Europaudvalget 2012-13

EUU Alm.del Bilag 498

Offentligt

17 May 2013

Nineteenth Bi-annual Report:Developments in European UnionProcedures and PracticesRelevant to Parliamentary Scrutiny

Prepared by the COSAC Secretariat and presented to:XLIX Conference of Parliamentary Committeesfor Union Affairs of Parliamentsof the European Union23-25 June 2013Dublin

Conference of Parliamentary Committees for Union Affairsof Parliaments of the European UnionCOSAC SECRETARIATWIE 05 U 041, 50 rue Wiertz, B-1047 Brussels, BelgiumE-mail: [email protected] | Tel: +32 2 284 3776

ii

Background .....................................................................................................................................ivABSTRACT........................................................................................................................................ 1CHAPTER 1: GENUINE ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION ......................................................... 41.1 Parliamentary activities and views on key EMU documents................................................ 41.2 Views on certain aspects of a deepening of the EMU ...................................................... 51.3 The role of Parliaments in terms of democratic legitimacy and accountability............... 61.4 Consideration of democratic legitimacy and accountability and the role of nationalParliaments and the European Parliament in key EMU documents ...................................... 71.5 December 2012 European Council Conclusions - democratic legitimacy andaccountability.......................................................................................................................... 81.6 Parliamentary preparation for European Council meetings and scrutiny of EuropeanCouncil conclusions............................................................................................................... 11CHAPTER 2: EUROPEAN SEMESTER 2013 ..................................................................................... 132.1. Engagement in the economic governance of the EU and the European Semester atnational level in 2013............................................................................................................ 132.2. Scrutiny of Annual Growth Survey 2013........................................................................ 142.3. Scrutiny of Documents in 2013...................................................................................... 142.4 Role of Committees in preparation of key documents................................................... 152.5. Engagement of national Parliaments/Chambers with the European Commission in theEuropean Semester process ................................................................................................. 162.6. Increased participation of Parliaments/Chambers in the European Semester since theprocess began in 2011 .......................................................................................................... 162.7. European Parliamentary Week...................................................................................... 172.8 Optimum forum for interparliamentary cooperation at European level on the EuropeanSemester ............................................................................................................................... 182.9 Changes to procedures at national level in response to the European Semester ......... 19CHAPTER 3: EUROPEAN UNION ENLARGEMENT .......................................................................... 213.1 Practices and procedures within Parliaments in relation to the enlargement process . 213.2 Monitoring reports, annual progress reports and the enlargement strategy................ 223.3 Dialogue with political, official and civil society representatives in enlargement states............................................................................................................................................... 233.4 Enhancing the national discourse on enlargement in the EU Member States .............. 24CHAPTER 4: SUBSIDIARITY ............................................................................................................ 264.1 Updated subsidiarity scrutiny procedures in Parliaments/Chambers and examples ofinnovation and best practise ................................................................................................ 264.2 Appropriate time period for internal parliamentary scrutiny of subsidiarity ................ 284.3 Methods and/or networks used by Parliaments/Chambers to exchange information onsubsidiarity and their influence over particular scrutiny outcomes..................................... 284.4 Improvements to increase the effectiveness of the interparliamentary exchange ofinformation on the scrutiny of subsidiarity .......................................................................... 294.5 Improvement of European Commission responses to reasoned opinions .................... 30"Monti II"............................................................................................................................... 304.6 Exchange of information on the "Monti II" proposal ..................................................... 314.7 The European Commission response to "Monti II" ........................................................ 32

Table of Contents

1iii

BackgroundThis is the Nineteenth Bi-annual Report from the COSAC Secretariat.COSAC Bi-annual ReportsThe XXX COSAC decided that the COSAC Secretariat should producefactual Bi-annual Reports, to be published ahead of each ordinary meetingof the Conference. The purpose of the Reports is to give an overview ofthe developments in procedures and practices in the European Union thatare relevant to parliamentary scrutiny and to provide information betterto facilitate plenary debates.All the Bi-annual Reports are available on the COSAC website at:http://www.cosac.eu/en/documents/biannual/The four chapters of this Bi-annual Report are based on information provided by the nationalParliaments of the European Union Member States and the European Parliament. The deadlinefor submitting replies to the questionnaire for the 19th Bi-annual Report was 28 March 2013.The outline of this Report was adopted by the meeting of the Chairpersons of COSAC, held on28 January 2013 in Dublin.As a general rule, the Report does not specify all Parliaments or Chambers whose case isrelevant for each point. Instead, illustrative examples are used.Complete replies, received from 39 out of 40 national Parliaments/Chambers of 26 out of 27Member States and the European Parliament, can be found in the Annex on the COSACwebsite.Note on NumbersOf the 27 Member States of the European Union, 14 have a unicameralParliament and 13 have a bicameral Parliament. Due to this combination ofunicameral and bicameral systems, there are 40 national parliamentaryChambers in the 27 Member States of the European Union.Although they have bicameral systems, the national Parliaments of Austria,Ireland and Spain each submitted a single set of replies to the questionnaire,therefore a the maximum number of respondents per question is 38. There were37 responses to this questionnaire.

iv

ABSTRACTCHAPTER 1: GENUINE ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNIONThe majority of Parliaments/Chambers actively debate key EMU related documents and havefound them to be a useful basis for discussion, mostly in committee but occasionally inplenary. There was some concern that policy measures previously announced or alreadyagreed should be advanced or implemented as quickly as possible.In terms of democratic legitimacy Parliaments/Chambers should aim at making greater use ofexisting tools and seek to develop new ones such as the right of initiative. There is a beliefthat the key documents relating to the EMU referred to in this report do not adequatelyaddress the issue of democratic legitimacy for Parliaments as they are not clear enough onwhat is being proposed and there is a concern that democratic legitimacy should bedeepened.Most Parliaments/Chambers see the need for appropriate parliamentary structures andinstruments aimed at strengthening the role and involvement of Parliaments in EU levelconsideration of new economic measures which affect citizens as a way of increasingdemocratic legitimacy. While the arrangements for the new Article 13 Conference will beimportant in showing how Parliaments can work together effectively in this regard somenational parliaments equally do not necessarily want an overly EU centralised system for thedevelopment of economic policy. There were nonetheless high levels of support for theconcepts that accountability should rest at the level at which decisions are taken andimplemented and equally for further integration to be accompanied by the commensurateinvolvement of the European Parliament.Although the response level was low on the specific questions asked, it is safe to say thatthere were no negative reactions among Parliaments/Chambers to the concept of theestablishment of, for example, a single resolution mechanism or the ex-ante coordination ofmajor economic reforms. It may, however, have been too early to seek views on thesematters.Parliaments/Chambers, in general, have a wide range of useful and well used mechanisms tohelp them prepare national policy positions before and after European Councils includingdebates with prime Ministers and with other Ministers at Plenary and committee levels.CHAPTER 2: EUROPEAN SEMESTER 2013The majority of Parliaments/Chambers reported that they were satisfied or partly satisfiedwith their degree of engagement in the economic governance of the EU and the EuropeanSemester at national level in 2013. Likewise, the majority of Parliaments/Chambers answeredthat they had scrutinised the Annual Growth Survey 2013. The majority ofParliaments/Chambers also scrutinise or plan to scrutinise the draft Stability andConvergence Programme (SCP), National Reform Programme (NRP) and the Country-SpecificRecommendations (CSR) at committee level. Just under half the respondents have changedor plan to change procedures in their Parliament/Chamber in order to respond to the1

European Semester and the Report highlights a number of examples of best practice in thisarea.Seventeen Parliaments/Chambers responded that they had engaged with the EuropeanCommission in some part of the process and some noted the publishing of specific reports orthe arrangement of special briefings for Members or the appointment of a rapporteur tocoordinate political positions as useful techniques for increasing engagement.With regards to whether Parliaments/Chambers plan to scrutinise the Draft Stability andConvergence Programme, the National Reform Programme and Country-SpecificRecommendations, most Parliaments/Chambers reported that they will, either ex-anteand/or ex-post. Concerning the participation of Parliaments/Chambers in the EuropeanSemester since the process began in 2011, the majority answered that this has increased.Likewise, a great majority of Parliaments/Chambers reported that they had participated inthe European Parliamentary Week (EPW), while around a third of them responded that theEPW had enhanced their involvement in the European Semester. The organisation of theEPW, however, requires reviewing according to some Parliaments/Chambers as it did notfacilitate proper discussion among parliamentarians particularly with the early departure ofkeynote speakers.Support for the optimum forum for interparliamentary cooperation at European level on theEuropean Semester varied and was divided between the EPW, the idea of aninterparliamentary conference and the use of existing fora or a combination of existing fora.CHAPTER 3: EUROPEAN UNION ENLARGEMENTFor the ratification of an accession treaty in most cases an Act of Parliament is needed and intwo cases a referendum might have to be held.Monitoring reports (on acceding countries) and annual progress reports (on candidate andpotential candidate countries) were scrutinised and debated by around 60% of respondingParliaments/Chambers. Half of the respondents discussed the Commission's EnlargementStrategy 2012-2013. Most Parliaments/Chambers debate enlargement in relation to allcandidate and potential candidate countries while just five Parliaments/Chambers did notdiscuss on any of them at all.While two thirds of the respondents answered that their Parliament/Chamber engages indialogue with political, official and civil society representatives in enlargement states, theintensity of this involvement as well as the interlocutors vary widely.The understanding of Parliaments'/Chambers' own role in enhancing the public discourse intheir Member State is very complex. Some do not see a role for themselves in this regard atall, others describe this as a matter to be dealt with principally by their governments, while afew see a need for public communication and for a well-informed public debate.

2

CHAPTER 4: SUBSIDIARITYAlthough formal procedures of subsidiarity scrutiny have remained unchanged in recentyears, some Parliaments/Chambers adopted important changes in the practical application ofthe procedures. Best practices related to putting more focus on improving co-operation withother Parliaments/Chambers and included: the exchange of information between membersof staff of different Parliaments; cooperation among National Parliament Representatives ofParliaments/Chambers to the EU; and attendance of interparliamentary conferences anddebates with other MPs.Around two thirds of Parliaments/Chambers answered that the eight-week period wassufficient for scrutiny of subsidiarity under the Lisbon Treaty. However, a longer periodwould make the process easier and mitigate the impact of periods of holidays andparliamentary recess. Twelve Parliaments/Chambers believed that the eight-week period wasnot sufficient and emphasised that an extension would not mean a significant slowing downof the European legislative procedure.There has been significant exchange of information between Parliaments/Chambers onsubsidiarity scrutiny using a variety of exchange methods and networks, in particular email,the IPEX database and National Parliament Representatives based in Brussels. This shows thesuccessful intensification of interparliamentary exchange of information since the cominginto force of the Lisbon Treaty, in many cases contributing to specific scrutiny outcomes.These overall trends are also reflected in the specific case of "Monti II".Half of responding Parliaments/Chambers called for European Commission’s replies toreasoned opinions to be provided in a swifter manner and a further 20 out of 33 for them tobe more focused on the arguments contained in the opinions drafted by the nationalParliaments to ensure continuing genuine dialogue between the Commission and nationalParliaments. In the specific case of "Monti II" the majority of Parliaments/Chambers believedthat the European Commission actions in responding to the "yellow card" were in line withthe Lisbon Treaty and that it applied correctly the practical arrangements for the operation ofthe subsidiarity mechanism. However, 12 Parliaments/Chambers did not believe that thereply from the Commission to the reasoned opinion (dated 12 September 2012) was anadequate response.

3

CHAPTER 1: GENUINE ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNIONIn November 2012, the European Commission published a Communication of majorsignificance setting out a blueprint for a deep and genuine economic and monetary union(EMU),1with a view to launching a debate. In this document the Commission highlighted themeasures already taken during the current crisis and set out possible measures to deepenEMU in the short, medium and long term, including possible steps towards a political union.In December 2012, the European Council adopted conclusions2on a roadmap for thecompletion of EMU. The conclusions dealt with the most immediate aspects of the roadmapdrawing on a report on the issue published earlier that month by President of the EuropeanCouncil Mr Herman Van Rompuy.3The report identified four main building blocks for thecompletion of EMU: an integrated financial framework; an integrated budgetary framework;an integrated economic policy framework; and democratic legitimacy and accountability.This section of the Report will summarise information provided by Parliaments/Chambers onthe level of debate within Parliaments/Chambers on the European Commission’s blueprintfor a genuine EMU, given its intended purpose as a debate-starter, and will summarise theviews of Parliaments on some of the possible measures outlined therein, and in the VanRompuy report, such as the promotion of structural reforms in Member States througharrangements of a contractual nature, and the creation of a euro area fiscal capacity.Finally, this section of the Report will summarise the views of Parliaments/Chambers on theextent to which these three key EMU documents have sufficiently addressed the issue ofdemocratic legitimacy and accountability, and in particular the role of Parliaments, in agenuine EMU.1.1 Parliamentary activities and views on key EMU documentsThe results show that more than three quarters of responding Parliaments/Chambers havescrutinised the key documents described above. This has taken place either in plenary orcommittee sessions, and in the case of the European Council conclusions either beforeand/or after the Council according to the tradition of the respective Parliaments/Chambers.In one case the HungarianOrszággyűlésmentioned that the debate with their Prime Ministeron the European Council conclusions was done "in camera". In another case, the DutchTweede Kamerheld a public roundtable on the future of EMU during which "about 20authorities and experts were invited to share their insights".Nine respondents did not scrutinise the Commission Blueprint, while eight did not scrutinisethe Van Rompuy Report and seven did not scrutinise the European Council conclusions.When asked to comment further some Parliaments/Chambers noted that the documentswere a sound basis for the discussion on the future direction of the EMU or created greater12

COM (2012) 777http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2012:0777:FIN:EN:PDF14 December 2012http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/134353.pdf3Towards a Genuine Economic and Monetary Union, 5 December 2012http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_Data/docs/pressdata/en/ec/134069.pdf

4

understanding around the process of developing and deepening the EMU and are stillcontinuing to do so (the ItalianSenato della Repubblica,the LithuanianSeimas,theHungarianOrszággyűlésand the DutchTweede Kamer).For others the documents werebackground material which fed into their regular policy debates on these matters.Of the 34 respondents, 29 said that the documents contributed to a debate in theirParliament/Chamber on the future direction of the EMU in committee and 10 of these alsosaid it contributed to a debate in plenary session. A small number (five) had not debated thedocuments.Of the 14 Parliaments/Chambers which responded to the question about their overallreaction to the documents, there was a clear and positive reaction to all three documents. Allbut one of these respondents (CzechPoslanecká sněmovna)considered the steps set out inthe documents to be necessary and all but two considered them realistic (CzechPoslaneckásněmovnaand UKHouse of Lords).However, given the low response rate this is merely a verybroad indication of sentiment towards these documents.In the follow-on comments the views of Parliaments/Chambers became more nuanced. It isclear that the documents cover a wide variety of issues and that some Parliaments/Chambersdid not have one overall view on them. A number were still reflecting on the documents andhad not reported on them and some referred to previous reports expressing support for thedeepening of the EMU more generally. However, many welcomed the documents as a stepforward in the right direction. In that regard this broad support was tempered by somecritical comments: the European Parliament pointed out the absence of any mention of "themutualisation of debt or of the redemption fund" or of a "European Treasury" or of furtherexplanation of "the fiscal capacity"; some called for the measures that had already beenagreed to be implemented effectively as soon as possible [6 pack, 2 pack, etc.] and evaluated(the FrenchAssemblée nationale,the EstonianRiigikoguand the SwedishRiksdag);the UKHouse of Commonsexpressed deep concern about the possible implications for the UK ofwhat was being proposed; "the need for immediate clarification of the operationalframework for the recapitalisation of banks through the ESM, in a direct and retrospectiveway, for countries in an adjustment programme" was called for by the GreekVouli tonEllinon;the notion of a contractual relationship between the Union and each state wascriticised by the FrenchSénat;and the AustrianNationalratandBundesratpointed out theabsence of any mention of or a commitment to a convention for the revision of the Treaties.1.2 Views on certain aspects of a deepening of the EMUParliaments/Chambers were asked to give information about their views on a number ofproposals for deepening the EMU currently being considered at EU level. This was an attemptto get a first reaction. The results are best shown in tabular form as set out below.

5

Question

Positive

Negative

Necessarysteps

Unnecessarysteps

Realistic

Unrealistic

SRM4Ex-antecoordinationof majoreconomicreforms inthe shorttermEx-antecreation of aCCI in theshort term5Possiblecreation of afiscalcapacity fundfor the euroarea in themediumtermPossiblecreation of aredemptionfund for theeuro area inthe mediumterm

1511

10

96

00

96

01

8

1

5

1

4

2

9

3

6

1

6

1

8

3

5

1

6

1

Many Parliaments/Chambers have yet to take a formal position on these matters. Some havesaid they are awaiting Commission proposals before doing so and some have said they will beexamining these matters in the next semester. The SpanishCortes Generalesnoted that ithad asked its government to link the fiscal capacity fund to the question of economic growthand jobs while the DutchTweede Kamerdid not agree with the creation of the fund.1.3 The role of Parliaments in terms of democratic legitimacy and accountabilityIn response to the question on their role in terms of democratic legitimacy andaccountability, a number of Parliaments/Chambers referred to fact that their role is toactively scrutinise their own governments. However, it is also clear that many look to thebroader European stage. The DanishFolketingdefined itself "as an active player scrutinisingthe national government as well as European decision-making; applying existing tools to4

A single resolution mechanism [SRM] for the recovery and resolution of banks within the Member States participating inthe Banking Union in the short term5Convergence and Competitiveness Instrument (CCI)

6

European decision-making and to developing new tools - for instance throughinterparliamentary cooperation". The GermanBundestagreferred to the need to "getinformed extensively" and "to be involved in a coordinating role at an early stage". TheLatvianSaeimabelieved that existing instruments for economic policy coordination have tobe used to the utmost extent and agreed that there should be ex-ante economic policycoordination. The SpanishCortes Generalesnoted that the role of Parliaments in the EUshould be increased, while the LithuanianSeimascited the need for systematic involvementof national Parliaments both aimed at ensuring the necessary democratic legitimacy andaccountability of decision making in the EMU. The AustrianNationalratandBundesratargued that it had to make use of new instruments and mechanisms and to become moreinvolved while it also said that Parliaments/Chambers needed to create new mechanisms, onthe European level and between national Parliaments and the EU institutions, which have fulldemocratic accountability. The European Parliament mentioned the recommendationscontained in its "Thyssen report"6and notably that "the future architecture of the EMU mustrecognise that the European Parliament is the seat of accountability at Union level". Inaddition it pointed out that "the Commission and the Council should be present when inter-parliamentary meetings between representatives of national Parliaments andrepresentatives of the European Parliament are organised at key moments of the Semester(i.e. after the release of the Annual Growth Survey, and after the release of the Country-Specific Recommendations), notably allowing national Parliaments to take into account theEuropean perspective when discussing the national budgets". The IrishHouses of theOireachtasstated that "initial steps towards the completion of the EMU have taken placewithout any significant change to the role of Parliaments in the institutional mix at EU level".The SwedishRiksdagnoted, however, that the suggested measures represent "a significantcentralisation of economic policy in the EU" which is a "worrying development". It also saidthat national parliamentary control on budgetary matters should not be weakened and theSlovenianDržavni zboragreed on this point too.The DutchTweede Kameracknowledged "the feelings of citizens who do not feelrepresented in the on-going developments in Europe" and wanted clear arrangements on astrengthened democratic legitimacy and accountability and instruments in the field of theBanking Union, the Fiscal Union and the Economic Union in which national Parliaments playan effective and adequate role".1.4 Consideration of democratic legitimacy and accountability and the role of nationalParliaments and the European Parliament in key EMU documentsThere is a clear belief among those Parliaments/Chambers which responded that the keydocuments do not adequately consider the issues of democratic legitimacy andaccountability and, in particular, the role of the national Parliaments and the EuropeanParliament. Fifteen out of 21 (71.4%) of those who responded believe this to be the casewith the Van Rompuy Report and the European Council conclusions of December 2012. TheCommission Blueprint, at 13 out of 19 (68.4%), fared only marginally better. In furthercomments Parliaments/Chambers outlined the reasons for this. Some Parliaments/Chambers6

European Parliament resolution of 20 November 2012 with recommendations to the Commission on the report of thePresidents of the European Council, the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the Eurogroup ‘Towards agenuine Economic and Monetary Union’ (2012/2151(INI)

7

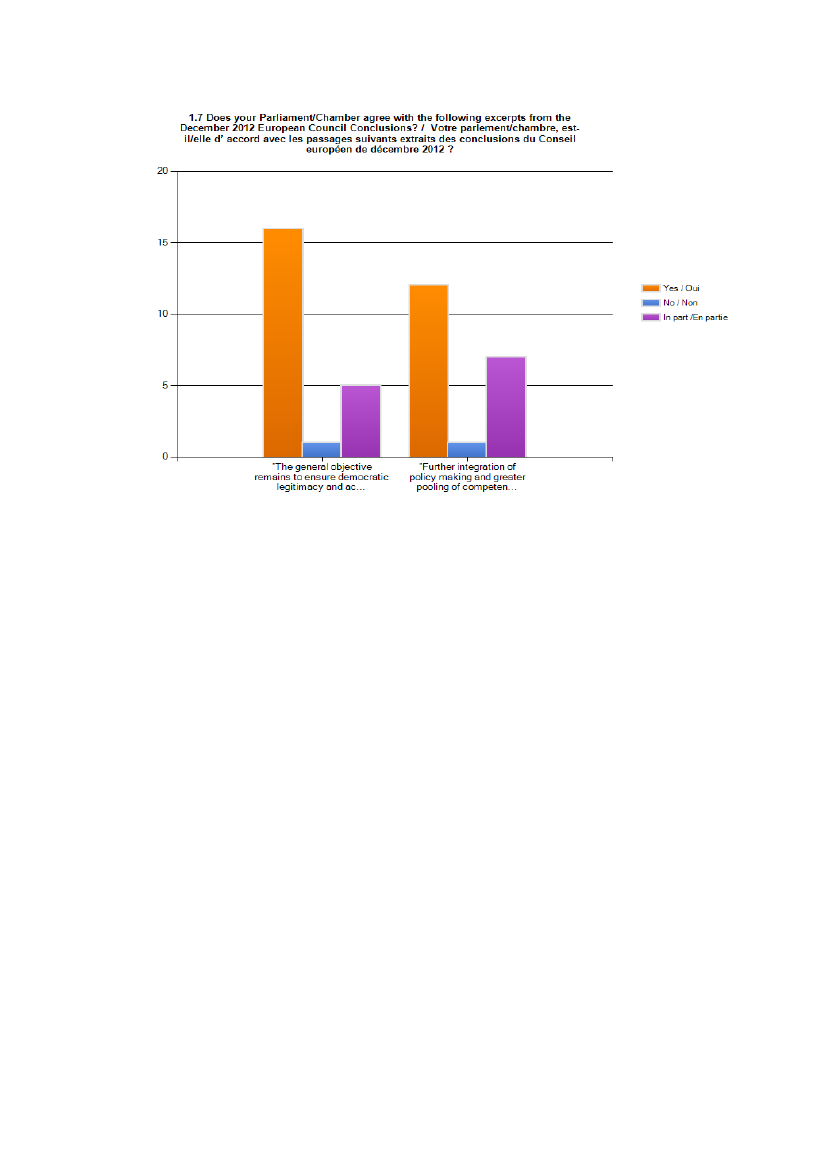

responded that the proposals were not specific enough (DanishFolketing,IrishHouses of theOireachtas,GreekVouli ton Ellinon,AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,DutchEerste Kamer,SlovenianDržavni zbor,PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicaand FrenchSénat).TheLithuanianSeimassaid it believed that the debate is wider than economic policy alone. TheLatvianSaeimanoted that none of the documents outline clear options for guaranteeinglegitimacy thus leaving it to Parliaments to decide how to become genuinely involved in thedebate.A smaller number of Parliaments/Chambers considered that the documents were a goodbase for discussion which created a framework for national Parliaments to take the matterfurther and decide for themselves (UKHouse of Lords,RomanianSenatul,HungarianOrszággyűlésand SlovakNárodná rada).The PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicasupportedthe need for national Parliaments to define how best to oversee the deepening of the EMU.Others offered proposals as to how to improve the situation; the ItalianSenato dellaRepubblicaproposed that national Parliaments could have a greater role in debating theCountry-Specific Recommendations with the Commission and Council, in the accountabilityof the ECB, in the new contractual arrangements under development and in the fiscalcapacity. The AustrianNationalratandBundesratsuggested that "national Parliamentsshould be strengthened within the European legislative process by deepening the subsidiaritycontrol mechanism (i.e. subsidiarity and proportionality check), improving parliamentaryoversight of the European Semester and giving national Parliaments the possibility to activelyinitiate European debates". The SwedishRiksdagcautioned that "several of the proposalscontained in the documents are far reaching and require treaty changes" and the AustrianNationalratandBundesratstated that democratic accountability on the European levelshould also be brought before a European Convention.1.5 December 2012 European Council Conclusions - democratic legitimacy andaccountabilityParliaments/Chambers were asked whether they agreed with the following excerpts from theDecember 2012 European Council Conclusions:1. “The general objective remains to ensure democratic legitimacy and accountability atthe level at which decisions are taken and implemented"; and2. “Further integration of policy making and greater pooling of competences must beaccompanied by a commensurate involvement of the European Parliament”.

8

In regard to the first excerpt 21 out of 22 Parliaments/Chambers (95.4%) mentioned thatthey were in favour or partly in favour as long as competences remained where theycurrently are; for example, the DutchEerste Kamerstated that the approval of a nationalbudget is ultimately the prerogative of the national Parliament. The PortugueseAssembleiada Repúblicasaid that the level where a decision was made does not always coincide withthe level where that decision is implemented and so argued that democratic legitimacy andaccountability should go across several levels. The UKHouse of Lordsresponded that, if therewas a move to more decision making at an EU level or on the basis of inter-governmentalagreements outside the framework of the Treaties, there may be a case for facilitatinggreater involvement of national Parliaments than currently exists at an EU level. The FrenchSénatdid not agree with the first excerpt and argued that, in reality, European and nationallevels are now closely interdependent, while the DutchTweede Kamerand the DanishFolketingargued that the role of national Parliaments must be strengthened as they are closeto their citizens.Nineteen out of 20 Parliaments/Chambers (95.0%) were in favour or partly in favour of thesecond excerpt. Some of these Parliaments/Chambers emphasised the importance of a broaddebate among and the key role of national Parliaments in subsequent procedures. TheLithuanianSeimassaid that there is a need to ensure an effective dialogue between all thenational Parliaments and the European Parliament. The RomanianCamera Deputaţilorcautioned there should be no competition in terms of legitimacy between nationalParliaments and the European Parliament.The Parliaments/Chambers which partly agreed with the second excerpt (7 or 35.0%) statedthat it is not only the European Parliament but national Parliaments too that must beinvolved, this is especially true for matters within their reserved competence. The German9

Bundestagemphasised that legitimacy should follow competences and that, therefore, aclear assignment of competences was necessary. The RomanianCamera Deputaţilorarguedthat more stringent fiscal rules were making the process more invasive in terms of nationalsovereignty and, therefore, greater legitimacy was being sought.The UKHouse of Commonsdid not agree with the second excerpt and with the statement ofthe Commission that it is only the European Parliament that can provide democraticlegitimacy for the EU and, therefore, the euro. It pointed out that any parliamentaryoversight of a strengthened EMU should be at the level of 27 national Parliaments and theEuropean Parliament; and any new arrangements must respect the different competences ofnational Parliaments and the European Parliament and operate consistently with nationaldemocratic scrutiny processes.Many Parliaments/Chambers emphasised that, in practice, the statements could beimplemented by creating appropriate parliamentary structures wherein both nationalParliaments and the European Parliament are represented. The effective implementation ofArticle 13 of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic andMonetary Union and Protocol No 1 to the Lisbon Treaty could show how to put thesestatements into practice. The CyprusVouli ton Antiprosoponsaid that the statements couldbe achieved in practice through strengthening democratic legitimacy of the EuropeanSemester process as well as through strengthening cooperation between nationalParliaments and the European Parliament. It also said that the European Parliamentary Weekon the European Semester for Economic Policy Coordination, the COSAC and the PoliticalDialogue with the Commission contribute towards ensuring democratic accountability andlegitimacy. The European Parliament answered when new competences are transferred to orcreated at Union level or when new Union institutions are established, a correspondingdemocratic control by, and accountability to, the European Parliament should be ensured7while the SlovakNárodná radaemphasised that strengthening the role and increasing thecompetences of the European Parliament must be accompanied by increasing the EuropeanParliament’s direct political responsibility for its decisions.Some Parliaments/Chambers suggested concrete steps for strengthening the role of nationalParliaments in European decision-making. For instance, the RomanianSenatulsuggested thatdemocratic legitimacy and accountability in the case of the national parliaments may beenhanced through a stronger involvement of the Parliament, at the national level, regardingthe European Semester, National Reform Programme and Council recommendations, whilethe DanishFolketingsuggested establishing a right of initiative for national Parliaments inparallel to a citizens’ initiative (a certain number of national Parliaments should be allowed toinvite the European Commission to consider tabling a legislative proposal) in order tostrengthen national Parliaments in European decision-making. Another idea proposed by theDanishFolketingwas for political opinions to undergo the subsidiarity check procedure andobtain the same status as reasoned opinions thereby strengthening the Political Dialoguewith the Commission.

7

A specific part of the Thyssen report is dedicated to this topic (part 4: "Strengthening democratic legitimacy andaccountability"):http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?type=TA&reference=P7-TA-2012-0430&language=EN&ring=A7-2012-0339

10

1.6 Parliamentary preparation for European Council meetings and scrutiny of EuropeanCouncil conclusionsAt least 23 Parliaments/Chambers scrutinise the European Council meetings and/orconclusions in some way.Procedures differ among Parliaments/Chambers; nevertheless some similarities and trendscan be identified. Debates are organised before and after the European Council meetings inmany Parliaments/Chambers. Debates usually take place within committees and less often inplenary sessions. The Prime Minister (usually alone or accompanied by a Minister) attendsthe debates in the majority of Parliaments/Chambers. Policy-setting documents may beapproved during meetings held to debate the conclusions of the European Council meeting.Governments give feedback on the conclusions adopted by the European Council irregularly(usually when the issue can fundamentally affect states’ interests) at someParliaments/Chambers.Where do debates take place?According to the responses given to the questionnaire, at least 13 out of 32Parliaments/Chambers answered that prior to and/or after European Council meetingsdebates take place only within committee(s). In many of these Parliaments/Chambers,Committees on European Affairs play the key role and debate European Council meetingsand/or their conclusions. Other committees can also be involved (for instance, Committeeson Foreign Affairs, Committees on Finance, etc.). The HungarianOrszággyűlésrespondedthat prior to a European Council meeting a special forum called the European UnionConsultation Body is convened by the Speaker in order to provide a forum for a dialogue onEU matters between the Government and the Parliament.8At least 11 Parliaments/Chambers said that prior to and/or after European Council meetingsdebates take place within plenary sessions. Four of these Parliaments/Chambers indicatedthat before European Council meetings they hold plenary debates to discuss the position thatthe Government will take during the forthcoming European Council meeting; and seven ofthese Parliaments/Chambers hold plenary debates afterwards on the results of the EuropeanCouncil meetings.The responses of two Parliaments/Chambers (RomanianCamera Deputaţilorand CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon)characterised the degree of influence that can be formally exercisedover the actions as limited due to the nature of their presidential democracy systems.When are debates organised?More than half (some 17) of Parliaments/Chambers remarked that debates are organisedbefore and after European Council meetings. Three Parliaments/Chambers said that thegovernment reports to the Parliament/Chamber on the outcome of a European Councilmeeting within a certain period (one week in Ireland and fifteen days in Italy).

8

The Speaker, the Deputy Speaker, the leaders of parliamentary factions (political groups), the Chairman and Vice-chairmanof the Committee for European Union Affairs, the Chairman of the Committee for Foreign Affairs and the Chairman of theConstitutional Affairs Committee are members of the Body.

11

Six Parliaments/Chambers (for instance, the DutchTweede Kamerand GermanBundesrat)intheir answers said that debates on the results of European Council meetings are heldoccasionally or not on a regular basis.Four Parliaments/Chambers responded that European Council conclusions are notscrutinised. For instance, the EstonianRiigikoguemphasised that it is the Government’s dutyto monitor whether the conclusions are in compliance with the Estonian positions. TheSlovenianDržavni zborstated that after European Council meetings the Government onlysends it reports on the debates and conclusions of the meetings.The European Parliament responded that it regularly prepares for European Council meetingsin its plenary sessions. The President of the European Parliament is also invited to addressEuropean Council meetings and the President of the European Council is obliged to reportback to the European Parliament after each European Council meeting.Who represents the Government in the debates?The majority of Parliaments/Chambers responded that their Prime Minister attends thedebates usually alone or accompanied by a Minister. Some Parliaments/Chambers (forinstance, the PortugueseAssembleia da República)responded that plenary debates heldprior to European Councils are attended by the Prime Minister only, while meetings whichare held to debate the conclusions of the European Council are attended by the Secretary ofState for EU Affairs. For example, the Slovak, Lithuanian, Belgian Prime Ministers usuallypresent the positions, prepared by the Government, to the Parliament/Chamber. The GreekVouli ton Ellinonheld hearings with keynote speakers from the competent ministries.Debates before the European Council are followed by the approval of positions prepared bythe government in some Parliaments/Chambers (for instance, the ItalianCamera deiDeputati,LithuanianSeimas)and sometimes policy-setting documents such as resolutionsand motions may be approved during meetings held to debate the conclusions of theEuropean Council meeting.

12

CHAPTER 2: EUROPEAN SEMESTER 2013The European Semester, the annual cycle of EU level surveillance and coordination ofMember States’ fiscal, economic and structural reform policies is now in its third year. Whilethe process has been bedding down at EU level, it has been largely dominated by theCommission and the Council to date, with the European Parliament and national Parliamentsstruggling to define their role in the new and rapidly evolving economic governance of theUnion.At national level, Parliaments/Chambers can obviously play a critical role in ensuringappropriate and timely oversight of government inputs at key points during the period of theEuropean Semester process and subsequently, as well as debating relevant EU level growthforecasts, guidance and Country-Specific Recommendations.At European level, oversight by the European Parliament, together with greaterinterparliamentary cooperation with national Parliaments will be crucial to underpin theEuropean Semester process. The European Parliament organised a Parliamentary Week onthe European Semester in January 2013, involving its relevant committees andrepresentatives from equivalent committees of national Parliaments, to promoteinterparliamentary cooperation and specifically to stimulate debate and parliamentaryinvolvement in the European Semester in 2013.This section of the Report will seek to analyse information from Parliaments/Chambers ontheir involvement in the European Semester in 2013 at national level, particularly in relationto scrutiny of the Annual Growth Survey (AGS) 2013, the relevant draft Stability andConvergence Programmes (SCP), National Reform Programmes (NRP), and Country-SpecificRecommendations (CSR), as well as summarising their views on the substance of thesedocuments, the overall economic governance process, and how it might be improved upon.2.1. Engagement in the economic governance of the EU and the European Semester atnational level in 2013.When all Parliaments/Chambers were asked whether they were satisfied with the degree ofengagement in the economic governance of the EU and the European Semester at nationallevel in 2013, out of 28 Parliaments/Chambers that answered this question, 24 said that theywere satisfied or partly satisfied, while 4 were not. The majority of nationalParliaments/Chambers stated that they had debated the AGS, the NRP and/or the SCP, aswell as the CSR and that they would continue to debate these matters in their relevantcompetent committees and/or with their government. Two Parliaments/Chambers hadadditionally scrutinised the Alert Mechanism Report (DutchEerste Kamerand UKHouse ofLords).In subsequent comments Parliaments identified the improvements they thought werewarranted i.e. a more timely consideration of the documents (LatvianSaeima,PolishSejmand DutchTweede Kamer),consideration of the documents before they were issued to theCommission (EstonianRiigikogu,AustrianNationalrat,CzechSenátand PortugueseAssembleia da República),the need to be able to amend the documents (FrenchAssembléenationale),the need to develop a separate specific parliamentary procedure to integrate it13

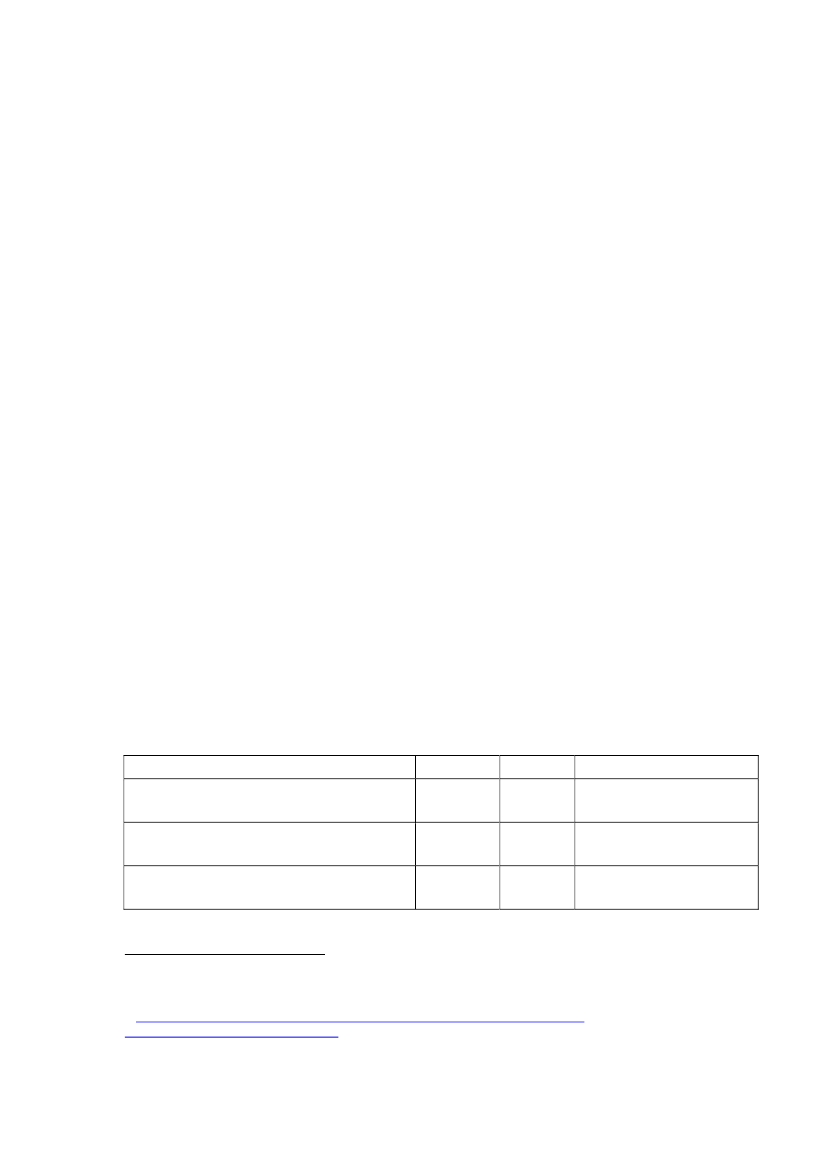

into parliamentary life (DutchEerste Kamer,BelgianChambre des représentantsandSénat,the IrishHouses of the Oireachtasand RomanianCamera Deputaţilor)and the need to reviewthe content and substance of the key documents. The GermanBundesratdisagreed thateducation policy should be part of the CSR. The European Parliament noted that in manyresolutions it had called for the strong involvement of national Parliaments/Chambers in theSemester Cycle.2.2. Scrutiny of Annual Growth Survey 2013.The majority of national Parliaments/Chambers (24 out of 34) had debated/scrutinised theAGS 2013. The European Parliament adopted two own-initiative reports on the AGS 2013 andcalled for the AGS to be subject to the co-decision procedure. In addition, within the contextof the economic dialogue, the European Parliament planned to conduct two dialogues, onewithin the framework of the European Semester in April and another scheduled in June onCSR.Some of the procedural steps employed by Parliaments/Chambers to scrutinise the AGSincluded the following: UKHouse of Lordsissued a letter to the relevant minister; thePortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicaissued a report on the AGS; a numberParliaments/Chambers discussed the AGS in the European Affairs Committee (AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,GermanBundestag,LithuanianSeimas,PolishSejm,SlovenianDržavni svetand SpanishCortes Generales)or Finance Committee (IrishOireachtas)or othercommittee (UKHouse of Commons);some Parliaments/Chambers questioned Ministers andPrime Ministers (including the DanishFolketing);a few brought the matter to plenary for adebate or adoption of a resolution (AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,DutchEerste Kamerand CzechSenát);and the LatvianSeimasadopted a decision recommending theGovernment to align its position on the AGS.In the DanishFolketingthere is a well ordered parliamentary procedure, parts of which areevident in many other but not all Parliaments/Chambers and under which the relevantministers appear before the European Affairs Committee prior to discussions in the Councilon different parts of the Annual Growth Survey. The Prime Minister appears before theEuropean Affairs Committee prior to and again after the European Council spring meetingswhere the Annual Growth Survey is endorsed. Likewise government representatives presentCountry Specific Recommendations prior to Council meetings and European Council meetingin June. A draft plan for a national semester envisages improving the procedure by having agovernment representative appear at joint meetings between Finance Committee andEuropean Affairs Committee three times during the semester: 1) in December when theAnnual Growth Survey is launched, 2) in March before the government submit the NationalReform Programme and the Convergence Report to the Commission, 3) by the end of Maywhen the Commission give country specific recommendations.2.3. Scrutiny of Documents in 2013A summary of the responses of national Parliaments/Chambers can be seen below in relationto their plans to scrutinise key documents in 2013. It is clear that there is a high level ofscrutiny either ex-ante or ex-post and that less than one fifth of respondents did notscrutinise them.

14

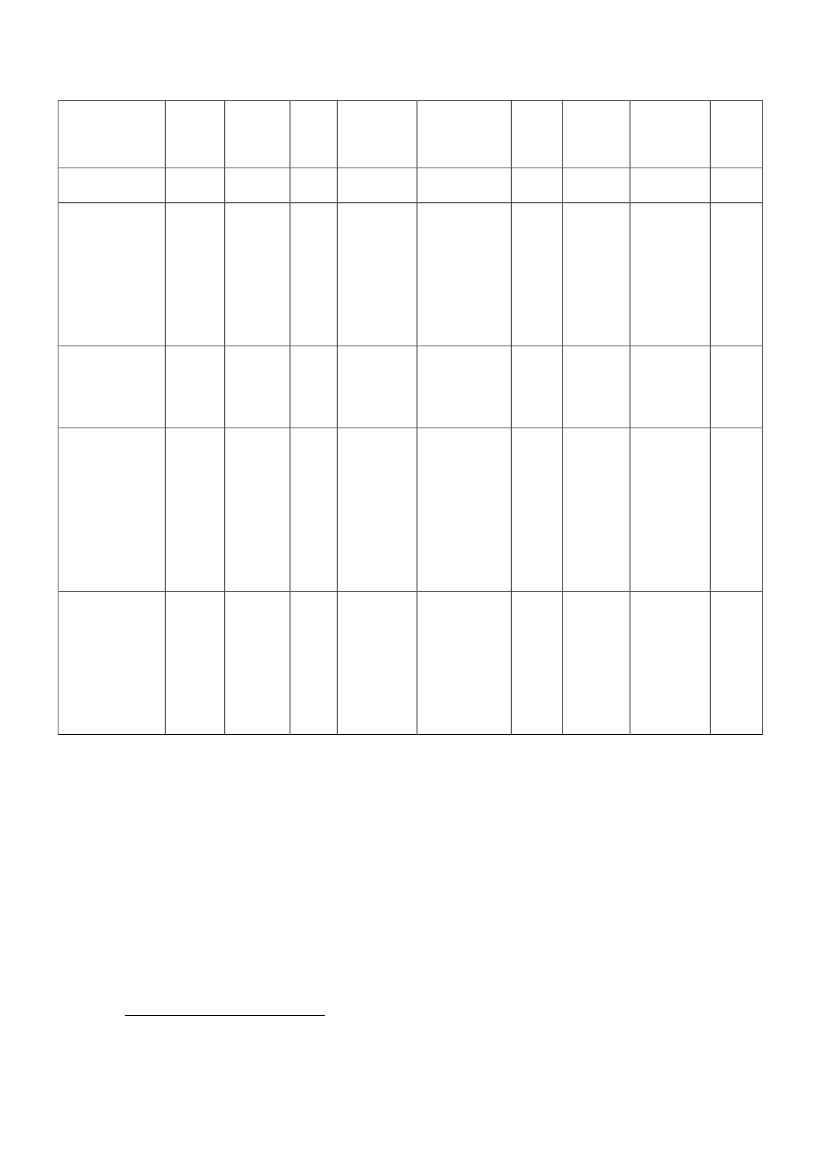

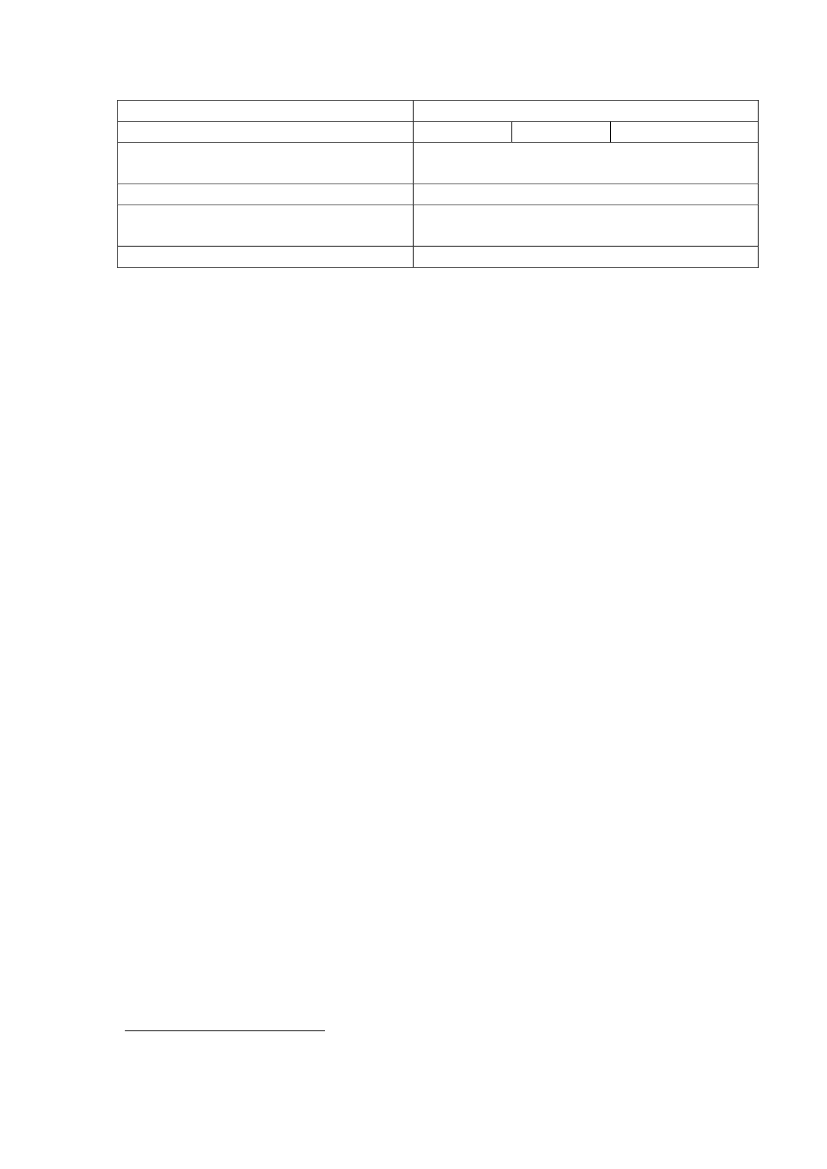

Draft Stability andConvergenceNational ReformProgrammeCountry-SpecificRecommendations

Yes(ex-ante)19(59.4%)918(56.3%)15(48.4%)

Yes(ex-post)8(25.0%)10(31.3%)11(35.5%)

No5(15.6%)4(12.5%)5(16.1%)

Total No. of Responses323231

The SpanishCortes Generalesadded that the above documents were subject to scrutiny, viahearings held by members of the government prior and post the European Council, both atPlenary and committee level and may result in different initiatives (written questions, nonlegislative resolutions, interpellations (a form of plenary debate)). It added that the SCP andthe NRP were also the subject of anad hochearing held in theCongreso de los Deputaţadoson the 8th May 2013, in which the Prime Minister appeared before the plenary. The SlovakNárodná radafurther noted that with regards to the CSR, it "considers ex-ante/ex-postdebate/scrutiny formulation in relation to the CSRs as unclear" and that the relevantCommittee debates the CSR before meetings of the Council of the EU and the EuropeanCouncil in June. The European Parliament also noted that the competent committeeorganised economic dialogues with other EU institutions, as part of the "comply or explain"principle.2.4 Role of Committees in preparation of key documentsA majority of 20 of the 34 Parliaments/Chambers responded that their committees werealready involved in the preparation of the SCP, NRP and the CSR and threeParliaments/Chambers foresaw future involvement.Some of the notable mechanisms for committee involvement included:The LithuanianSeimascommittees discussed the draft documents extensively andhave the right to recommend amendments that the Government is obliged to includein the drafts.In the SlovenianDržavni zborthe [European Affairs] Committee and the sectoralcommittees may choose to adopt opinions on drafts which might be included in theSCP and NRP.The RomanianSenatul'sCommittee on EU Affairs coordinated a debate regarding theEuropean Semester, the AGS, the NRP and the SCP, in March 2013.The European Union Affairs Committee of the PolishSejmholds a debate on CSRspursuant to the Act of 8 October 2010 on the cooperation of the Council of Ministerswith theSejmand theSenatof the Republic of Poland in matters relating to theRepublic of Poland's membership in the European Union.The FrenchSénatreplied that in future the organisation of debates on these subjectsis prescribed by law. This obligation has been respected in 2011, but not in 2012 dueto the national elections which caused an interruption of parliamentary work.

9

Percentages given are calculated as a percentage of the total respondents to each question or part thereof. This does notrepresent a percentage of Parliaments/Chambers.

15

The Swedish Government is obliged to consultRiksdagen'sCommittee on EU Affairseach time the European Semester appears on the Council’s agenda for a discussion ora decision and is given a mandate to negotiate the Swedish position on the matter.The Government presents the SCP and the NRP in the Committee on Finance.

At the same time some Parliaments/Chambers replied that their committees did "notparticipate in such procedures".10The European Parliament answered that it organises anexchange of views on CSR annually and it "may invite Member States to a dialogue onnational reforms and measures that may have a clear spill-over effect to other MemberStates [or] on the EU as a whole".2.5. Engagement of national Parliaments/Chambers with the European Commission in theEuropean Semester processIn response to the degree of engagement of national Parliaments/Chambers with theEuropean Commission in the European Semester process, 17 out of 34Parliaments/Chambers answered that that they had engaged with the European Commissionin some part of the process. These Parliaments/Chambers had direct communication with aCommissioner, the Commission Representation in capitals or staff from Brussels who hadparticipated in a debate held in the relevant committee (PolishSejm,ItalianCamera deiDeputatiandSenato della Repubblica,11SwedishRiksdagand BelgianChambre desreprésentants)or envisage a discussion taking place before the publication of CSR (FrenchAssemblée nationale and the European Parliament).Other ways of engaging included theinformal sharing of the relevant ministerial correspondence with the European Commission(UKHouse of Lords)the issuing or a reasoned opinion to the Commission (PortugueseAssembleia da República).2.6. Increased participation of Parliaments/Chambers in the European Semester since theprocess began in 2011The majority of national Parliaments/Chambers (23 out of 33) answered that theirparticipation in the European Semester had increased since the process began in 2011.According to the replies to the questionnaire, this increase mainly entailed activeparticipation in interparliamentary meetings on the European Semester and debates atcommittee level. Ten national Parliaments/Chambers noted that the level of engagementwas the same and/or their procedure had not changed. A number of the nationalParliaments/Chambers whose engagement had increased, have specifically noted examplessuch as the following: the publication of a specific report which considered the EuropeanSemester process (UKHouse of Lords),briefings by members of the PermanentRepresentation to the European Union were organised "with a view to explaining the processof the European Semester process to the parliamentarians, while highlighting its impact atnational level" (BelgianChambre des représentants),the appointment of a rapporteur forthe European Semester to coordinate the DutchTweede Kamer´sposition in theinterparliamentary week and in the various relevant committees during the preparation ofGreekVouli ton Ellinon,UKHouse of Lords,AustrianNationalratandBundesrat,CypriotVouli ton Antiprosopon,DanishFolketing,IrishHouses of the Oireachtas11The ItalianSenato della Repubblicahas noted that the information in this chapter refers to practices and political positionsexpressed during the previous parliamentary term of 2008 - 2013, meaning that these positions may be subject to change bythe new parliament.10

16

various council meetings. The European Parliament noted that the establishment of aworking group on the European Semester ensured continuity and follow-up on the EuropeanSemester. The FinnishEduskuntanoted that while it had not changed the qualitativerelationship between it and the government, in quantitative terms the number of descriptivedocuments available from the government had increased.The European Parliament further noted that the European Parliamentary Week had enabledrepresentatives of national Parliaments/Chambers and representatives of the EuropeanParliament to discuss the main priorities of the next Semester Cycle.2.7. European Parliamentary WeekThirty-two out of 37 Parliaments/Chambers said that they had participated in the EuropeanParliamentary Week (EPW) on the European Semester in January 2013. Of these, 10 foundthat the EPW had enhanced their involvement in the European Semester, while 19 otherParliaments/Chambers answered that it had not. Of this latter group a small number of themsaid that, although the EPW did not enhance their involvement they noted its importance asa platform to share views and experiences (EstonianRiigikogu),that it provided an additionalsource of background information for the participants (HungarianOrszággyűlésand FinnishEduskunta)and that it contributed to a better awareness and understanding of the EuropeanSemester stages (GreekVouli ton Ellinon).The IrishHouses of the Oireachtascommentedthat the EPW was informative and increased the level of awareness of the European-leveldebate, but that it was, however, perceived as a "stand-alone event and did not translateinto greater involvement". Other Parliaments/Chambers answered that they had begun toreflect on the impact of the EPW (ItalianSenato della Repubblica),that the "involvement atnational level cannot be clearly identified" (GermanBundesrat)and that the impact of theinvolvement had not yet been decided as "the debate is ongoing" (CypriotVouli tonAntiprosopon).Further replies expressed that there was a "lack of opportunities for a dialogue and debatewith the Presidents of the European Union Institutions" (CzechPoslanecká sněmovna)or thatthere was a lack of genuine dialogue on the semester-related topics with the "EUrepresentatives showing up only to read their short speeches and then leaving the eventwithout engaging in any dialogue with national Parliaments" (CzechSenát).Sixteen out of 27 national Parliaments/Chambers thought that the EPW facilitated inter-parliamentary dialogue at European level on key questions pertaining to the EuropeanSemester in 2013.Some of these expressed the view that the EPW was an appropriate forum for dialogue atEuropean level. They commented that it offered parliamentarians a forum to exchange bestpractices and fostered inter-parliamentary debate on the different procedures applied toscrutinise the European Semester in national Parliaments (SpanishCortes GeneralesandHungarianOrszággyűlés)and that it was a "valuable set of meetings which allowed dialogueand networking between parliaments" (UKHouse of Lords).The SlovakNárodná radaanswered that the EPW contributed to the selection of key topics and themes to bepresented and debated at national level and the PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicastated

17

that the exchange of experience between Parliaments proved to be "an unquestionable assetin [the] scrutiny of the Annual Growth Survey".However, a number of Parliaments/Chambers were critical of the EPW and/or said thatimprovements were needed to be made to it. Specifically, the CzechPoslanecká sněmovnasaid that the organisation was "very chaotic and as a result very unsatisfactory in all aspects",the GermanBundestaganswered that there was "too little opportunity for real discussionamong parliamentarians". The AustrianNationalratandBundesratnoted that, although theEPW facilitated dialogue, the position of the governing parties (SPÖ (S&D) and ÖVP (EPP))was that earlier timing of the conference with a clear structure and agenda would have beenvery helpful. It further noted that "the establishment of the conference as foreseen by Article13 of the TSG could inter alia fulfil this role". The FrenchSénatdeplored the fact that thedebates were simply a juxtaposition of speeches and regretted that they did not lead toconclusions. The DutchTweede Kamermentioned that, although the EPW facilitateddialogue, meetings of this type tended to result in "unrelated monologues". They wanted tomake the number of delegates smaller or use parallel part-sessions or working groups and toreduce the role of Members of European Parliament. They expressed disappointment for thelack of dialogue with Presidents of the European Commission and the European Council who"both left the conference after their speech". The FrenchAssemblée nationalesaid that toget beyond the level of polite small talk the themes for the conference should be chosen bythe Parliaments together and the outcomes would depend on the quality of the preparatorywork done by each Parliament.The European Parliament expressed the view that both the European Parliament andnational Parliaments had complementary roles to play within the framework of the EuropeanSemester and that in this respect, the EPW aimed to discuss the various priorities and policiesunder the European Semester and learn from each other's experiences in improving andimplementing them.2.8 Optimum forum for interparliamentary cooperation at European level on the EuropeanSemesterThirty-six Parliaments/Chambers responded to the question of the optimum forum forinterparliamentary cooperation at European level on the European Semester. The responseswere varied with some Parliaments/Chambers supporting the European Parliamentary Weekand many supporting the idea of an interparliamentary conference while others wereproposing the use of existing fora or a combination of existing fora. SixParliaments/Chambers replied that the issue was still under consideration or that no formalposition had been adopted (though two of these made comments with this caveat in place).12The European Parliament replied that it wanted to see reinforced interparliamentarycooperation "based in existing EU procedures". It said that the activities should be timelyfrom both a European and national perspective and should be devised by the EuropeanParliament and national Parliaments together. A number of national Parliaments/Chamberscalled for the use of existing structures or fora in principle, including the IrishHouses of theOireachtas,replying that, at administrative level, consideration is being given to "idea of a12

GermanBundesrat,CzechPoslaneckásněmovna,LithuanianSeimas,SwedishRiksdag,UKHouse of CommonsPortugueseAssembleia da República(the latter two also made comments with this caveat)

18

consecutive COSAC Chairpersons and Article 13 TSG Conference, held in the same location,with the latter replacing the existing Finance Chairpersons meetings". FiveParliament/Chambers suggested the possible use of various existing fora such as the"[European] Parliamentary Week, COSAC, the meeting of the relevant committeechairpersons or IPEX" (HungarianOrszággyűlés).The FinnishEduskuntastated that "anyinterparliamentary cooperation should preferably be combined with or replace some existinginterparliamentary meeting" and the DutchTweede Kamersaid that "no new institutionsshould be set up".A number of Parliaments/Chambers identified "an interparliamentary conference" on Article13 TSCG as the optimum forum. These included (some of) the Parliaments/Chambers whichmet in Luxembourg on 11 January 2013 and issued a "working paper".13Others supportedthe concept of an interparliamentary conference included SlovakNárodná rada,PortugueseAssembleia da República,and the PolishSejm.14A number of Parliaments/Chambers supported the continuation of the EuropeanParliamentary Week (EPW), organised by the European Parliament, as the optimum forum.This included the CyprusVouli ton Antiprosopon,the PolishSenat,the RomanianSenatul(which also said "in the frame of the Article 13 of the Treaty on stability coordination andgovernance and an option might be the extension of COSAC attributions"). The CzechSenát,though it did not exclusively support the EPW, suggested a number of improvements thatcould be made to it such as the use of smaller workshops, the adoption of a resolution andthe presence of representatives from the EU institutions throughout the whole event. The UKHouse of Lordsexpressed the view that "the forum provided by the Parliamentary Weekworked very well but decisions on the optimum forum need to be taken in the right way – bycollective agreement between parliaments".The questionnaire replies predated the meeting of the Conference of Speakers of EU Parliaments,held in Nicosia on 21-23 April 2013, which agreed on the establishment ofa Conference, in line

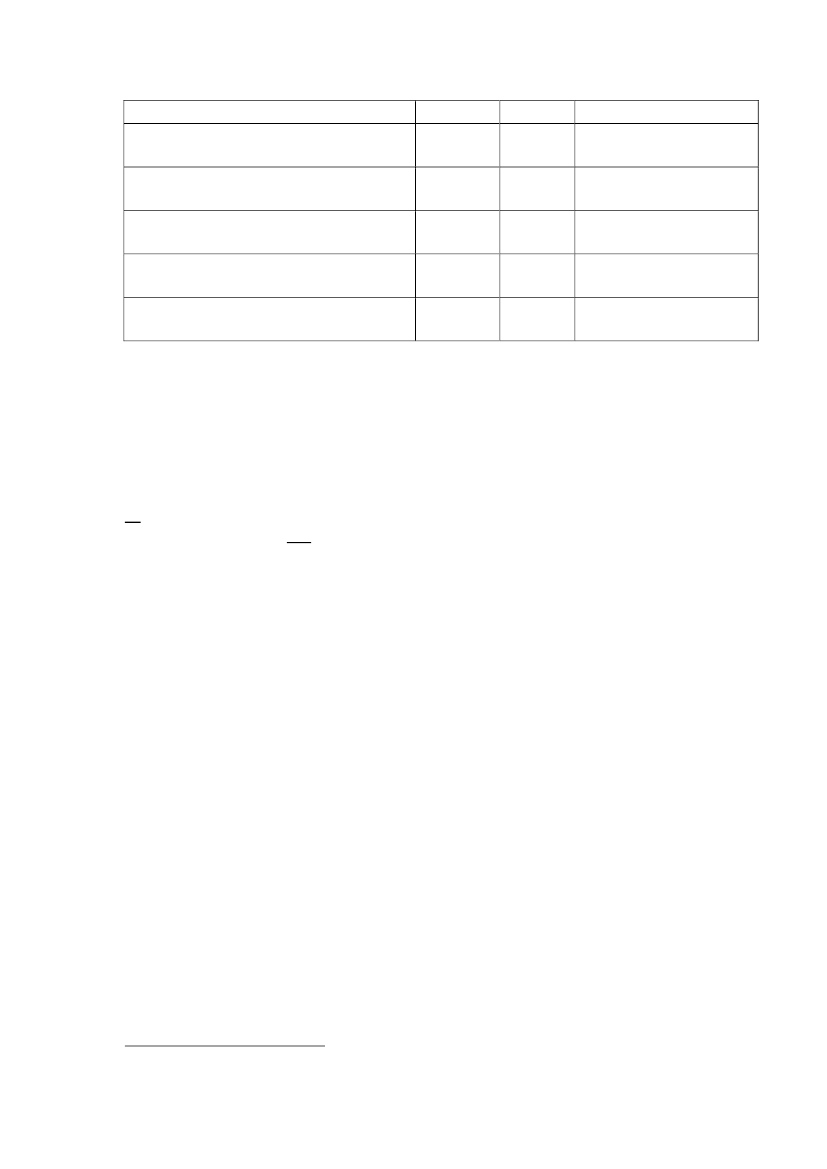

with Article 13 of the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance in the Economic andMonetary Union, building on established structures for interparliamentary cooperation.2.9 Changes to procedures at national level in response to the European SemesterYesChanges alreadymade to nationalproceduresChanges to nationalprocedures planned9(27.3%)12(38.7%)No24(72.7%)19(61.3%)Total No. of responses3331

The summary of responses above shows that eight Parliaments/Chambers answered thatthey had already changed parliamentary procedures and 12 said they foresee a change due13

Working paper of the meeting of the Speakers of Parliament of the Founding Member States of the European Union andththe European Parliament in Luxembourg on January 11 , 2013. The ItalianCamera dei Deputatidid not participate in themeeting and does not endorse the working document.14As did the FrenchAssemblée nationalewho adopted a resolution on the matter on 27 November 2012.

19

to the European Semester (four of these answered "yes" to both categories). Changes thathad already been made included, for example: in the GreekVouli ton Ellinonthe creation ofthe State Budget Office and an enhancement of the Parliament’s relations with the GreekCourt of Audit and organisation of public hearings; in Italy the amendment of Law no.39 (7April 2011) included the obligation for the government to forward "the acts, draft acts anddocuments adopted by the EU institutions in the framework of the European semester" tothe two chambers of the Italian Parliament and the "Economy and Finance Minister willreport to the appropriate parliamentary committees...also with a view to the development ofthe Stability Programme and the NRP" and other provisions; in the FrenchSenátthe changetook the form of the organisation of debates, provided for by law; the amendment of theBudgetary Framework Law in 2011 in the PortugueseAssembleia da Repúblicato considerthe Stability and Growth Programme (SGP) at the start of the internal budgetary process andto make mandatory the plenary debate on the SGP and; consultation of the GermanBundestagprior to the submission of the NRP and SGP.The changes foreseen by Parliaments/Chambers included:A draft plan for a national semester (mentioned earlier) envisaged improving theprocedure by having a government representative appear at joint meetings betweenFinance Committee and European Affairs Committee three times during thesemester: 1) in December when the AGS is launched, 2) in March before thegovernment submits the National Reform Programme and the Convergence Report tothe Commission, 3) by the end of May when the Commission gives CSR (DanishFolketing).SCP to be discussed in Parliament before it is sent to the European Commission(DutchTweede Kamer).A proposal to harmonise the schedule under which the Government will submit thedrafts of the NRP and the SCP to the Parliament, allowing reasonably sufficient timefor parliamentary scrutiny (LithuaniaSeimas).The Draft Law on Cooperation between the Parliament and the Government inEuropean Affairs, in the final stage of adoption in the Senate, contains provisions onthe parliamentary action in all phases of the European Semester (RomanianCameraDeputaţilor).

20

CHAPTER 3: EUROPEAN UNION ENLARGEMENTThe European Commission published its most recent annual Communication on EnlargementStrategy in October 2012.15Council conclusions from December 2012 highlighted the needfor a credible enlargement policy to maintain reforms in the countries concerned and forpublic support for enlargement in Member States.16Following the anticipated accession of Croatia to the EU on 1 July 2013, there is no clearcandidate state that is next in line to join the Union. This fact, coupled with so-called“enlargement fatigue”, whether real or perceived, holds the prospect that momentum forreform in candidate states and potential candidate states may be lost.Parliaments play a key role in the enlargement process in the EU in terms of debate andratification of accession treaties, scrutiny of stabilisation and association agreements,facilitation of dialogue with state and civil society actors in candidate countries and potentialcandidate countries and for communicating the case for enlargement to citizens.This section of the Report contains information on the practices and procedures withinParliaments in relation to the enlargement process, views on the most recent EnlargementStrategy, dialogue with political, official and civil society representatives in enlargementstates, and the role of Parliament in the national discourse on enlargement.3.1 Practices and procedures within Parliaments in relation to the enlargement processThe introductory question asked in this chapter was what form the parliamentary approval ofAccession Treaties and Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAAs) takes inParliaments/Chambers. In most cases an Act of parliament was reported to be needed (30out of 35 respondents).17In some cases, however, an Act of Parliament as such is notsufficient: in France draft laws authorising the ratification of a treaty of accession are inprinciple subject to a referendum, except if both Chambers adopt a motion by a two thirdsmajority to submit the question to theCongrés.In the United Kingdom, three requirementsfor approval had to be met: a ministerial statement as to whether the treaty triggers areferendum under the European Union Act 2011; an Act of Parliament approving the treatyand; compliance with either the referendum condition or exemption condition are necessary.This does not apply to SAAs which are scrutinised at committee level but do not require anAct of Parliament. In Sweden, in addition to the decision of theRiksdagon the accessiontreaty, a revision of the Swedish act on accession was required. Only following the consent ofthe European Parliament to Agreements by means of a legislative resolution can therespective agreements be signed and their ratification procedure by EU Member States andthe country concerned launched.

1516

http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/key_documents/2012/package/strategy_paper_2012_en.pdfhttp://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/EN/genaff/134235.pdf17The Polish Sejm replied 'no'. "However, the European Union Affairs Committee discussed, for example, theCommunication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on a Feasibility Study for a Stabilisationand Association Agreement between the European Union and Kosovo [COM(2012) 602 final]."

21

3.2 Monitoring reports, annual progress reports and the enlargement strategyTwenty-one Parliaments/Chambers reported regularly debating and/or scrutinisingmonitoringreports (on acceding countries) and 20 out of 34 Parliaments/Chambers reporteddebating and/or scrutinisingannual progressreports (on candidate and potential candidatecountries).18While most of the Parliaments/Chambers that responded either debated orscrutinised both kinds of reports (19 out of 21 which replied positively regarding monitoringreports), a number had not debated them (14 out of 15 gave a negative reply). The EUCommittee of the LatvianSaeimaconsiders these reports if "relevant discussions [ordecisions] are expected at the EU Council".When asked whether they debated the most recent Commission Communication setting outan Enlargement Strategy and the Main Challenges 2012-2013,1918 Parliaments/Chamberssaid they (already) had, while an equal number replied in the negative. In most of theParliaments/Chambers which provided additional information the discussion on thisCommunication was limited to the level of EU Affairs Committees. Two Chambers dealt withthe enlargement strategy in plenary: the RomanianCamera Deputaţilorand the CzechSenát(which adopted a resolution). It should be mentioned that even though they did not answerthe question in the positive, three Parliaments/Chambers held discussions in their respectivecommittees on enlargement in general terms (the IrishHouses of the Oireachtasand the UKHouse of Commons)or took note of the Commission Communication (the SpanishCortesGenerales).The EU Committees of the GermanBundestagand the FrenchSénatdiscussedthe reports and the Enlargement Strategy with Enlargement Commissioner Füle. On 22November 2012 the European Parliament adopted a resolution on "Enlargement: policies,criteria and the EU’s strategic interests", which put forward a number of recommendationsfor the future of the Enlargement policy.20The replies from the PolishSejm,RomanianCamera Deputaţilorand the SlovenianDržavni zborexplicitly mention their Committee'ssupport for the enlargement process and the latter two called for an intensified and betterenlargement communication strategy in the EU.Parliaments/Chambers were also asked to provide details on whether they discussedenlargement in relation to individual candidate and potential candidate countries. Anoverview is given in the table below:YesNoTotal No. of responses286a) Turkey(82.4%)21(17.6%)342014b) Iceland(58.8%)(31.2%)342212c) Montenegro(64.7%)(35.3%)34

18

The GreekVouli ton Ellinonand the DutchEerste Kamerdiscussed just some of the countries and the SlovakNárodná radaand the SwedishRiksdagreplied they did not discuss any of them on a subsequent question.19COM (2012) 60020http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//TEXT+TA+P7-TA-2012-0453+0+DOC+XML+V0//EN&language=EN21Percentages given are calculated as a percentage of the total respondents to each question or part thereof, This does notrepresent a percentage of Parliaments/Chambers.

22

d) Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedoniae) Serbiaf) Albaniag) Bosnia and Herzegovinah) Kosovo

Yes21(61.8%)25(73.5%)21(63.6%)21(63.6%)21(63.6%)

No13(38.2%)9(26.5%)12(36.4%)12(36.4%)12(36.4%)

Total No. of responses3434333333

The replies show that in all cases a larger number of Parliaments/Chambers discussedenlargement in relation to each of the candidate and potential candidate countries than didnot. Ten Parliaments/Chambers held discussions on enlargement selectively, depending onthe country in question or whether it was a neighbouring country. However, with theexception of the GermanBundesratall of them discussed enlargement to Turkey. Other thanthis, the replies did not show any obvious patterns. Seventeen Parliaments/Chambers,including the European Parliament, declared that they debated enlargement with regards toall the countries in question while five Parliaments/Chambers responded that they did notdiscuss enlargement to any countries. In addition, the UKHouse of Commonsand the FrenchAssemblée nationalestated in replies to previous questions that they discussed both kinds ofreports on a regular basis.Seventeen Parliaments/Chambers held these discussions in their specialised European Affairsand/or Foreign Affairs committees. Three Parliaments/Chambers mentioned the adoption ofreports or resolutions, and two Chambers mentioned debates in plenary: the DutchEersteKamerexplained that "the enlargement of the EU is yearly touched upon during the debateon the policy of the government for Europe (also called State of the Union debate)", whilethe ItalianCamera dei Deputatimade reference to a plenary resolution that committed theGovernment to support the accession of Turkey to the European Union at the sameconditions as the other candidate countries.22The ItalianSenato della Repubblicasaid that it“believes that a process leading to the enlargement of the Union to all Western Balkancountries should be considered irreversible" and “reaffirms the relevance of Turkey, whoseEuropean perspectives are a powerful factor of stability and geopolitical balance in theMediterranean and the Middle East” while insisting fully on respecting the Copenhagencriteria. Other Parliaments/Chambers highlighted a generally favourable disposition towardsenlargement "provided" the candidate countries "meet the Copenhagen criteria". TheSlovenianDržavni zborstated that it "believe[s] that a positive agenda with Turkey cannotrepresent an alternative to accession negotiations".3.3 Dialogue with political, official and civil society representatives in enlargement statesAbout two thirds of the respondents answered that their Parliament/Chamber had engagedin dialogue with political, official and civil society representatives in enlargement states "on aregular basis" (24 out of 36, with 12 negative replies). The most intense and regular relations22

Approved on 7 September 2011, i.e. during the previous legislature.

23

with its parliamentary counterparts from each 'enlargement country'23were maintained bythe European Parliament, some of them based on legal provisions within the SAA: it repliedthat "the most advanced type of inter-parliamentary relationship is the Joint ParliamentaryCommittee (as in the case of Croatia, Turkey, Iceland and the former Yugoslav Republic ofMacedonia), followed by the Stabilisation and Association Parliamentary Committees (wherethe SAA is in force - Albania and Montenegro) and Inter-parliamentary Meetings (IPM - withBosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Kosovo)." The Standing Bureaus of the RomanianSenatuland theCamera Deputaţiloradopt an annual Foreign Affairs Plan which includes "actions onbilateral or multilateral level, involving adhering, candidate states, or other states with acertain accession perspective". On the other side of the spectrum someParliaments/Chambers maintained contacts rather "on an informal basis" (e.g. BelgianSénatand IrishHouses of the Oireachtas).Additional information provided by Parliaments/Chambers showed a broad variety ofdistinctive dialogue partners:some Parliaments'/Chambers' contacts were limited to the administrative level(GreekVouli ton Ellinon,BelgianChambre des représentants);ten Parliaments/Chambers predominantly engaged in discussions at the level ofpoliticians in enlargement countries;24andeight Parliaments/Chambers engaged in discussions with politicians as well as civilsociety in enlargement countries.Twelve Parliaments/Chambers mentioned missions to enlargement countries as well as thereception of visitors from candidate and potential candidate countries. SevenParliaments/Chambers reported that they received visitors from candidate and potentialcandidate countries.25The LithuanianSeimasprovided further insight into its contacts, whenit mentioned that "usually discussions on EU enlargement with politicians, officials, civilsociety, researchers and other stakeholders are...not only...open for public, but they are alsobroadcast on theSeimasTV and theSeimaswebsite", which is an interesting proposal inrelation to the following chapter.3.4 Enhancing the national discourse on enlargement in the EU Member StatesA broad variety of answers were given on the question as to how Parliaments/Chambersbelieve that the national discourse on enlargement could be enhanced in their MemberState.Parliaments/Chambers generally took one of two views: on the one hand, a status quoapproach with answers such as "this is not a political question" (FinnishEduskunta)orstatements that the respective Member State "is not against enlargement" (EstonianRiigikogu),or that "all relevant political forces" were in favour and therefore there was "noneed to enhance the discourse or to change the approach on enlargement" (Romanian2324

Including acceeding, candidate and potential candidate countries.Details of Parliaments /Chambers can be found in the appendix to this Report... The replies from the FrenchAssembléenationaleand the GermanBundesratwere not explicit as concerns the level of their contacts, but it seems they rathermaintain contacts at political level only.25The LuxembourgChambre des Députésdid not specify whether the dialogue in the framework of "parliamentary visits"took place at home or abroad.

24