FACT SHEET

Remote Electronic Monitoring: How Cameras on EU

Vessels Can Help to End Overfishing

To effectively manage our oceans and end overfishing, regulators must be able to collect high-

quality data on the health of fish populations and ensure compliance with regulations. Managers

have historically relied on a variety of methods to collect this data (e.g. logbooks, human observers,

dockside monitoring, at-sea patrols), but these tools cover a limited proportion of fishing activities,

are subject to bias or misreporting, and can be expensive and imprecise. As a result, most fishery

managers lack the basic science information that they need to get the rules of the game right, and

equally do not have the right compliance information to ensure that fishers play by those rules. To

address this, the revised EU Fisheries Control Regulation must mandate the introduction of Remote

Electronic Monitoring with cameras onboard all vessels over twelve metres in length, alongside an

additional percentage of small-scale vessels that are at a high risk of breaching the rules of the

Common Fisheries Policy (CFP).

Remote Electronic Monitoring – What it is, and why it matters.

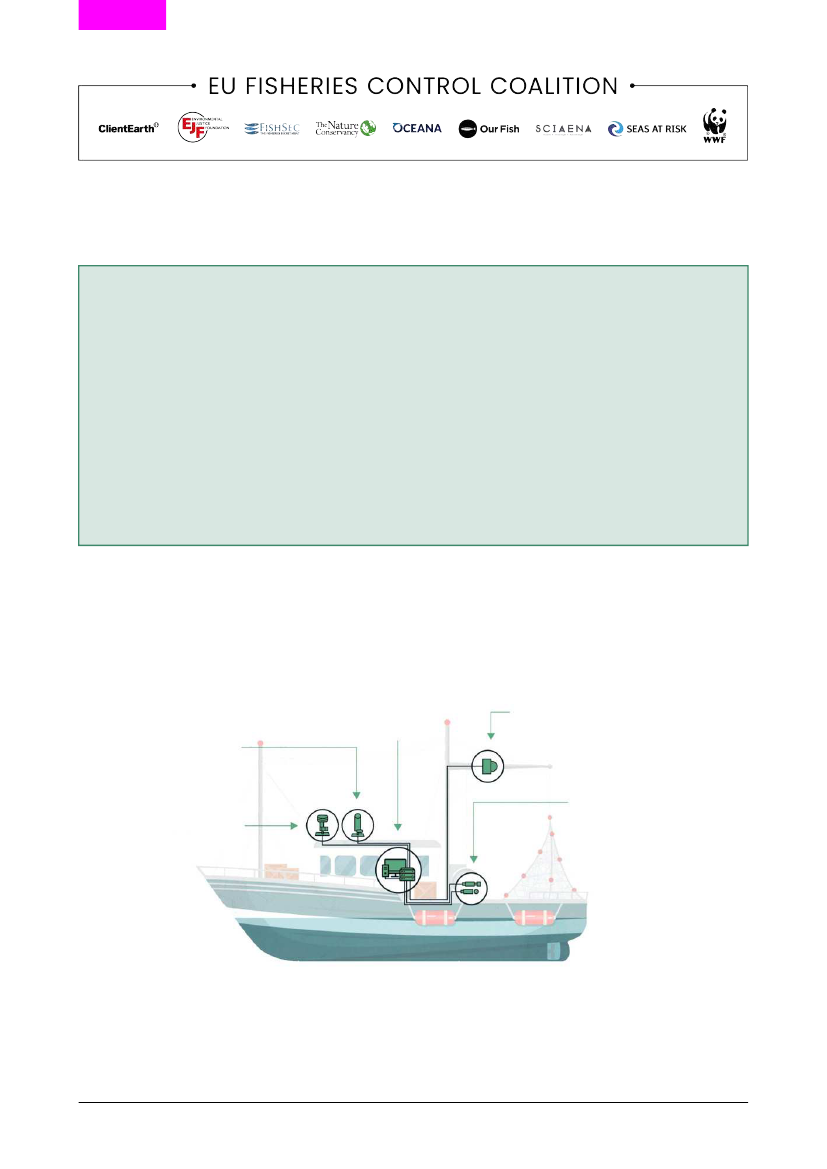

Remote Electronic Monitoring with cameras (REM) does a good job of describing itself. A combination of

cameras and sensors fitted onboard fishing vessels to collect large amounts of independent information on

everything that is caught - including marine wildlife that might not be the main target.

REM Control Centre:

Monitors

Satellite modem:

Reports system

status with

hourly updates

sensors, records data and

displays system summary

Video cameras:

Records

fishing activity from

multiple views

GPS reciever:

Tracks vessel route

and pinpoints

fishing times and

locations

gear usage to

indicate fishing

activity

Hydraulic and

drum-rotation

sensors:

Monitor

Source: Marine Conservation Society UK

Having access to up-to-date and reliable catch data allows managers to confirm that vessels are following

the rules, but can also inform the delivery of stock assessments, catch quotas, and policy decisions that

successfully encourage ecosystem recovery and sustainable practices within the EU fleet. Moreover, it

creates opportunities for fishers to improve their practices and add value to their catch by showing supply

chain partners that they operate legally and sustainably.

1