many matters to Committees including the following:an assessment of the Lisbon strategy;the Commission’s information strategy;EU regional and Cohesion policies;environmental protection and the related EU climate and energy package;EU enlargement strategy;the Eastern Partnership;the green paper on the European Citizens’ Initiative;the “Europe 2020” Strategy;European Commission’s country-specific recommendations of 30 May 2012;the Single Market Act;a common system of financial transaction tax;the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base;the application of the Schengenacquis;the European "Roadmap for moving to a low carbon economy in 2050";multilingualism policy and the European Union’s linguistic and educational strategy;Credit Rating Agencies III;pensions issues; anddata Protection.

11

It is encouraging to see that, subject to competing demands, Commissioners appear to bewilling to make themselves, their staff from Directorates General and their staff in EUrepresentations in capitals, available to discuss a wide range of specific subject matters.1.2.4. Strengthening the political dialogue with European institutionsDespite the evidence of the use of political dialogue the majority of national Parliaments(some 36 out of 40 responding Parliaments/Chambers) stated they believe thatpoliticaldialogue needs to be strengthenedwith all European institutions but with particularemphasis on the relationship with the Commission. The suggestions made by parliaments fordoing so are many and varied and included the following:1. increased use by national Parliaments of targeted and relevant recommendations tothe Commission to enable better responses from the Commission (the UKHouse ofLordsand DutchTweede Kamer);2. more prompt and more substantive replies from the Commission to opinions made toit (UKHouse of Lords,IrishHouses of the Oireachtas,PortugueseAssembleia daRepública,ItalianCamera dei Deputati,DutchTweede Kamer,the SpanishCortesGenerales,GermanBundesrat andDutchEerste Kamer);3. a description by the Commission of the impact of the opinions made to it in terms ofhow it influenced legislation or policy (MalteseKamra tad-Deputatiand ItalianCamera dei Deputati);4. greater consultation of national Parliaments by the Commission in advance oflegislative proposals being made particularly through the organisation of preparatorymeetings to discuss politically important proposals (FrenchAssemblée nationale,theCzechSenátand SwedishRiksdag);and5. more frequent visits by Commissioners to national Parliaments to explain proposalsincluding the use of a mandatory schedule of visits by Commissioners to nationalParliaments (PolishSenat,CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon,SlovakNárodná rada,theGreekVouli ton Ellinonand RomanianSenatul).The ItalianSenato della Repubblicaand the FrenchSénatwere the onlyParliaments/Chambers that positively commented on the political dialogue with theCommission. The ItalianSenato della Repubblicasaid that it "appears to be effective andsatisfactory, owing to the written replies to the opinions of national parliaments. Suchreplies, which are chamber-specific, have recently become more accurate, thus givingnational parliamentarians a better understanding of the Commission's positions and of thefollow-up to the legislative proposals."Effective use of visits as a tool and the need to strengthen contacts/visits with theCommission within the political dialogueIt has been seen already that there is a wide disparity as between national Parliaments interms of receivingcontacts or visitsfrom or to the Commission to discuss proposals or othermatters. The majority of national Parliaments/Chambers, some 36 of the 40 responding,nevertheless consider the visits that do occur to be an effective tool within political dialoguefor the discussion of strategic proposals or initiatives. It seems that the personal contactengendered by such visits lends itself to useful discussions on matters of strategic12

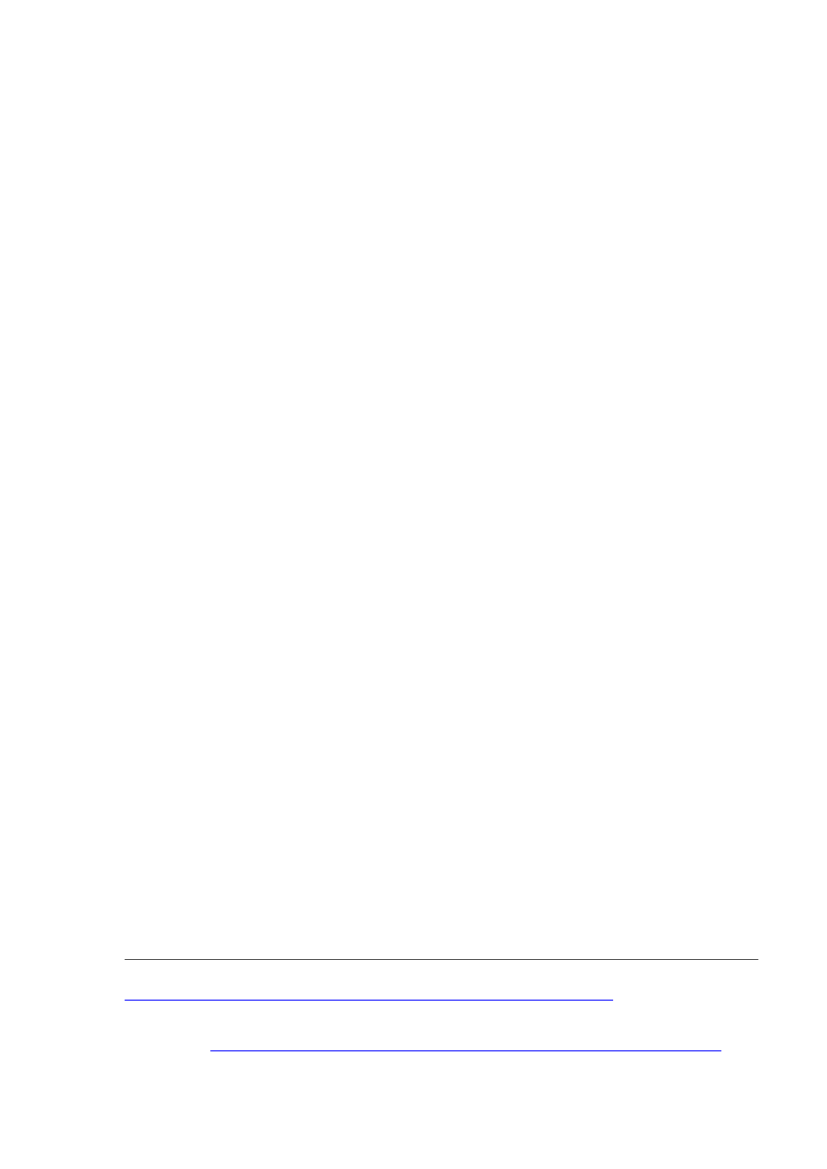

importance to national Parliaments. In view of the usefulness of such contacts, some 36 ofthe 39 responding Parliaments/Chambers believe that such contacts need to bestrengthened.The table below indicates how contacts and visits can be strengthened according to thosewho responded:Responses11%Systematic annual presentation of CWP in national Parliaments67Presentation of specific proposals by the European Commission in national 89Parliaments (upon request)Discussion with invited Commissioners in COSAC meetings81Greater use made of video conferencing with Commissioners44Total number of respondentsNo.2432291636

It is clear that a more tailored approach adapted to the needs of each national Parliament isthe most favoured option. Two Parliaments/Chambers (PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicaand DanishFolketing)believe that political dialogue could be improved if consideration weregiven to implementing the ideas set out in paragraph 6 of the Contribution of COSAC XLVII inCopenhagen of April 2012 to which the Commission has replied.12Closer cooperation between national Parliaments on proposals of particular concernThe question was raised as to whether or not Parliaments/Chambers would be in favour ofcloser cooperation between national Parliaments to discuss proposals that are of particularconcern and for which a large number of reasoned opinions (ROs) were issued,even thoughthe threshold13set out under the Lisbon Treaty for reconsideration on the part of theCommission was not met. The majority of national Parliaments/Chambers, some 34 of the 39who responded, were in favour of such an approach.When asked how such cooperation could take place the following responses were given:Responses14Letters between Chairmen of relevant committees outlining opinions toother NPsHold discussions between national Parliaments representatives in BrusselsHold discussions in the forum of COSACTotal number of respondents%687185No.23242934

11

Where "No." indicates the actual number of Parliaments/Chambers who responded and percentage (%) is theratio of the actual number of responses to the total number of respondents.12http://www.cosac.eu/denmark2012/plenary-meeting-of-the-xlvii-cosac-22-24-april-2012and Commission'sletter of response D(2012) 784008, 28 June 2012.13For the threshold see Article 7ofProtocol (No 2) Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union [OJC83/206; 30.3.2010]14Where "No." indicates the actual number of Parliaments/Chambers who responded and percentage (%) is theratio of the actual number of responses to the total number of respondents.

13

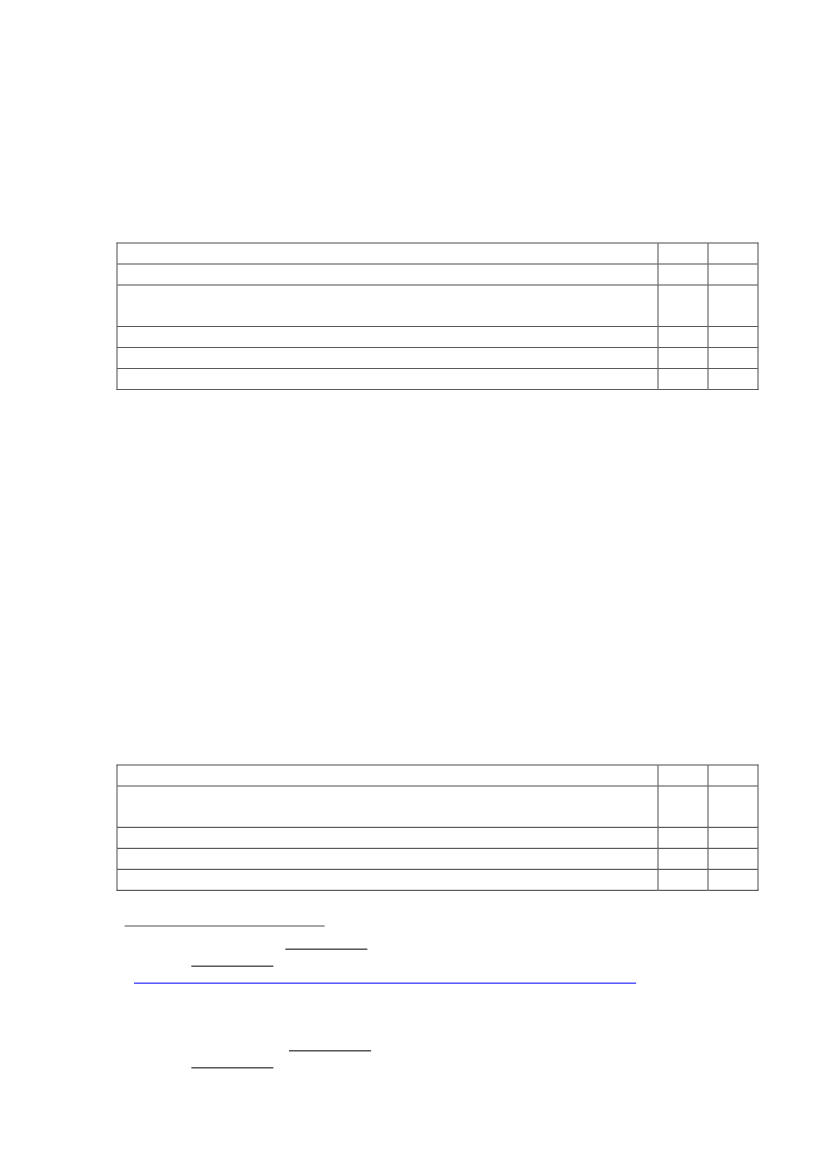

The most favoured option is the holding of discussions in the forum of COSAC. However, overhalf of those responding had other ideas which may also be interesting. These included:1. greater use of IPEX and other on-line resources (HungarianOrszággyűlés,the UKHouse of Lordsand DanishFolketing);2. the use of letters to be issued to the Commission in the joint names of severalparliaments to give added weight to their common concerns (DutchTweede Kamer);3. more working meetings of experts in the margins of COSAC such as that organised bythe Danish Presidency or other closer contacts (PolishSejm,the BulgarianNarodnosabranieand RomanianSenatul);4. exchanges of information between Members of Parliament in the margins of bothCOSAC and sectoral meetings or casual visits by MPs to other parliaments(PortugueseAssembleia da República,DanishFolketing,UKHouse of LordsandRomanianCamera Deputaţilor);5. greater use of video conferencing (UKHouse of Lordsand SwedishRiksdag);and6. more intensified use of the national Parliament Representatives as had recentlyhappened with the triggering of the yellow card on the Monti II proposal15(BelgianChambre des représentants).Two Parliaments/Chambers declared themselves to be satisfied with the currentarrangements (i.e. the SwedishRiksdagand the SlovenianDržavni svet),while the FinnishEduskuntastates that it does "not oppose any exchange of views on any topical subject, butthis can be achieved rapidly by existing means of communication. We would oppose any newformalised cooperation model."Closer cooperation between national Parliaments and the Commission on proposals ofparticular concernIn a similar vein the question was asked as to whether or not Parliaments/Chambers wouldbe in favour ofcloser cooperation with the Commission on proposals of particular concern.Some 37 of the 40 respondent Parliaments/Chambers were in favour of such closercooperation.Responses16Improved responses to ROs from the European CommissionBring to the attention of the College of CommissionersInformal dialogue with national Parliaments Representatives in BrusselsHold discussions in COSAC meetingsTotal number of respondents%81576876No.3021252837

As was seen in response to earlier questions the majority of parliaments, some 31, would liketo see improved responses from the Commission on any ROs made to it byParliaments/Chambers. This was followed by the use of COSAC for further discussion and15

COM (2012) 130; Proposal for a Council Regulation on the exercise of the right to take collective action withinthe context of the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services16Where "No." indicates the actual number of Parliaments/Chambers who responded and percentage (%) is theratio of the actual number of responses to the total number of respondents.

14

greater use of the national Parliament Representatives. Additional suggestions made alsoincluded the following: further discussions with Commissioners at the appropriate sectoralmeetings; videoconferencing between the responsible Commissioner and thoseParliaments/Chambers submitting a RO on a proposal - to include possibly the appropriateMEPs; and the possibility to adopt an ad hoc Communication where there is a large numberof ROs.The FinnishEduskuntaalso made the point strongly that "the current delays and lack ofsubstance of the Commission’s replies to ROs are unacceptable. All replies should be issuedby the Commissioner responsible for the dossier in question (in particularly important cases,by the College) and before the issue addressed by the national Parliament has been disposedof in the Council."To summarise this section, the majority of Parliaments/Chambers have undertaken someform of political dialogue, mostly written opinions. However, the majority also stated thatsuch political dialogue could be strengthened or enhanced and advanced a number of waysof improving it. In general, Parliaments/Chambers would welcome more prompt andsubstantive responses by the Commission to concerns raised by them.The majority of parliaments/Chambers have never had a discussion with a Commissioner orCommission staff on the Commission's Work programme. However, there is evidence ofsignificant and frequent contact between the Commission and/or its staff on specificCommission proposals and Parliaments/Chambers would welcome more visits andparticularly with a tailored approach by Commissioners adapted to the needs of eachParliament/Chamber.Parliaments/Chambers were, in general, in favour of closer and more frequent contacts withother Parliaments/Chambers and the Commission in respect of proposals that raise particularconcerns and for which a large number of ROs were issued. The means for such contacts arehighlighted in the Report.

15

CHAPTER 2: THE TREATY ON STABILITY, COORDINATION AND GOVERNANCE INTHE ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION AND THE ROLE OF PARLIAMENTSTheTreaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG) in the Economic andMonetary Union states in Article 13that “as foreseen in Title II of the Protocol (No 1) on therole of national Parliaments in the European Union annexed to the European Union Treaties,the European Parliament and the national Parliaments of the Contracting Parties willtogether determine the organisation and promotion of a conference of representatives ofthe relevant committees of the European Parliament and representatives of the relevantcommittees of national Parliaments in order to discuss budgetary policies and other issuescovered by this Treaty.”This chapter aims at exchanging information on the state of play on ratification of theTreaty.17It also aims at initiating a debate on how the above mentioned conference could beorganised and in which forum this may be most appropriately carried out.2.1 Ratification of the TSCGOut of 25 Member States (which is equal to 36 Parliaments/Chambers) that are signatoryparties to the TSCG, 17 national Parliaments/Chambers have responded that theratificationdocument has been deposited,18whereas 22 Parliaments/Chambers (of which 4 Chambersare not signatory parties to the TSCG) have responded that the above document has not yetbeen deposited.Concerning the expectedtimetable for depositing the ratification document,mostParliaments/Chambers estimated that the ratification process would be launched, processedor concluded during the second half of 2012, and several specifically stated that theratification process would be completed in autumn of 2012. The SwedishRiksdagstated thatthe ratification process would be dealt with during the 2012-2013 parliamentary session. TheGermanBundestagand the GermanBundesratadopted the law ratifying the Treaty on 29June 2012 and, following the ruling of the German Federal Constitutional Court, the law wassigned. The CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponindicated that the TSCG is not subject toratification by the House of Representatives and further explained that the CyprusConstitution provides that every international agreement with a foreign state or internationalorganisation relating to commercial and economic matters is concluded on the basis of adecision by the Council of Ministers.The MalteseKamra tad-Deputatistated that although the ratification document had beendeposited on 29 June 2012, a specific timetable for debate in the parliament had not yetbeen decided. The BelgianChambre des représentantsindicated “that the Federal17

This information is based on the replies from Parliaments/Chambers and is up to date at the time of writingand the situation is likely to have changed since then.18At the time of writing 12 MS already ratified: Greece, Ireland, Spain, Italy, Cyprus, Austria, Portugal, Slovenia(8 Euro MS) and Denmark, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania (4 non-Euro MS). This is the equivalent of 17 Chambers -plus Cyprus which did not ratify via an act of its Parliament.

16

Government wanted the entire procedure to be completed by the end of 2012”. The DutchTweede Kamerstated that the ratification document for the TSCG was deposited on 3 July2012 and the Committee on Finance will consider the matter following the general electionson 12 September 2012.2.2. Reinforcement of Interparliamentary co-operation on the basis of the role assigned tonational Parliaments by Article 13 of the TSCGArticle 13 provides for a forum that would involve the representatives of the EuropeanParliament and the relevant committees of national Parliaments to discuss issues arisingfrom the implementation of the TSCG. In replies to the questionnaire on this topic, someParliaments/Chambers acknowledged the need for interparliamentary co-operation andexpressed the view that Article 13 of the TSCG contributes to thereinforcement ofinterparliamentary co-operationon budgetary policies. However, nine nationalParliaments/Chambers stated that they had not yet debated the issue or taken a formaldecision. In addition, the European Parliament replied that, although it was very keen onreinforcing inter-parliamentary cooperation currently developed in the framework of theEuropean Semester, it is reflecting on this matter and had not as yet a formalised position onthe implementation of Article 13.Some took the view that interparliamentary co-operation should be reinforced on the basisof existing forums. The FinnishEduskuntacalled Article 13 “redundant” and mentionedCOSAC as the preferable forum for discussion, while the ItalianCamera dei Deputatistatedthat any decision on the implementation of Article 13 should be taken by the EuropeanUnion Speakers' Conference. The DanishFolketingsuggested that first and foremostParliaments/Chambers individually needed to engage in closer political dialogue with theEuropean Commission on issues related to the economic cooperation within the FiscalCompact and the European Semester, and added that Article 13 could be a supplement tothis cooperation in terms of exchange of best practices between national Parliaments andthe European Parliament. The SpanishCortes Generalessupported the organisation of anannual budgetary meeting, where the co-ordination of the Member States´ budgetarypolicies could be discussed.2.3 Appropriate forum for the discussion of budgetary policies and other issues asstipulated by Article 13 of the TSCGConcerning theappropriate forum for the discussionof budgetary policies and other issuesas stipulated by Article 13 of the TSCG, 10 national Parliament/Chamber did not have aformal opinion or had not yet taken a formal decision. In addition, the European Parliamenthad not yet a formalised position on the implementation of the aforementioned Article 13.Some Parliaments/Chambers (CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon,DanishFolketing,IrishHousesof the Oireachtasand SwedishRiksdag)explicitly stated that no new structures wererequired.In this context, a number of Parliaments/Chambers were somewhat flexible about the formatto be used and comments related to this included:"the appropriate forum would be the COSAC meeting, as well as the Conference ofthe Chairpersons of Finance Committee and the JCMs" (GreekVouli ton Ellinon);17

"a quick solution would have to be an interparliamentary meeting organized by therelevant committees of the European Parliament" (MalteseKamra tad-Deputati);andCOSAC or the biannual meetings of the Chairpersons of Budget Committees(HungarianOrszággyűlés).

Others preferred any future meetings to be held at committee level. Comments on thisincluded:meetings between representatives of finance committees could be used (LuxembourgChambre des Députés);"As in article 13 we will see the cooperation through organizing conferences of chairsof relevant committees" (EstonianRiigikogu);discussions could "be held at the biannual meetings of the Chairs of the finance andbudget committees" (SwedishRiksdag);and"The forum could take the form of an interparliamentary meeting involving theparticipation of the representatives of the finance/budgetary committees of thenational parliaments, as well as of the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairsof the European Parliament" (CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon).The PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicaand the IrishHouses of the Oireachtasindicatedthat a special conference should be organised and chaired by the Member State holding thePresidency of the Council, with the participation of national Parliaments and the EuropeanParliament.Yet others proposed COSAC as an appropriate forum to promote the exchange ofinformation and best practices and comments related to this included:"COSAC or a similarly structured body would be the most appropriate forum" (CzechSenát);"discussions... should preferable be conducted within the frames of COSAC by invitingmembers of relevant committees...to participate in these discussions" (DanishFolketing);"COSAC or an ad hoc meeting within the COSAC structure" (FinnishEduskunta);and"considers it appropriate for COSAC to organise an interparliamentary conference onthe specific topics as mentioned in Article 13 TSCG, without excluding othersuggestions" (DutchTweede Kamer).A number of Parliaments/Chambers stated that a conference modelled on or similar to theInterparliamentary Conference for the Common Foreign and Security Policy and the CommonSecurity and Defence Policy could be established (BelgianChambre des représentants,FrenchSénat,RomanianCamera Deputaţilorand SpanishCortes Generales).The ItalianCamera dei Deputatire-emphasised that "any decision on the implementation ofArticle 13 of the TSCG should be taken by the European Union Speakers' Conference". The UKHouse of Commonsfurther indicated that the format of interparliamentary scrutiny underArticle 13 should first be discussed and agreed in the appropriate forum, either the Speakers'Conference or COSAC. Further, the FrenchSénatand RomanianCamera Deputaţilorand theBelgianChambre des représentantssaid that the model of the inter-parliamentary18

conference for the Common Foreign and Security Policy and the Common Security andDefence Policy could be appropriate.2.4 Composition of the forum11 national Parliaments/Chambers, plus the European Parliament, had no formalised view orhad not yet discussed thecomposition of the forum.The CzechSenátand the DanishFolketingsuggested an equal number of delegates from each national Parliament and theEuropean Parliament. The CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponstated that the composition shouldbe such that would "ensure the balance in the involvement between the nationalParliaments and the European Parliament". The BelgianChambre des représentantsand theRomanianCamera Deputaţilorsuggested that the representation of national Parliamentsshould be 6 per Member State and 12 MEPsThe FrenchAssemblée nationale19proposed a conference of a flexible format, “inspired byCOSAC practices”, gathering six members of the committees on finance and other interestedcommittees of each Member and the FinnishEduskuntaproposed a conference asunregulated as possible, while the ItalianCamera dei Deputatireiterated its position that anydecision on the implementation of Article 13, including the composition of the forum, shouldbe taken by the European Union Speakers' Conference.The UKHouse of Lordssuggested that, if the forum would discuss issues wider than thoseincorporated in the Treaty, it would be desirable to have the participation of theParliaments/Chambers that are not contracting parties to the Treaty. The BulgarianNarodnoSabranieand the CzechPoslanecká sněmovnasuggested that representatives of nationalParliaments, which are not part of the Eurozone, should also participate in such aconference. The DutchTweede Kamerwas of the opinion “that also representatives of therelevant committees of national Parliaments of Member (or candidate) States of the EU thatdo not participate in the Treaty should be invited to the conference."The AustrianNationalrat and Bundesratsuggested that it is important that dialogue betweenthe Commission and national Parliaments should be ensured. Amongst otherParliaments/Chambers, the SpanishCortes Generalesand the EstonianRiigikogusuggestedthe chairs of the relevant committees, both in national Parliaments and in the EuropeanParliament should participate.To summarise this chapter, most Parliaments/Chambers reported that the ratificationdocument for the TSCG has not yet been deposited, but, indicated that, during the secondhalf of the year 2012, the ratification procedure would proceed. Concerning thereinforcement of interparliamentary co-operation as stipulated by Article 13 of the TSCG,Parliaments/Chambers emphasised that Article 13 provides a platform for closer co-operation. With regards to the appropriate forum and its composition, it seems that therehave been, as exemplified in the Report, varying views and that more discussion should beexpected on this matter in the future.19

See Report: "Le Gouvernement économique européen face à la crise: le rendez-vous franco-allemand pourporter une ambition pour l´Europe" by Pierre Lequiller.http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/13/europe/rap-info/i4449.asp

19

CHAPTER 3: ENERGY - TRANS EUROPEAN ENERGY INFRASTRUCTURETheCommission proposal on guidelines for trans-European Energy infrastructureadoptedon 19 October 2011,20aims at laying down rules for the development and interoperability oftrans-European energy networks, in order to ensure the functioning of the internal energymarket, the security of energy supply in the Union, the promotion of energy efficiency, thedevelopment of new and renewable forms of energy, and the promotion of theinterconnection of energy networks.The above proposal constitutes part of the Union’s efforts to modernise and expandEuropean energy infrastructure as set out in the Commission Communication on energyinfrastructure priorities for 2020 and beyond, adopted on the 17thNovember 2010.21Thiscalled for a new infrastructure policy to coordinate and optimise network development inEurope. The Commission Communication “A budget for Europe 2020”, adopted on the 29thJune 2011,22proposed the creation of the Connecting Europe Facility through which thecompletion of priority energy, transport and digital infrastructures will be promoted, settingaside a budget of €9.12bn for investment in the field of energy.Chapter 3 of the Bi-annual Report aims at exchanging information pertaining to the aboveproposal between Parliaments/Chambers in order to facilitate the substantive debate of theproposal as well as its future implementation.3.1 Parliamentary scrutiny of the proposalParliaments/Chambers were asked whether theyscrutinised the proposal,for which reasonsthey agree or disagree with the objectives set out therein and whether they submitted anopinion in the framework of the political dialogue or adopted any other parliamentarydocument (e.g. resolution, report, decision, reasoned opinion etc.).27 of 41 Parliaments/Chambers scrutinised the proposal for a Regulation of the EuropeanParliament and of the Council on guidelines for trans-European Energy infrastructure andrepealing Decision No 1364/2006/EC (COM(2011) 658) while 14 Parliaments/Chambersreplied that they did not.Four Parliaments/Chambers submitted a contribution on the proposal, while 11 adoptedanother parliamentary document such as resolutions or reports in committees. No ReasonedOpinions were adopted.

20

Commission proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on guidelines for trans-European Energy infrastructure and repealing Decision No 1364/2006/EC (COM(2011) 658). -http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0658:FIN:EN:PDF21Communication from the Commission on Energy infrastructure priorities for 2020 and beyond - a Blueprintfor an integrated European energy network (COM(2010) 677) -http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SPLIT_COM:2010:0677(01):FIN:EN:PDF22Communication from the Commission on A budget for Europe 2020 (COM(2011) 500/I &II final) -http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2011:0500:FIN:EN:PDF

20

Of those who scrutinised the proposal, 25 Parliaments/Chambers replied to the question ifthey agreed with the objectives, with 17 being in favour and eight being partly in favour ofthe objectives and none against.23Most of those 17 Parliaments/Chambers that agreed with the proposal and its objectives,stated their conviction that the proposal would contribute to reaching the core objectives ofEU energy policy, namely the completion of the internal market for energy, competitiveness,the diversification and security of supply. Two Parliaments/Chambers (the ItalianSenatodella Repubblicaand the European Parliament) linked these objectives to achieving the 2020energy objectives. The GermanBundesratemphasised that coordinated expansion of energyinfrastructure at the EU level is an essential prerequisite to attain the energy policy goal ofsafe, affordable and climate-friendly energy supply both at the European level and at thelevel of the Member States. The MalteseKamra tad-Deputatiand the DutchTweede Kamerregarded the proposal as a priority and the FinnishEduskuntaas well as both RomanianChambers pointed out that it was congruent with the national priorities for energy. While theEstonianRiigikoguexpressed its overall support for the EU energy action plan, the DutchTweede Kamer,the SwedishRiksdagand the PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicapointedout the need for European cooperation in this field.Despite their general support for the proposal eight Parliaments/Chambers criticised severalof its specific aspects. Addressing a general issue, the two UK Chambers considered thebudget proposed as over-ambitious, while the CzechSenátpointed out that the funds for theConnecting Europe Facility should not be transferred from the Cohesion Fund. The SlovenianDržavni svetand the UKHouse of Commonsshared concerns about the principle for theallocation of EU support which should be limited to projects with a clear EU-added valuewhile upholding the "consumers pay" principle for commercially attractive investments. Incontrast to that the UKHouse of Lordswould like to see economic viability to be put at thecentre of considerations. The SlovenianDržavni svetand the CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponwere concerned about the provisions regarding the distribution of investment costs which,according to them, could present a risk to small countries (SlovenianDržavni svet)and shouldensure that the return of each project is consistent with the risk undertaken (CyprusVouliton Antiprosopon).The following were among the particular concerns mentioned by individualParliaments/Chambers:the level of control the Commission would take over the direction of the projects andthe key role that had to be secured for Member States (UKHouse of Lords);the insufficient definitions of certain concepts and the unclear working patterns ofregional groups (SlovenianDržavni svet);the regulatory treatment and the eligibility of projects of common interest (PCIs)(CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon);the fact that more cross-border interconnectors should not excuse Member Statesfrom producing the electricity they consume (FrenchSénat);and

23

Two Parliaments/Chambers did not provide further information on their positive scrutiny result. See annex onCOSAC website for full information on replies giving the response of each Parliament/Chamber.

21

the potential encroachment on Member States’ planning law and the necessaryrespect of the constitutionally guaranteed competence of the federal states (Länder)for implementation and design of planning and permit granting procedures (GermanBundesrat).

3.2 Specific questions considered in scrutinyParliaments/Chambers were asked to state whether they considered specific questionsarising in connection with the proposal and had an opportunity to provide additionalinformation related to the proposal.Environmental protection(i) It is interesting to point out that ten Parliaments/Chambers considered whether theproposed legislation affords adequate protection to the environment whilst promoting thedevelopment of trans-European energy networks, but none of them voiced any criticism inthis regard. For example, the CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponnoted the inclusion of provisionsregarding the protection of the environment and the Commission's pledge that measurespromoted under this proposal will not undermine EU environmental legislation. Only thegovernment statement in the UKHouse of Commonspointed to the need for additionalinformation on how the money will be spent best to aid growth and to supportenvironmental objectives. However, the DanishFolketingargued for a higher priority ofgreen elements which might contribute to achieving the 2020 goals and the 2050 objectivesthroughout the proposal and the European Parliament examines strengtheningenvironmental provisions in amendments.Transparency and effective participation(ii) Eight Parliaments/Chambers replied that they had scrutinised whether the proposedRegulation adequately addresses transparency and effective participation of the publicduring consultations for a proposed infrastructure project, in the light of the time constraintsimposed by the "fast track" permit granting procedure. While the CyprusVouli tonAntiprosoponand the FrenchSénatexpressed concerns as to whether effective consultationsof the public can be achieved within the short time frames set by the proposal, the GermanBundesratwelcomed the much earlier consultation and broader basis of involvement of thegeneral public (not just direct stakeholders). The European Parliament looked intosuggestions how to carry out the public consultations in order to ensure maximumtransparency despite the time constraints.Permit granting process(iii) 11 Parliaments/Chambers confirmed that they considered whether a reorganisation ofthe permit granting process in their country would be needed in order to enable decisionswithin the time constraints imposed by the Regulation, especially in cases where multipleauthorities are engaged. Several Member States will have to adjust their permit grantingprocesses according to the replies from the PolishSejm,the UKHouse of Lords,the CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponand the FrenchSénat.The GermanBundesratdrew attention to thefact that Germany has entirely revised and considerably accelerated the planning and permitgranting procedure for electricity transmission grids thanks to the Grid ExpansionAcceleration Act (Netzausbaubeschleunigungsgesetz/NABEG) of which the innovations werecalled into question again by the Commission proposal. The LatvianSaeimavoiced concerns22

about the feasibility of ensuring a timely establishment of a new institution for issuingpermits for projects of common interest. The SwedishRiksdag(as does the GermanBundesrat)underlined the need to respect national sovereignty with regard to the permitgranting procedures and the FinnishEduskuntareminded that the permit granting processhas to take into consideration other legitimate interests such as the adequacy and sufficientexpertise of environmental impact assessment processes, constitutionally protected rights ofmunicipalities and adequate possibilities for public participation and access to information.Projects of common interest (PCIs)(iv) Ten Parliaments/Chambers replied that they had looked into the question of whetherthey had any objections with regard to the rules set out by the proposed regulationconcerning the eligibility of projects of common interest (PCIs) for financial assistance fromthe EU. Only the CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponmentioned this point as an initial stumblingblock for its support of the Commission proposal but concedes that in the meantime many ofits comments and suggestions concerning the criteria for the selection of projects of commoninterest (PCIs) had been taken into consideration. Contrary to that, the FrenchSénatstatedthat it did not have any objection to the defined rules from the outset. At the same time, theEuropean Parliament examined whether the rules need to be better defined, in particular asregards the governance of regional groups (as was requested also by the RomanianCameraDeputaților).3.3 Content of contributions and parliamentary documentsThose 15 Parliaments/Chambers which submitted contributions or adopted any otherdocument were asked to summarise the content of their documents. Only threeParliaments/Chambers, the BulgarianNarodno sabranie,the ItalianSenato della Repubblicaand the SlovenianDržavni svet,made additions to what had already been presented above.The BulgarianNarodno sabraniesupported the Connecting Europe Facility, the optimisedpermit granting procedures (as mentioned as well by the SlovenianDržavni svet),thedesignation of trans-European priority corridors (as the ItalianSenato della Repubblicaandthe SlovenianDržavni svet),the designation of projects of common interest (as the ItalianSenato della Repubblicaand the SlovenianDržavni svet).The ItalianSenato della Repubblicaalso spoke out in favour of Smart Grids, a role for sponsors of private industrial projects inthe designation of the European Coordinator, a model of choice between simplifiedauthorisation procedures, avoiding the risk that the new cost-benefit analysis methodologyresults in cost for the users and a safeguard clause in favour of commercially viable projects.The Council Presidency and the European Parliament's rapporteur are committed to worktowards the adoption of the proposal by the co-legislators by the end of 2012/beginning of2013. Depending on the trialogue negotiations the European Parliament plenary couldpossibly adopt a position in January 2013.To summarise this chapter, the replies to the questions show that two thirds ofParliaments/Chambers scrutinised the above mentioned proposal while one third chose notto do so. Of those Parliaments/Chambers that scrutinised the above mentioned proposal twothirds were in favour and one third partly in favour of its objectives; none were

23

against. However, several national Parliaments expressed selective concerns over variousspecific aspects of the above proposal which are documented in this Report.It can be deducted from Parliaments'/Chambers' replies that future inter-parliamentarydiscussions on the substance of the proposal could revolve around questions linked to thefunding, the allocation of EU support, the distribution of investment costs, the level ofcontrol by the Commission over the direction of projects and the role for Member States, theworking patterns of regional groups the regulatory treatment and the eligibility of projects ofcommon interest and the design of permit planning procedures as well as the pros and consof the much earlier consultation and broader basis for involvement of the general public.

24

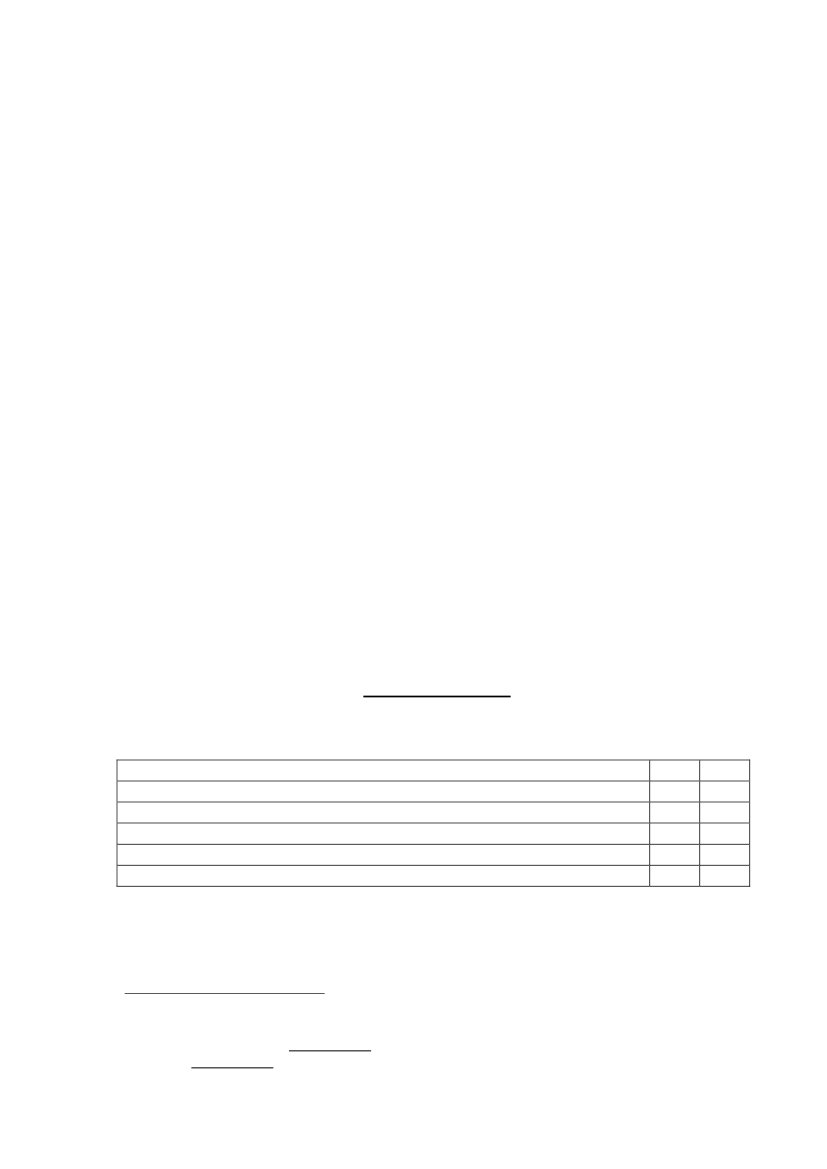

CHAPTER 4: SINGLE MARKET GOVERNANCEIn relation to the re-launch of the Single Market, the Europe 2020 Strategy and thecontinuing financial crisis, the Commission presented in June 2012 a Communication onbetter governance for the Single Market.24As can be seen in the latest governance check-upof the implementation of Single Market directives the average transposition deficit has risenfrom 0.7% in 2009 to 1.2% in February 2012.25The Commission Communication states that amore efficient transposition of EU legislation could lead to an overall cost saving of almost 40billion euro and calls for a renewed commitment to make the Single Market deliver. In the17th Bi-annual Report several Parliaments/Chambers underlined the "need to improveMember States' transposition and application of EU legislation" and a discussion on SingleMarket governance was opened at the XLVII COSAC meeting in Copenhagen April 2012. Thisdiscussion will be continued with an organised debate on Single Market Governance at theXLVIII COSAC meeting in Nicosia in October 2012.The fourth chapter of the 18th Bi-annual Report aims to facilitate the exchange ofinformation about the parliamentary activity around the subject of better governance for theSingle Market.4.1 Parliamentary scrutiny of Single Market governanceOut of 40 respondents, 12 Parliaments/Chambers replied that they had considered theCommission Communication"Better governance for the Single Market"or the role ofnational Parliaments in the transposition of Single Market legislation (e.g. the DanishFolketing,the RomanianSenatuland the UKHouse of Lords).However, an additional eightParliaments/Chambers expressed their intention to hold a debate on the subject or havealready scheduled a discussion in the near future (e.g. the GermanBundestag,the HungarianOrszággyűlésand the PolishSejm).26The DutchTweede Kamerstated that the governance ofinternal market directives has been debated, but that the "role of national parliaments intransposition and effective implementation of European legislation on the internal marketdid not receive particular attention".Of those Parliaments/Chambers which have already considered the subject, five answeredthat they have submitted an opinion or a parliamentary initiative. The BulgarianNarodnosabranieadopted in May 2012 a statement in which the Committee on European Affairs andOversight of European Funds called for effort at EU-level focusing on "better use of the singleMarket's untapped potential by removing the remaining obstacles, complying with its rulesand turning it into an engine of growth". It expressed furthermore concern with the existingrestrictions on free movement of people within the EU and the "lack of full mutual24

COM (2012) 259, "Better governance for the Single Market" -http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2012:0259:FIN:EN:PDF25"Making the Single Market deliver, Annual Governance Check-up 2011", European Commission, InternalMarket and Services, 27.02.2012 -http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/score/index_en.htmor thebackground note produced for the XLVII COSAC Meeting by the COSAC Secretariat, "State of transposition andenforcement of Single Market directives in the EU Member States" -http://www.cosac.eu/denmark2012/plenary-meeting-of-the-xlvii-cosac-22-24-april-2012/26See annex on COSAC website for full information on replies giving the response of each Parliament/Chamber.

25