Europaudvalget 2012-13

EUU Alm.del Bilag 80

Offentligt

Delivering results

– How Denmark can lead the way for Policy Coherence for Development

May 2012Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

1

AcknowledgementsThe report has benefited from the dedicated work of an internationalsteering group, which provided useful advice and comments. ConcordDenmark would like to thank the Steering Group for their time andcontributions. Please note that the conclusions and statements in thereport do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the international steeringgroup. Concord Denmark takes the full responsibility for the report.Report coordinator: Knud VilbyOverall responsibility: Laust Leth Gregersen, Adam Fejerskov and MortenEmil Hansen (Concord Denmark).Photo frontpage: POLFOTO/AP-Michel EulerGraphic Design: Ægir/KoefoedPrint: Jønsson Thomsen Elbo A/S

International steering groupEbba Dohlman:Head of the Policy Coherence forDevelopment Unit at the OECD and Senior Advisor to theSecretary-General.Each of the individual experts is responsible for their contributions to thethematic chapters:The introduction was contributed to by Knud Vilby, Laust Leth Gregersen(Concord Denmark), Adam Fejerskov (Concord Denmark) and MortenEmil Hansen (Concord Denmark).The EU Institutional Framework chapter was contributed by Niels Keijzer(ECDPM)The thematic chapter on Biofuels was contributed by Knud VilbyThe thematic chapter on Illicit Financial Flows was contributed byRaymond W. Baker (Global Financial Integrity). Sarah Johansen (ConcordDenmark) has contributed with vision and objectives.The thematic chapter on Agriculture and Food Security was contributedby Steve Wiggins (ODI)Morten Broberg:Professor, Faculty of Law, University ofCopenhagen. Morten Broberg has published extensively oninternational development and EU law including PolicyCoherence for Development and the regulation of EU tradewith developing countries.Rilli Lappalainen:Secretary General of Finnish NGDOplatform to the EU, member of CONCORD Europe boardwith PCD portfolio, former chair of PCD coordinationgroup.The chapter on the Danish operationalizing of PCD was contributed to byKnud Vilby, Laust Leth Gregersen (Concord Denmark), Adam Fejerskov(Concord Denmark) and Morten Emil Hansen (Concord Denmark).

Nanna Hvidt:Director of the Danish Institute forInternational Studies. Has worked on European developmentpolicies in the European Commission, at the DanishPermanent Representation to the EU and in the Ministry ofForeign Affairs.Laura Sullivan:European Policy and Campaigns Manager,Action Aid International. Coordinates ActionAid’s advocacyand campaign work in Europe.

For further information about this report: [email protected]Please go to our website for news related to Policy Coherence forDevelopment:www.concorddanmark.dk

PI Gomes:Ambassador of Guyana to the EU and Belgium. PIGomes is chairing the ACP subcommittee on sugar and wasin November 2011 elected as the chairperson of theEuropean Centre for Development Policy Management(ECDPM).

Aim of the reportThis report sends a message of urgency! Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) has for too long been articu-lated – without translating the commitments into action. Ever since the PCD agenda was introduced officially more than 20 years ago the international donor community are still experimenting and mostly involved in pilot projects. The greatest challenge is therefore to identify the right institutional model, which can realize the European PCD commitments. As stipulated in Lisbon Treaty PCD and the new Danish Development Law, PCD is a legal obligation. Getting PCD right thus matters more than ever before. With this report, Concord Denmark aspires to advance, not only the PCD agenda in Denmark, but also in Europe. The primary aim is to develop a progressive and realistic approach, which will realize Denmark’s PCD commitments. Yet, the principles and the model of operationalisation is transferable to most European contexts, and may thus be utilized to advance PCD in all EU member states. Policy Coherence for Development is a mutual obligation to assist poor countries to develop. It therefore also implies that donors move beyond the traditional donor-recipient relationship and away from a narrow focus on development aid only. We cannot demand results and question lack of progress in developing countries as long as our own policies continue to undermine Europe’s own commitment to poverty eradication. But just as important as these moral grounds, PCD is motivated by the evident need for getting value-for-money in development policy in times of rough austerity all across Europe. No matter how focused Western countries find themselves support-ing and inciting new and innovative development and poverty-eradicating policies the potential incoherencies of Western non-development policies may render all these efforts useless. As the Danish minister for Development Cooperation stated in a recent speech, “PCD is not just another ingredient of the alphabet soup, but all about mak-ing our development efforts more effective, transparent and inclusive”. The need for urgent action is illustrated by the magnitude of challenges and barriers for development stemming from incoherent European policies in three global areas, which are challenging both European policies and the poli-cies of individual EU member states: Food and nutrition security; the energy challenge with a focus on bioenergy and; Illicit financial flows. The need for more comprehensive political debates on the shortcoming and incoherence of these policies are prominent.In the report we have developed a concrete proposal for the operationalisation of PCD in a Danish context that is both realistic, transparent, and yet ambitious. Our aim is to advance the learning from other EU member states and build on existing Danish institutional mechanisms and structures, which will make PCD a systematic management tool guiding Denmark’s future policy making. We firmly believe this model will enhance Denmark’s influence on European and International policies beyond aid, and thereby also contribute substantially to the fight against global poverty. There is no valid excuse for further delaying the implementation!

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

3

Content03050913

••••••••••

172332414350

Aim of the reportExecutive Summary1. Introduction: Delivering results – How Denmark can lead theway for Policy Coherence for DevelopmentPolicy Coherence for Development in a changing world:The OECD Strategy on Development towards a broaderapproach to PCD2. Operationalizing Policy Coherence for Development:A Danish Approach3. Dressed for success or simply for the occasion?4. Policy coherence for food and nutrition security: Pointers forthe EU in 2012An ACP view on Agriculture, Food Security and Land grabbing5. Bioenergy and PCD6. Illicit financial flows

4

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

Executive SummaryWith this report, Concord Denmark aims at pushing forward, not only the Policy Coheren-ce for Development (PCD) agenda in Denmark, but in Europe. The aim of the report is todevelop a progressive and feasible approach that will realize Denmark’s PCD commitmentsand advance PCD substantially on the national agenda, but also to construct a concreteproposal for a model of operationalization that is transferable to most European nationalcontexts, and may be used to advance PCD in all EU member states. To achieve this, thereport includes six chapters. It begins by setting the scene in an introduction, a chapterpresenting the proposed Danish approach to PCD and subsequently a chapter on the ex-periences of implementing institutional PCD mechanisms in other Member States of theEuropean Union. Three chapters followingly constitute the thematic content on key issuesincluding Agriculture and Food Security, Bioenergy and Illicit Financial Flows.INtRoDuctIoNThe achievement of poverty alleviation requires more than effec-tive development assistance and focused development policies. Domestic and foreign policies are interconnected and interchanging at many levels and their scope and consequences are often difficult to trace and identify. As such, the effects of a policy in one area may easily be undermined by policies in another, both intended and unintended, and no issues can be solved in its entire isolation.

Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) addresses these issues more than anything else, by stressing how Official Development Assistance (ODA) is only one component in a complex set of poli-cies, which can promote or limit development in developing coun-tries. Policy Coherence for Development can become a decisive tool for sustainable and comprehensive development oriented coopera-tion on more equal terms between Europe and the world’s poorest countries. But this will only happen if and when proper political vi-sions and necessary institutional mechanisms are established and the right policies are implemented. All EU policies must be in support of development needs of devel-oping countries or at least not contradict the overall aim of poverty eradication. This is the obligation, which the Lisbon Treaty through article 208 on Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) has made mandatory for the European Union and its member states. At the national level Denmark is now also legally required to take account of development objectives in formulation and implantation of poli-cies across all areas affecting developing countries. The reality, however, is very different. This report from Concord Denmark points at the gap between the obligation for policy coher-ence and the very incoherent realities of current EU policies, but it is also proposing the necessary institutional mechanism which can change PCD from rhetoric to forward looking result oriented and implementable policies. After years of promises it is time to make PCD a reality. In Denmark, no systematic coordination or mechanisms of PCD have yet been established despite continuous heavy criticism from OECD (in both the 2003, 2007 and 2011 Peer Reviews of Den-mark) and repeated domestic commitments. This needs to change.

The aim of this report is thus to underline how PCD is not an ad-ministrative undertaking, but rather a political one. PCD, we argue, is not an administrative burden, but rather a responsibility for politi-cians to take positions on how to act in a complex and changeable world, where the traditional perception of development assistance and aid is challenged by externalities and incoherencies of poli-cies. Policies can naturally never achieve a level of perfection and isolation, and PCD thus becomes a case of making trade-offs and understanding how different decisions affect different issues and policy areas. We cannot demand results and question lack of progress in recipient countries when both Danish and European positions are currently hindering the potential for progress in many developing countries by maintaining and continuously formulating new policies holding policy incoherencies with negative effects for these. This report from Concord Denmark proposes a very concrete and specific model for an institutional PCD-mechanism in Denmark dealing both with Danish input to EU-policies and domestic Dan-ish policies and guaranteeing transparency and regular open political debate about the vision and objectives. It is also recommending de-velopment of research programmes in collaboration with stakehold-ers in developing countries to improve conditions for PCD screening of EU proposals, which is today both ad hoc and low scale.oPERAtIoNALIzING PcD IN A DANISH coNtExtThe report proposes a Danish institutional PCD-mechanism based in the foreign ministry and building on existing structures and pro-cesses in relation to Danish EU-policies, but involving the relevant stakeholders, including research, business and the civil society in Denmark but also partners in developing countries through a re-porting mechanism linked to Danish delegations. The mechanism is based on high-level political commitment, regular reporting and political and public debate, making it possible to assess progress or shortcomings in relation to the political priorities and the overall thematic visions for PCD.

The report proposes the following outline of the roles and responsi-bilities of different actors when operationalizing PCD in the Danish context.

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

5

It is a government decision to place the overall political responsibility for the Danish PCD-process and it is recommended that the politi-cal responsibility lie with the Minister for Development Cooperation in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Minister for Development Cooperation should be responsible for preparing and publishing the overall analytical vision that will form the baseline in monitoring and reporting on the progress of implementation of PCD mechanisms in the Danish context, and the further development and political adjustments thus remains his responsibility. The Minister for Devel-opment Cooperation should be responsible for publishing a biennial PCD progress report whose cross sector character entails that it must be discussed and approved by the government’s coordination committee before it is published.The Minister for Development Cooperation should initially be re-sponsible for a process leading to a PCD work programme with thematic focus areas. The first work programme should cover two years. After this period an annual decision on whether to change or to keep the same priorities should be made through an open consul-tative process. The work programme should reflect global challeng-es identified by the EU as well as by the new strategy for Danish De-velopment policy and it should refer to EC’s PCD Work Programme.The strengthening of PCD as an integrated part of Danish domestic and EU policy and the establishment of institutional PCD mecha-nisms needs to be based upon an overall vision for the results Den-mark wants to obtain in cooperation with the EU. Such a vision should be based on an analytical examination of the present policies within the focus areas established in the EU PCD policy.As clearly stated by the OECD, specific institutional mechanisms are a necessary element in the implementation of PCD. The European Affairs Committee of Parliament (Folketingets Europaudvalg) is a natural anchorage point in a Danish context, since the committee is specifically charged with ensuring a parliamentary debate of the ne-gotiating mandate of Danish ministers in the EU Council of Ministers.The implementation can be achieved by making PCD a mandatory section in all background notes of the European Affairs Commit-tee. In its PCD section, each background note must assess whether there are relevant international development concerns in the EU ini-tiative to which the note refersThis process is already used in relation to the “principle of subsidi-arity” and “socioeconomic effects” that are both included as man-datory sections in all background notes. As in the case of these two standard sections, a possible response to PCD relevance could be “not applicable”. VISIoNS foR tHREE kEy tHEMAtIc AREASThe report addresses three thematic issues of Danish and European politics that are of key relevance to the Policy Coherence for De-velopment agenda.

6

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

AGRIcuLtuRE AND fooD SEcuRItyPolicies to reduce the proportion of people in the world suffering from hunger and malnutrition have stalled in the last 15 years. After substantial progress between 1960s and the mid-1990s, we now see very little advancement and increased food prices have again thrown millions of people more into food insecurity. Hunger and mal-nutrition is today a reality for one billion of the world’s population.

BIoENERGyEfforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have resulted in the in-creasing use of plant biomass as energy, including for transport fuel. EU directives are encouraging this development, which involve con-siderable import of biomass and biofuels from developing countries.

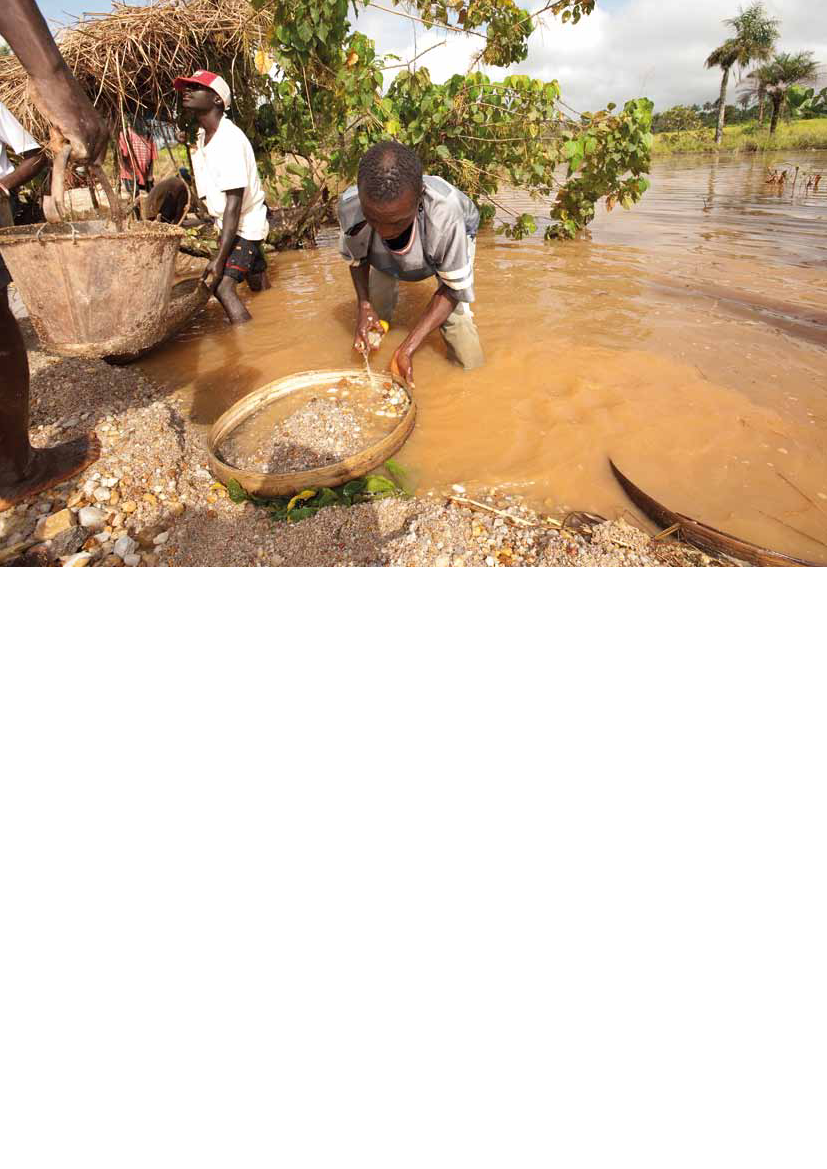

A number of new and serious challenges have made it more difficult to reach food and nutrition security in the world. The problem is not overall lack of food, but poverty combined with a new type of competition for land resources. The increasing production of biofuels and an increasing number of land deals (land grabbing) in developing countries has also lead to new and serious concern in relation to food and nutrition security. Investments in agriculture in developing countries are in principle welcome and in some countries necessary but the way land dealing take place both for growing biomass for transport fuel and as part of commercial food production can be very harmful both for poor people who may lose their land and for the environment. As a major world trader and producer of agricultural products EU has a special obligation to work for global food security. While last decade’s reforms of the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) have reduced the negative impacts on developing countries signifi-cantly, there are still evidence of cases where European subsidized exports and safety net policies have undermined the income and livelihood of smallholder producers and food security in developing countries. The impact of the CAP also involves the EU’s massive appropriation of arable land in developing countries used produc-ing feedstuffs for European production. Concord Denmark proposes the following vision and objectives in the policy area of agriculture and food security:

The basic premise behind political efforts to increase the use of bio-fuels is that it is “carbon neutral”. This premise is, however, increas-ingly being challenged by research findings. The burning of biomass does not necessarily result in reduced emission of greenhouse gas-ses, and legislation that encourages substitution of fossil fuels by bioenergy, irrespective of the biomass source, may even result in increased carbon emissions and thereby accelerate climate change and global warming.The increased cultivation of biomass for bioenergy leads to in-creased competition for land, it increases the pressure on the Earth’s land based ecosystems, and it competes with efforts to provide sufficient food for the world’s growing population. It has a negative impact on food security and it leads to growing food prices. Besides it can lead to irreversible impacts on biodiversity. Concord Denmark proposes the following vision and objectives in the policy area of bioenergy:

Bioenergy – Vision:The Danish Government envisages a European energy system basedon renewable carbon neutral energy produced in sustainable wayswith the aim of eliminating negative climate impact as a result ofenergy production and consumption. Production and consumption ofbioenergy may not in any way, directly or indirectly, have negativeimpact on food production capacities or food security in developingcountries.Political objectives:1) Guarantee bioenergy use only from additional biomass, reducinggreenhouse gas emissions without displacing other ecosystemservices2) Implement EU energy policies guaranteeing the objective offighting climate change in the promotion bioenergy.3) Guarantee that the right to food security in developing countiesare not impacted negatively and that EU and member states arenot involved in unsustainable competition for the use of arableland in developing countries to be used for bioenergy

Agriculture and Food Security – Vision:The Danish Government envisages a global agricultural system thatincentives increased production in developing countries; minimizestrade distorting polices and harness a global shift towards moresustainable and climate-smart models of production. The DanishGovernment will work to advance the Right to Food and Rights-basedFood policies.Political objectives:1) A more development friendly CAP and agricultural trading system2) A more climate-smart global agricultural and trade systemsupporting developing countries efforts to adapt and mitigatesclimate change3) Advancing rights-based food security policies at international andlocal level

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

7

ILLIcIt fINANcIAL fLowSIllicit financial flows from developing countries to the rich part of the world reach approximately 1.000 billion dollars a year or 8 to 10 times more than Official Development Assistance from the rich countries of the world to the same countries. About two third of the illicit financial flows consists of commercial tax evasion from inter-national companies.

Illicit financial flows – Vision:The Danish Government envisages a global financial system basedon transparency and a fair contribution from all types of national andinternational incomes to development purposes. The government illwork actively and including through the European Union and UN toassist developing countries in fighting commercial tax evasion andother types of illicit financial flows and strengthen taxation systemsin developing countriesPolitical objectives:1) Transparency and clear information about beneficial ownershipof all companies and account holders in all types of financialinstitutions, particularly in tax havens2) Country-by-country reporting for all multinational corporations.3) Multilateral automatic exchange of tax information betweencountries.

Illicit financial flows are made possible by the world’s financial insti-tutions and assisted by Western governments including in the Euro-pean Union. This constitutes an appalling violation of Policy Coher-ence for Development.While it is unrealistic to stop illicit financial flows completely it is sim-ple to curtail the flows very considerably. Billions of dollars can be made available for development in a much more equal partnership between richer and poorer countries if a few measures are taken.The vision and the objectives are setting the direction for EU and member state policies to fight illicit financial flows. Concord Den-mark proposes the following vision and objectives in the policy area of illicit financial flows:

8

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

1.Introduction

Delivering results – How Denmarkcan lead the way for Policycoherence for DevelopmentPoLIcy coHERENcE foR DEVELoPMENt – PoLIcy MAkINGIN A NEw GLoBAL coNtExtThe achievement of poverty alleviation requires more than effec-tive development aid. As stipulated in both in the Lisbon Treaty and the new Danish Law for Development Cooperation the develop-ment objectives must be taken into account in policy making across all areas that will affect developing countries. These legal obliga-tions reflect the realities of today’s densely interconnected world. Globalisation has now advanced to a stage where the boundaries between domestic and foreign policy are so blurred that it is no longer sensible for political decision makers to ignore the global impacts of their policy choices. Nowhere this is as evident as in the field of development cooperation where contradictive policy impact on the ground results in a waste of development money

and huge opportunity costs in the transition to a sustainable global economy. Massive outflows of illicit finance facilitated by European and Ameri-can accounting legislation dwarfs global development aid by 8-12 times. The EU’s response to milk market crisis in 2009 provides an-other grave example of how policy measures implemented in one place may displace negative impacts to other regions. As the Euro-pean Commission engaged in heavy intervention buying and reintro-duced export subsidies for dairy products resulting in a huge export surge to Sub-Saharan Africa, Camerounese dairy farmer’s eventu-ally found their livelihood being undercut when they were suddenly squeezed out of local value chains that had taken more than 10 years to build, supported by development assistance from the EU. Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results 9

Whether intended or unintended such cases are clearly unaccepta-ble, especially in times when the international community more than ever emphasises the need to deliver results in development policy. Adapting our policies in to the vastly changing global landscape is a matter of absolute urgency. The concept of Policy Coherence for Development (PCD) addresses this challenge more than any other policy instrument by stressing how Official Development Assistance (ODA) is only one component in a complex set of policies that can promote or limit development in developing countries.As global economic activity is moving East and South, development has become a multidimensional and complex issue reaching far beyond the traditional perceptions of donor-beneficiary relation-ships between rich and poor countries. For the first time in dec-ades, poorer developing countries have experienced faster growth than OECD countries in the 2000s. In far too many states however, this economic progress has not been translated into improved living standards for the poorest and most vulnerable groups. More than 70 % of 1.4 billion people that are still living in extreme poverty now reside in middle-income countries (MIC) (Overseas Develop-ment Institute 2012).Creating better conditions for the people at the very bottom of global society is not solely a moral obligation. It’s becoming increas-ingly clear that safeguarding Europe’s long-term prosperity also

depends on our ability to improve living standards of poor peo-ple in developing countries. It’s naive to think that the first can be achieved without the latter. As stressed in the latest Global Risk Report of the World Economic Forum ‘severe income disparity’ presently poses the most serious risk to for economic progress and stability in the world (World Economic Forum, 2012).To tackle the challenge of global poverty and inequality political leaders need to rethink the relationship between rich and poorer countries fundamentally. In the future, cooperation must be found-ed on a common will and mutual accountability to address the structural causes of poverty and marginalisation rather than just fo-cusing on the deployment of development aid in a donor-recipient relationship. It’s hypocritical to demand results and question lack of progress in recipient countries if we are not willing to scrutinise and recourse Danish and European policies undermining development in our partner countries. In this context PCD can become instrumental in creating a more sustainable, effective and equal cooperation between Europe and the world’s poorest countries. But this will only happen if and when the necessary political will is mobilised and proper institutional mechanisms established, and development champions like Denmark leads by example.

“the union shall take into account theobjectives of development cooperation inthe policies that it implements which arelikely to affect developing countries”Article 208 of the Lisbon treaty of the European union

”It is acknowledged, that developingcountries are not only affected bydevelopment policy efforts, but also byefforts in other policy areas”the new Danish Law for Development cooperation

10

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

With this report, we aim to demonstrate how Denmark can lay path by presenting a comprehensive political model for operationaliza-tion of PCD based on the present Danish context, of which key ele-ments can also be transferred to other EU Member States. Implementing the model will, however, require a fundamental change of attitude from the Danish Government. For almost ten years Dan-ish decision makers have failed to deliver on its commitments to the PCD agenda. Despite ambitious rhetoric from the present Govern-ment, an implementation plan is still missing and nor has any insti-tutional mechanism or strategic thinking on the subject been pre-sented. The appeals we put forward are a matter of urgency.DENMARk MuSt wALk tHE PcD tALkThe PCD agenda is not new to the Danish politicians or develop-ment community. Denmark has over the last decade, repeatedly been criticized of its lack of political will to implement institutional PCD mechanisms. OECD DAC has in its past three Peer Reviews of Denmark’s Development Assistance led this critique: In 2003, Denmark was criticized for not establishing a formal framework for PCD implementation, and in both 2007 and 2011 the criticism was repeated.

Review, the former Danish government promised to prepare an ac-tion plan to ensure that “its own domestic policies do not affect those of developing countries negatively” (OECD, 2011). The new government has strengthened the declared commitments to PCD - PCD is part of the government bill; it is part of the objectivesparagraph in the new Danish Law for Development cooperation andfeatures in the government’s Development Strategy. But still no implementation plan translating these legally binding commitments into practice has been produced. Based on the research and experiences of other countries (see chapter 2) Concord Denmark underlines that implementation must be based on a genuine political will to make PCD an integrated part of Danish domestic and EU policy. This implies a fundamental rec-ognition that PCD is an inherently political issue that must be dealt with by politicians who can be held democratically accountable rather and cannot be dealt with only by technocrats in the admin-istration (which is currently the case in most countries adopting an approach to PCD). PCD mechanisms therefore need to be an-chored in an explicit vision for the global development results Den-mark wants to obtain through development and non-aid policies, both as a national actor and in cooperation with the EU. Naturally, such visions should be based on a thorough analytical examination of the possible impacts of present and future policies, but at the

Since 2010 Denmark has made several commitments to strengthen PCD, though without any noticeable progress. In the last OECD Peer

“PcD is not just another ingredient ofthe alphabet soup, but all about makingour development efforts more effective,transparent and inclusive”christian friis Bach, Danish Minister of Developmentcooperation

“It is essential to examine theinterdependence and coherence of allpublic policies – not just developmentpolicies – to enable countries to make fulluse of the opportunities presented byinternational investment and trade, and toexpand their domestic capital markets”the fourth high Level forum on Aid Effectiveness in Busan inDecember 2011

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

11

Danish PcD check listtool-A national PcD work programmecontaining clear and tangible political visions of which results must beobtained to make Danish and EU policies coherent with developmentobjectives within certain focus areas.-A national PcD screening mechanismattached to relevant Committees of the Danish Parliament-A biennial national PcD progress reporton Work programme to the Danish Parliament published by theGovernmentoutcome- The visions both as a political platform that allow for,1. Pro-active efforts within the focus areas2. Measurement of progress and results

- Parliamentary scrutiny of the co-ordination with developmentobjectives across policy areas- Transparent monitoring and democratic accountability

same time the approach rejects the idea that indicators can be de-termined and assessed in an entirely objective manner. PCD is about political choices and priorities and as such the Gov-ernment’s policy objectives must be publicly accessible and par-liamentary scrutiny must be placed at the very heart of the PCD practice. The proposal for operationalisation of PCD in a Danish context sets out a realistic, clear and transparent Danish model for a result ori-ented institutional PCD-mechanism for working with PCD both in relation to EU and domestic Danish policies. It includes a model for its implementation that guarantees regular reporting and high-level political and public debate on results and shortcomings.Beyond the institutional focus the report also has three thematic chapters, each illustrating the magnitude of problems and some of the many serious barriers for development stemming from incoher-ent European policies and three major global challenges: Food and nutrition security; The energy challenge with a focus on bioenergy

and; Illicit financial flows. These three chapters are all written by ex-ternal experts and there opinions do thus not necessarily reflect our. In the same way, the recommendations and visions created from the chapters are done by us and do not necessarily reflect the opin-ion of the authors. It will be clear whenever this is the case.All thematic chapters also include a vision constituting Concord Denmark’s interpretation of how the issues raised in the thematic areas may be addressed in policy making. The vision also sets out overall and specific objectives that can form the basis for sensible assessment and discussions of results and shortcomings in the im-plementation of concrete policies in specific areas. The box summarises this report’s recommendations ‘check list’ of the key elements that must be included in a new Danish PCD tool box, which can translate Denmark’s legal commitments into prac-tice. The check list encompasses all of the OECD’s three building blocks for PCD: 1) Commitment 2) Policy co-ordination 3) Moni-toring. Denmark has still not yet implemented neither building block 2) or 3).

ReferencesOverseas Development Institute (2012), Sustainable and Inclusive Development in a changing World – challenge paper no 1 for DANIDA’s 50 yearsanniversaryOECD (2011), Peer Review – Denmark 2011World Economic Forum (2012), Global Risk Report

12

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

Policy Coherence for Development in a changing world:

the oEcD Strategy onDevelopment towards abroader approach to PcDEbba Dohlman, OECD

GREAtER INtERcoNNEctEDNESS cALLS foR GREAtERcoHERENcEThe global economy has been undergoing a major structural trans-formation. Developing economies, particularly emerging econo-mies, are becoming key drivers of global economic growth and play an increasingly important role in international finance, trade, inno-vation and development co-operation. Their dynamism and growth are leading to shifts in global economic governance and contribut-ing to changing the architecture of international development co-operation as well as the nature of development financing.

between the “North” and the “South”, and allow for cross fertilisa-tion between different experiences and diverse development mod-els. Development is multidimensional in nature. To understand its pros-pects requires approaches that cut across multiple disciplines, that tap into the diverse experiences, knowledge and different perspec-tives from countries, international organisations, policy communi-ties and key stakeholders, and that take into account the need for PCD at the national, regional and global level.tHE oEcD’S RoLE IN PRoMotING PcDThe OECD has worked to promote PCD for its members since the early 1990s, and the approach has evolved over time. An OECD Ministerial mandate in 2002 focused PCD work on two main di-mensions 1) avoiding impacts that adversely affect the develop-ment prospects of developing countries, and 2) exploiting the po-tential of positive synergies across different policy areas, such as trade, investment, agriculture, health, education, the environment and development co-operation.2 The OECD work focused mainly on institutional, sectoral, and country-specific levels. It contributed to raise awareness and foster analysis on development impacts of members’ policies. It also developed a framework for assessing DAC members’ progress towards PCD. This is conceptualised as three-phase cycle, with each phase supported by a “building block”: (i)political commitment and policy statements; (ii) policy coordination mechanisms; and (iii) systems for monitoring, analysis and report-ing.3 This framework has been a key element in the guidance for carrying out DAC peer reviews since 2002. At this time, the DAC started systematically including a chapter on “Beyond aid” which looks at the DAC members’ political commitment and how their government organisations work to promote PCD, including their capacity to analyse the potential impact of policies on development and monitoring results.

With the structural realignment in the global economy, the geog-raphy and structure of poverty are also changing. A growing pro-portion of the world’s poor is living, and will live, in middle-income countries and urban areas rather than in low-income countries and rural areas. As Official Development Assistance (ODA) becomes a shrinking portion of the overall budget for poverty reduction pro-grammes, sound institutions, good policies and improved policy-making, play a key role in fostering sustainable economic growth that is inclusive of the poor. ODA remains critical, particularly for the Least Developed Coun-tries as a key source of development financing, and can play a catalytic role. At the same time, there is a growing recognition of the crucial role of policy coherence for development (PCD). Fos-tering mutually supportive policies across a wide range of eco-nomic, social and environmental issues can unleash the develop-ment potential of countries, and help them transition away from aid dependence. As highlighted in Busan it is essential to examine the interdependence and coherence of all public policies, not just development policies.1In an increasingly interconnected world economy, challenges have become global. Economic shocks can reverberate quickly, and ex-ternalities such as macro-economic instability, social and economic inequalities, and conflict can have large and wide ranging spillover effects worldwide. At the same time development challenges have implications for all. Collective and coordinated action to address these challenges therefore needs to transcend the old distinction

The OECD Ministerial Declarationadopted in 2008 further strengthened the dual-focus of OECD’s PCD work. In the Decla-ration, Ministers reaffirmed their strong commitment to PCD and resolved to continue efforts to ensure that development concerns

1) “Busan Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation”[http://www.aideffectiveness.org/busanhlf4/images/stories/hlf4/OUTCOME_DOCUMENT_-_FINAL_EN.pdf]2) “OECD Action for a Shared Development Agenda” From the OECD Council at Ministerial Level, Final Communiqué, 16 May 2002.[http://www.oecd.org/document/46/0,2340,en_2649_33721_2088942_1_1_1_1,00.html]3) OECD (2009): Building Blocks for Policy Coherence for Development, Paris.

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

13

are taken into account across relevant policies. They requested the OECD to help enhance understanding of the development dimen-sion of policies and their impact on poverty reduction. A new ele-ment was to strengthen dialogue with partner countries in sharing experiences on the effects of OECD members’ policies on develop-ment and to consider the increasing relevance of PCD in develop-ing countries’ policies. They also called for better international co-ordination to help ensure that benefits of globalisation are broadly shared.4 In 2010, an OECDCouncil Recommendationcalled on members to take further measures to strengthen PCD. It identified institutional practices and lessons learned, drawing on DAC peer reviews and on work by the OECD Public Governance Committee, to foster “whole of government” approaches to policy-making and help to better integrate consideration of development issues in designing and im-plementing national policies.5At the level of the Organisation, the OECD established in 2007 a dedicated unit in the Office of the Secretary General to promote

PCD, consistent with its own good institutional practice recommen-dations. Since then, Committees and Directorates have been en-couraged to identify inter-linkages across policy areas to strengthen the integration of the development dimension in their programmes of work, enhance synergies and develop joint projects. To facilitate the sharing of good practices and evidence-based analysis on PCD, the OECD also set up a Network of National Focal Points for PCD in 2007 and launched in November 2011 a web-based InternationalPlatform on Policy Coherence for Development.6 In 2012, at the OECD’s 50th Anniversary Ministerial Council Meet-ing (MCM), members made an historic decision to launch an OECDStrategy on Development. They endorsed a strategic Frameworkwhich provides the Organisation with the basis to broaden its ap-proach to development, drawing more effectively on its multidis-ciplinary expertise and longstanding experience in development and development co-operation, and strengthening its partnerships and mechanisms for knowledge sharing.7 The Framework outlines the key elements of a comprehensive approach to development, in which PCD is a core objective. A new element is the emphasis in fos-

4) C/MIN(2008)2/FINAL, 4 June 2008. “OECD Ministerial Declaration on Policy Coherence for Development”[http://acts.oecd.org/Instruments/ShowInstrumentView.aspx?InstrumentID=138&InstrumentPID=134&Lang=en&Book=False].5) C(2010)41, 29 April 2012. “OECD Council Recommendation on Good Institutional Practices for PCD”[http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/6/54/46159783.pdf]6) Visit: https://community.oecd.org/community/pcd7) See: C/MIN(2011)8, “Framework for an OECD Strategy on Development”, endorsed at the OECD 2011 Ministerial Council Meeting[http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/8/17/48106820.pdf].

14

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

tering PCD at different complementary levels: with members, within the OECD itself, as well as with partners countries and globally. towARDS A BRoADER APPRoAcH to PcDDespite the political will expressed by OECD members in 2008 as well as the efforts made by most DAC members to put in place the necessary institutional mechanisms, limited progress has been made in delivering better policy coherence for development. Ex-perience with peer reviews on instititutional practices and mecha-nisms for PCD has shown that the three building blocks for PCD, are necessary to raise awareness and build efficient decision-making, but not sufficient to translate into greater PCD policy making. In addition, DAC peer reviews do not go into detailed thematic and sectoral analysis or impact assessments. In fact, most PCD com-mentators point out that the biggest challenges to achieving pro-gress is the lack of robust methodologies and indicators to measure progress and as well as of specific evidence-based impact analysis adapted to country contexts.

• Consider PCD relevance for developing countries.PCD has had a strong donor focus. Dialogue on issues related to PCD has been carried out mainly among donors and focused on the incoher-ences between aid and non-aid policies. This will continue to be important to ensure mutual accountability, but PCD also has a domestic dimension and applies to both advanced and devel-oping economies. Understanding the policy inter-linkages and trade-offs can help inform decision-making to prevent con-tradictory policies and strengthen development impact. For in-stance, trade between developing countries themselves – what we call south-south trade – depending on the policy choices could be one of the main engines for growth over the coming decade. OECD estimates suggest that were southern countries to reduce their tariffs on southern trade to the levels applied between northern countries, they would secure a welfare gain of USD 59 billion.8• Take into account the global dimension of PCD.PCD in the new global context is also about creating an enabling environment for mutually supportive policies to unleash the development poten-tial of countries. As stated in the Monterrey Consensus, national efforts (policies) need to be supported by an enabling interna-tional economic environment to send the right policy and mar-ket signals, create confidence, and facilitate cooperation and ex-change among sectors and governments. From this perspective, PCD can facilitate the design of collective responses to global development challenges, and build common ground on global public policies and the provision of global public goods.One example where such a multidimensional and cross-cutting ap-proach to PCD is necessary is global food security. This is an issue which requires action by OECD members, by developing countries and at the global level. The challenges include amongst others: im-proving agriculture productivity as well as research and innovation systems; reducing waste; reconciling increased agricultural produc-tivity with other potentially competing objectives and constraints, such as bioenergy, water scarcity, climate change; facilitating and increasing trade; and creating enabling environments for invest-ment by removing barriers and incoherent policies. PCD can serve as a tool to address these interlinked factors. tHE oEcD StRAtEGy oN DEVELoPMENt: EMBARkING oN ABRoAD EffoRt to ENHANcE PcDThe OECD Strategy on Developmentseeks to adapt OECD ap-proaches to a rapidly changing global context. Three elements are considered essential to address development in the current con-text: 1) more effective collective action that involves key actors and stakeholders, through inclusive policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and mutual learning, as well as stronger partnerships; 2)more comprehensive approaches to address the multidimensional-

Against this background there is a need for updating and broaden-ing the PCD approaches, adapting our instruments, and responding more effectively to the increasingly complex development chal-lenges. This means not only deepening our evidence-based analysis and strengthening our tools for members, but looking also at the global and cross-sectoral dimensions of PCD, as well as the rele-vance of PCD issues for developing countries. PCD Going forward, key actions to improve the design and implementation of more co-herent policies could include:• uild more systematic approaches to evidence-based analysesBwith strong involvement of developing countries.Feedback from developing countries on the impact of policies on development is fundamental to generate the necessary evidence to inform policy and convince decision makers to act. This dialogue is particularly needed given the heterogeneity of developing countries and the fact that policies might affect each country differently. Without systematic dialogue and feedback, country-specific impacts are difficult to determine.• Shift the focus away from a single-sector to multidimensionaland cross-sectoral approaches.Efforts to improve understand-ing of incoherence and to promote development-friendly policies have been carried out on a sector-by-sector basis, such as trade, agriculture, investment environment, technology, migration, amongst others, but without giving due attention to the inter-sectoral inter-linkages and the multidimensionality of develop-ment challenges. There is a need to reduce the sectoralisation and to look in a comprehensive manner at a range of inter-related factors and relevant areas for designing more coherent policy so-lutions.

8) OECD (2010): Perspectives on global development 2010: shifting wealth, Paris.

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

15

ity of development; and 3) greater emphasis on policy coherence for development. The OECDStrategy on Development will be open OECD’s policy dialogue to a wider range of countries on the basis of mutual learning among peers, strengthen its support for members and partners who aspire to better policies for better lives, and con-tribute more effectively to development process and global devel-opment architecture.In line with this comprehensive approach, the OECD will scale up its work on PCD to:• upport more effectively its members, by fostering collabora-Stion with other partner institutions to develop PCD indicators, monitor progress and assess the impact of diverse policies on development in a more systematic manner. • Ensure that OECD’s policy advice is coherent and consistent with development, by mainstreaming the development dimension throughout Directorates and Committees, re-focusing analyti-cal work to take into account the impact of specific policies on development outcomes, identifying particular areas of policy in-coherence as well as synergies; and reinforcing the existing insti-tutional mechanisms for PCD within the Organisation. • trengthen the mechanisms to promote greater opportunities Sfor dialogue and knowledge sharing with developing countries and key stakeholders on the effects of policies on development and to share experiences and good practices on PCD; and build strong evidence on the cost of incoherent policies as well as on the benefits of more coherent policies.• Apply a PCD perspective to global public goods and “bads” as well as key global issues which need to be addressed in a comprehen-sive manner, such as global food security, illicit financial flows and green growth.

16

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

2.Operationalizing Policy Coherence for Development:

A Danish ApproachINtRoDuctIoNConcord Denmark will in the following outline how the principle of Policy Coherence for Development can be operationalized in a Dan-ish context and propose concrete actions that must be adopted by the Danish government in order to ensure a successful implementa-tion of PCD. After having summarized Denmark’s commitments to Policy Coherence for Development, we will identify existing insti-tutional mechanisms and discuss how the Danish government can substantiate the Danish PCD endeavors within both existing and new institutional frameworks, and outline the roles and responsi-bilities of different actors in the operationalization.

“Denmark needs to strengthen policy coordination mechanisms andsystems for monitoring, analyzing and reporting on the impacts ofboth Danish and EU policies on development in partner countries”(OECD, 2011).Since 2010 Denmark has made several commitments to strengthen PCD, though without any noticeable progress. In the last OECD Peer Review, the Danish government promised to prepare an action plan to ensure that “its own domestic policies do not affect those of de-veloping countries negatively” (OECD, 2011). The government also promised to “strengthen the coherence between policy areas and instruments for the benefit of development” in the 2010 Strategy for Denmark’s Development policy, and the new government also declared its commitment to PCD in the government bill, stating that “The Government will work to ensure better coherence between EUpolicies within all the many sectors affecting developing countries”.In spite of the international criticism, Denmark has not yet drafted or adopted a plan of action for the operationalization of PCD.tHE ExIStING MEcHANISM foR PREPARING DANISH EuPoSItIoNSThe European Affairs Committee of the Danish Parliament (Folket-inget) is the parliamentary committee approving the Danish posi-tion and mandate in relation to EU-policies, and the institutional structure is the following: The first institutional level for preparing the Danish position on specific policy initiatives from the European Commission is called the EU Special Committees (Specialudvalg). A number of EU Special Committees deal with different aspects of EU policies. The committees are convened by the ministry with primary responsibility for a given policy area and consist of civil servants and often include representatives from interest groups such as la-

The aim is not only to develop a progressive and feasible approach that will realize Denmark’s PCD commitments and advance PCD substantially on the national agenda, but also to construct a con-crete proposal for a model of operationalization that is transferable to most European national contexts, and may be utilized to advance PCD in EU member states. DANISH coMMItMENtS to PcDThe Policy Coherence for Development agenda is not new. Denmark has over the last decade repeatedly been criticized for its lack of political commitment to implement institutional PCD mechanisms. OECD DAC has led this heavy critique in its past three Peer Re-views of Denmark’s Development Assistance. In 2003 Denmark was criticized for not establishing a formal framework for PCD im-plementation and Danida was criticized for lack of leadership among Danish institutions in promoting PCD in decision-making processes. In both 2007 and 2011 the criticism was repeated; “There is noformal framework within which the MFA can take the lead in pro-moting policy coherence for development with other ministries. Thisremains as much a challenge as it was in 2003”(OECD, 2007); and

Political commitment and policy statements– Danish Law on Development Cooperation– Danish Development Strategy– Danish government platform

Systems for monitoring, analysis and reporting– Biennial PCD progress reports– open consultative process in revision of PCDwork programme

Policy co-ordination mechanisms– PCD work programme with specific focus area– screening of existing and proposed policies– include PCD assessment in all background notes– see implementation model

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

17

18

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

bor unions, employer associations, environmental organizations and think tanks. The legislative basis for developing Denmark’s position in a given area is in the form of official background notes (samle-notater), which represent an important channel for influencing the official position. The prepared position then subsequently moves through a ministerial chain of command until it ends up as recom-mendations to the Europe Committee in the Parliament.outLINE foR A DANISH PcD INStItutIoNAL MEcHANISMThe operationalization of PCD needs to be strongly anchored in government. The political commitment and policy implementation needs to emerge from the highest possible level, as PCD in principle encompasses all policy areas and because the responsible admin-istrative mechanisms need to benefit from the greatest possible political support to achieve the goal of making development policy objectives cut across government as an overarching area of focus.

level a decision to only focus on a handful of issues will be a dilution of the PCD efforts rather than a concretization.The institutional mechanism aims at involving not just the relevant Danish PCD-stakeholders but also to include channels and methods for people in developing countries to be heard when they are af-fected negatively in their rights to development by incoherencies in EU policies.The following sections outline the roles and responsibilities of dif-ferent actors when operationalizing PCD in the Danish context, in-cluding concrete proposals for institutional mechanisms and instru-ments of systematic coordination.tHE GoVERNMENt LEVELIt is a government decision to place the overall political responsibility for the Danish PCD-process and it is recommended that the politi-cal responsibility lie with the Minister for Development Cooperation in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Minister for Development Cooperation should be responsible for preparing and publishing the overall analytical vision that will form the baseline in monitoring and reporting on the progress of implementation of PCD mechanisms in the Danish context, and the further development and political adjustments thus remains his responsibility. The Minister for Devel-opment Cooperation should be responsible for publishing a biennial PCD progress report to the Parliament whose cross sector charac-ter entails that it must be discussed and approved by the govern-ment’s coordination committee before it is published.

The outline is developed on the basis of the principles described in OECD’s building Blocks for Policy Coherence for development (2009): The Policy Coherence cycle.The Danish PCD effort should be two-sided and have both a national and a European focus. The national focus should be anchored at min-isterial level through a PCD mechanism that simultaneously screens proposed policies for their potential negative impact on developing countries, through participation in relevant committees. Through this process, Denmark would be able to ensure that its policies are not in conflict with the objectives of development cooperation.At the European level, Denmark’s efforts should help ensure that the different policy areas of the EU are not in conflict with the ob-jectives of European development cooperation, by advancing Dan-ish EU positions that are in line with the national efforts of elimi-nating incoherencies influencing negatively on developing countries.The mechanisms need to build upon existing structures for pre-paring positions on both domestic and international policies, but in order to maintain significant influence and impact, PCD needs to be established as a main thematic task that benefits from a clear mandate – the pursuit needs to move from a latent part of policy-making to a clear outspoken objective in practice.When pursuing PCD in a European context it must be a priority to identify thematic focus areas, in which Denmark is considered to have an advantage in relation to political leverage. The present problems with pursuing an effective PCD agenda at the EU level show the need for more active efforts of member state govern-ments to strengthen and influence EU policies and a national Danish mechanism based on thematic priorities will benefit this process. In the national pursuit specific thematic areas of focus are less im-portant and the screening of proposed policies in practice should aim at eliminating incoherencies in all policy areas. At the national

The Minister for Development Cooperation should initially be re-sponsible for a process leading to a PCD work programme with thematic focus areas. The first work programme should cover two years. After this period an annual decision on whether to change or to keep the same priorities should be made through an open consultative process. The work programme should reflect global challenges identified by the EU as well as by the new strategy for Danish Development policy and it should refer to EC’s PCD Work Programme.The strengthening of PCD as an integrated part of Danish domestic and EU policy and the establishment of institutional PCD mecha-nisms needs to be based upon an overall vision for the results Den-mark wants to obtain in cooperation with the EU. Such a vision should be based on an analytical examination of the present policies within the focus areas established in the EU PCD policy.PcD VISIoNS AS PoLItIcAL BENcHMARkEver since the PCD agenda have entered official institutions, meth-odological discussions have centered on the challenge of how to measure the coherence of policies with development objectives. Presently, a consensus on the need to move towards more evi-dence-based PCD and to evaluate progress on the basis of indi-cators is emerging. The implicit assumption here seems to be that

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

19

evidence and indicators can be determined and assessed in an ob-jective manner. However, this approach disregards the very political nature of the PCD principle. Rather than trying to define technical indicators, the biennial Work Programme should set out clear political visions of how Denmark want to see policies in different areas move in a more development friendly direction. Such visions should also include overall objectives that can serve as PCD benchmarks of the government’s policies and EU positions in relevant political processes that are taking place within the scope of biennial work programmes. The political visions and their policy implications may naturally be challenged in discussions on concrete political decision. E.g. the op-position or other stakeholders may voice their disagreements in public or parliamentary debates and even succeed in overturning the government’s position. Yet, this is part of the political PCD game and legitimate democratic scrutiny of any government. Concrete examples on PCD visions can be found on page 40, 49 and 54. tHE ADMINIStRAtIVE LEVELA specific PCD mechanism should be established within the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, with the following main tasks;

Second, all background notes to the European Committee in Parlia-ment shall include a compulsory section establishing whether a policy or legislative proposal have impacts on development objectives – a PCD-assessment. This is already common practice in the Netherlands. The selection criteria, for which EU initiatives are relevant for such as-sessments, should be the European Commission own PCD-screening of its annual work programme used for inter-service consultations. Assessments may be based on inputs from external stakeholders with relevant expertise in line with the already existing hearing procedures of the Specialudvalg of the European Committee.Third, the PCD-mechanism should include a mechanism for receiv-ing, assessing and addressing reports from partners in developing countries on incoherencies in relation to the impact of Danish and EU policies and ultimately the economic, social and political devel-opment influenced by these policies. PCD is an essential part of the rights based policy for development, and it is important to develop the policy in dialogue with partners and civil society organizations. It will involve the active participation of Danish embassies to de-velop and promote such a reporting system, which will also include unintended technical and bureaucratic barriers hindering develop-ment. Forth, Danish PCD-assessments are made available for the PCD-process in the EU, including for the EU Commission and the Euro-pean Parliament, and a system is established for exchange of les-sons learned among likeminded EU member states trying to move forward the PCD-agenda.It is recommended that the administrative responsibility for a PCD-mechanism be placed in the management group of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.tHE StAkEHoLDER LEVELExternal stakeholders should be considered a resource base and their insight and knowledge should be utilized and taken into ac-count in both the preparation of the initial Danish PCD work pro-gramme and the subsequent annual consultative processes on the revision of this. Their access to the EU special committee should furthermore be enhanced and their role formally institutionalized.

Screen existing and proposed policies for their potential negative effects on developing countries and Denmark’s development assis-tance, 2) support committees across ministries in reporting on the potential negative effects of proposed policies, and more specifi-cally support the EU Special committee in supplementing all back-ground notes with a section on PCD and the potential negative ef-fects of relevant included policies, 3) report biennially to Parliament on the Danish PCD progress.Aside from these general responsibilities, several specific tasks should be of importance. First, Policy Coherence for Development should be an annual is-sue for discussion at negotiations and meetings with partners in countries receiving Danish development assistance. Such meetings and discussions should both guide Danish priority setting and PCD-assessments and improve the possibilities for Southern partners to influence policy coherence in their relations and negotiations with EU. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for preparing this process and may commission studies that serve as input or look at specific issues emerging from the process.Recurrent discussions of focus areas should also be made in rela-tion to the biannual strategic discussion at the beginning of each changing EU Presidency, with the relevant work programmes of the European Commission and the EU Presidency as point of de-parture.

The PCD-assessment included in background notes will be based on the inter-ministerial work of the EU special committees, but the work shall include the involvement of relevant stakeholders from civil society, the business community and research institutions. When necessary the PCD-mechanism can also order external input as part of the assessment.Partners in developing countries are similarly invited to submit ex-amples of lack of coherence for development both in policies and in bureaucratic and technical procedures of relevance for EU and/or Denmark. Partners should be invited to report through the Danish embassies or through civil society organizations.

20

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

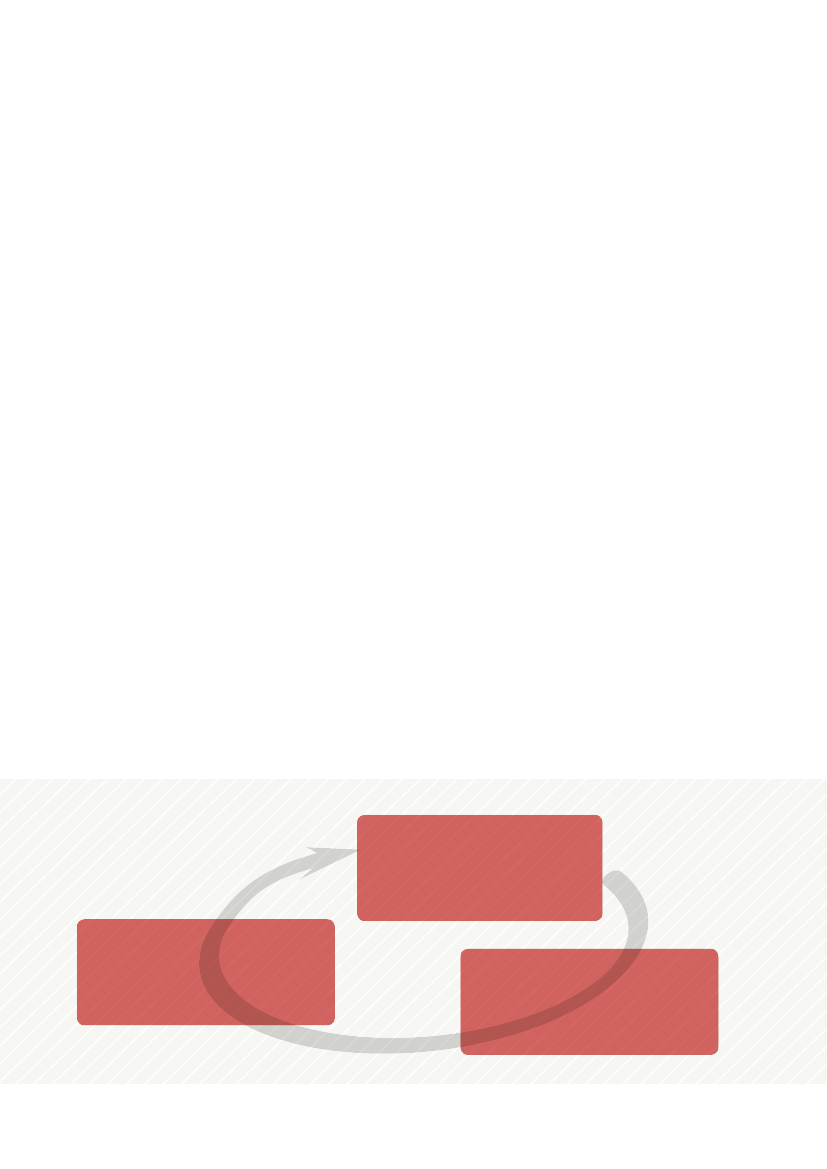

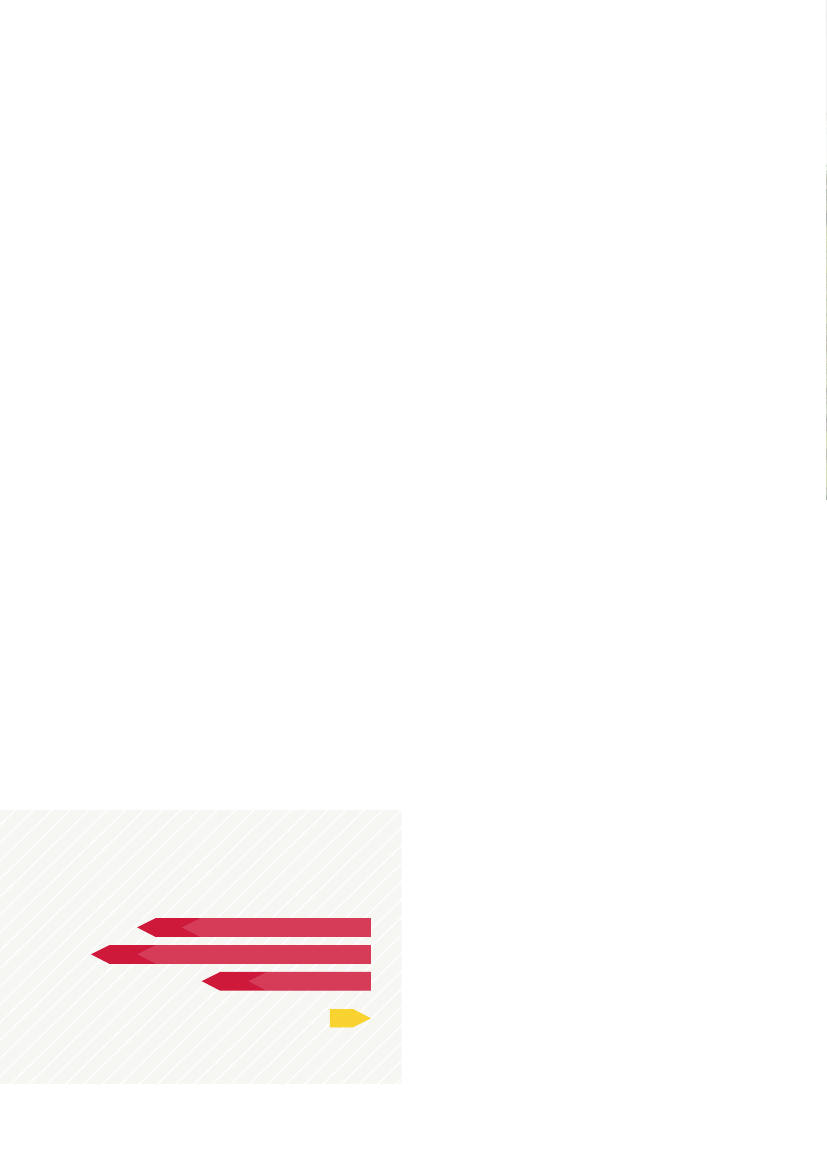

Model for implementation of a Danish Institutional PCD-mechanismAs clearly stated by the OECD, specific institutional mechanisms is anecessary element in the implementation of PCD. The European AffairsCommittee of Parliament (Folketingets Europaudvalg) is a naturalanchorage point in a Danish context, since the committee is specificallycharged with ensuring a parliamentary debate of the negotiating mandateof Danish ministers in the EU Council of Ministers.The implementation can be achieved by making PCD a mandatory sectionin all background notes of the European Affairs Committee. In its PCDsection, each background note must assess whether there are relevantdevelopment concerns in the EU initiative to which the note refers. ThePCD section will also implicitly address other relevant ParliamentaryCommittees (e.g. Foreign Affairs, Agriculture or Environment) that receivethe background notes in parallel with the European Affairs Committee.The procedure thus encourages PCD co-ordination between the differentCommittees of the Danish Parliament.A similar process is already used in relation to issues of “principle ofsubsidiarity” and “socioeconomic consequences” that are both included asmandatory sections in all background notes. As in the case of these twostandard sections, a possible response to PCD relevance could be “notapplicable”.

Screening bythe commissionActoRDG DevCo

AdministrativeplanningEU Coordination Unit– EU developmentdepartment in the MFA- NGDOsPlanning meeting

Eu Specialcommittee processEU Special Committees– NGDOs – externalexpertise

European AffairscommitteeMinister – EuropeanAffairs Committee

PRocESS

PCD screening of theCommission’s workprogramme

Presentation – writteninput

Meeting in the EuropeanAffairs Committee/and other relevantCommittees involved inthe particular process.Negotiation mandate ofthe Danish minister

outcoME

PCD input to theCommission’s inter-service consultations

Decision on PCD inputfor EU Special Committeedebate

PCD section in allbackground notes

1. Screening by the Eucommission:The PCD unit of DG DevComakes a screening of theCommission’s annual workprogramme and chosesinitiatives where PCD input willbe provided during the inter-service consultations in theCommission.– the screening of thecommission providesthe basis of the Danishplanning

2. Danish administrativeplanning:EU Coordination Unit,responsible of coordinatingthe EU input of the ministriesand the special committees,meet annually with the EUdevelopment departmentin the MFA and the variousorganisations and decide onwhich EU initiatives to offerPCD input.– the Danish planningmeetings provide the basisfor ensuring PcD inputto the special committeeprocessing of the chosenEu initiatives (input can beeither written or throughaudience).

3. Eu Special committeeprocess:Civil society organisationsprovide input – written orthrough audience depending onthe procedure of the individualprocess. It can be decidedto also invite other externalexpertise from researchinstitutions such as DIIS orequivalent as opponents.– the external inputprovides the basis ofthe PcD section in thebackground note on thespecific initiative.

4. Process in the EuropeanAffairs committeeAll PCD sections in backgroundnotes are included as part ofthe basis of the debate of theEuropean Affairs Committee onspecific EU initiatives.– the minister can, afterdebate in the EuropeanAffairs committee, beassigned a regard for PcDas part of the negotiationmandate in the Eu councilof Ministers.

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

21

Danish development NGOs are normally only involved in the work of the EU Special Committee on development, not in other EU special committees of relevance for PCD. As a consequence of the PCD-policy Danish development NGO’s should become part of more than the EU Special Committee on development. This would make them able to promote a PCD perspective in a wider range of forums.Concord Denmark has been invited to participate in Special Com-mittees on Development, Agriculture and Financial regulation. But this is an informal participation, which has not yet been formalized institutionally.Concord Denmark as a network and other relevant development NGO’s should be given access to the special committees in all leg-islation processes. What legislation is considered relevant should be based on Danish thematic focus areas and be decided on basis of the European Commission’s own screening of the EU annual work programme carried out by DG DevCO.tHE PARLIAMENtARy LEVELThe Minister for Development Cooperation presents the annual re-port on the PCD process to the European Committee and the For-eign Committee in Parliament. Parliament should then subsequently discuss the report in a parliamentarian debate. The report is made public and relevant stakeholders are invited to submit comments to the findings and conclusions.

tHE NEw DANISH DEVELoPMENt StRAtEGyDesigning an ambitious Danish institutional set-up for Policy Coher-ence for Development must be a key priority in the preparation of Denmark’s new Development Policy.

With growing demands of value-for-money and results from the recipient side of development assistance, PCD should be incor-porated in the new strategy as a responsibility that we must take on ourselves to uphold the high expectations of effectiveness in development cooperation. We cannot demands results and ques-tion lack of progress in recipient countries when both Danish and European positions are currently hindering the potential for pro-gress in many developing countries by maintaining and continuously formulating new policies holding policy incoherencies with negative effects for these.PCD should not only be written into the new Development Policy as a vague crosscutting issue. Rather it should be in the centre of the new Development Policy, signaling clear-cut political will and ambi-tion of integrating PCD into the heart of the government.Aside from the institutional mechanisms proposed in this chapter, the new Development Policy should determine and prepare specific benchmarks and baselines on the progress of implementing PCD in a Danish context, allowing for a transparent and accountable pro-cess of monitoring the efforts.

References:OECD, 2003 “Denmark – DAC Peer Review” OECD, ParisOECD, 2007 “Denmark – DAC Peer Review” OECD, ParisOECD, 2011 “Denmark – DAC Peer Review” OECD, Paris

22

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

3.

Dressed for success or simplyfor the occasion?Assessing institutional mechanisms to re-present interests of low-income countriesin European policy processesBy Niels Keijzer, ECDPM

1) EuRoPEAN coMMItMENtS to PcD: fRoM MAAStRIcHtto BuSAN?On the 1st of December 2011, a wide variety of development stakeholders gathered in Busan, Republic of Korea, to endorse a new partnership for effective development cooperation. While poverty and inequality were confirmed as remaining at the core of the chal-lenge of global development, the outcome document adopted at this fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness acknowledges

that “(…)it is essential to examine the interdependence and coher-ence of all public policies – not just development policies – to enablecountries to make full use of the opportunities presented by inter-national investment and trade, and to expand their domestic capitalmarkets.” 1Building on existing international declarations2, the out-come document thus clearly expressed that development aid will never bring development on its own, and that other policies should make positive contributions to global development. Although coun-tries with an increasing influence on global development – including China, Brazil and India – only agreed to implement the agreements made in Busan on a voluntary basis, the outcome of the meeting was welcomed and considered significant by many stakeholders. Commitments to improving the coherence of public policies to-wards development objectives are nothing new for the European Union and join an impressive queue of existing statements on what

1) The Busan Outcome Document is available here: www.aideffectiveness.org/busanhlf4/images/stories/hlf4/OUTCOME_DOCUMENT_-_FINAL_EN.pdf2) E.g. the UN Millennium Declaration, the 2002 Monterrey Consensus and the 2010 UN MDG Review Outcome Document.

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

23

has become known as Policy Coherence for Development (PCD). Re-using language that had been in the EU Treaties since 1992, the Treaty for European Union (or ‘Lisbon Treaty’), which entered into force in December 2009, states that the Union ‘(…)shall take ac-count of the objectives of development cooperation in the policiesthat it implements which are likely to affect developing countries(Art. 208).’ Of these development objectives, the primary objec-tive is defined by the same article as ‘the reduction and, in the long term, the eradication of poverty.’3 The 2005 European Consensus for Development emphasises that poverty is a multidimensional phenomenon, and that its reduction depends on giving equal at-tention to investing in people, the protection of natural resources to secure rural livelihoods, and investing in wealth creation.Given that the term ‘policy’ can be defined in many ways, it is im-portant to stress that the process of promoting Policy Coherence for Development should cover the full sphere of influence of the EU: from highly politicised policy reform processes with large financial implications (e.g. the review of the Common Agricultural Policies) to rather technical policy implementation issues (e.g. levels of toxins in imported products and acceptable sizes of vegetables) to the en-forcement or absence of EU policies (e.g. how to make sure that all European fishing vessels outside its borders follow EU regulations?). This wide field of work means that promoting PCD is highly chal-lenging in a political, technical and institutional sense, but also that “wherethere is a will, there is a way”. In the past two decades, various studies have emphasised the need to establish institutional ‘mechanisms’ that have to help govern-ments deliver on these commitments. In April 2006, the European Council of Ministers adopted a political statement in which it invited ‘(…)the Commission and the Member States to provide for ade-quate mechanisms and instruments within their respective spheresof competence to ensure PCD as appropriate’ (Mackie et al 2007). Such mechanisms can help to clarify the political level of ambition and direction for the EU’s contribution to global development (ex-plicit policy statements), help to facilitate the exchange of views and adoption of coordinated positions inside government (institu-tional coordination) and provide research or monitor the degree to

which the EU as a whole or its individual Member States contribute to development (knowledge input and assessment). The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has played a particularly important role in informing Eu-ropean and international discussions on PCD. The OECD’s work on PCD was mandated at the 2002 OECD Ministerial Council Meeting as part of the ‘OECD Action for a Shared Development Agenda’. OECD Ministers renewed their commitment to PCD in June 2008 by issuing a Ministerial Declaration on PCD4 that encouraged mem-bers to continue best practices and guidance on PCD promotion and improve methods of assessment of results achieved. Since 2000, all peer-reviews of the members of the OECD’s Development As-sistance Committees include a chapter on PCD. This chapter looks at what progress has been made in terms of promoting policy state-ments, institutional mechanisms, what efforts are made in the area of assessments – besides pointing to particular achievements or challenges in relation to specific policy areas. 5The OECD secretariat is currently preparing a strategy on development that describes how OECD members can “(…)contribute to a future in which nocountry will have to be dependent on development assistance” across its full range of policies (OECD 2011b).This chapter will look at what progress has been made by different EU member states in terms of putting in place mechanisms to pro-mote PCD. It has been structured as follows:• ection 2 presents some basic concepts, a brief theoretical Sbackground and puts forward some ideas as to what mechanisms might be effective in different country contexts• ection 3 looks at past discussions in the EU and OECD about Smechanisms, and discusses to what extent progress in creating PCD mechanisms have contributed to PCD. • ection 4 looks at a limited number of cases of specific mecha-Snisms in different contexts• ection 5 puts forward a selection of conclusions and recom-Smendations that mainly point to a need to improve assessment and awareness of how high-income country policies affect the lives of people in low-income countries.

3) In Global Policy statements, similar commitments are increasingly found, most notably in relation to Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 8 thatconcerns giving shape to a global partnership for development. The most recent high-level review of the MDGs included the following specificparagraph on PCD, as well as the additional references to particular policy areas that should be made more coherent: “We call for increased efforts at alllevels to enhance policy coherence for development. We affirm that achievement of the Millennium Development Goals requires mutually supportiveand integrated policies across a wide range of economic, social and environmental issues for sustainable development. We call on all countries toformulate and implement policies consistent with the objectives of sustained, inclusive and equitable economic growth, poverty eradication andsustainable development” (UN 2010: 41).4) http://acts.oecd.org/Public/Info.aspx?lang=en&infoRef=C/MIN(2008)2/FINAL5) According to the DAC website, Each DAC member country is peer reviewed roughly every four years with two main by examiners from two DACmember states. The process typically takes around six months to complete and culminates with the publication of the findings. Eighteen months aftereach review, the DAC Chair visits the reviewed country to check its progress in implementing its peers’ recommendations. All reviews (Denmark wasreviewed in 2011) can be accessed here: www.oecd.org/document/41/0,3746,en_2649_34603_46582825_1_1_1_1,00.html

24

Concord Danmark ¶ Delivering results

Politicalcontext

i. Policy statementsof intent

NSAPressures